Intelligent Machines

And the award for most nauseating self-driving car goes to …

I rode in a bunch of autonomous cars so you don’t have to.

In many ways this year’s CES looked a lot more like an autonomous-car show than a consumer electronics show.

There were announcements aplenty from the likes of Ford, Baidu, Toyota, and others about self-driving vehicles, upcoming driving tests, and new partners. In a parking lot across from the Las Vegas Convention Center, several companies offered rides; you could even schedule a ride in a self-driving Lyft through the company’s app and get dropped off at one of many casinos on the Strip.

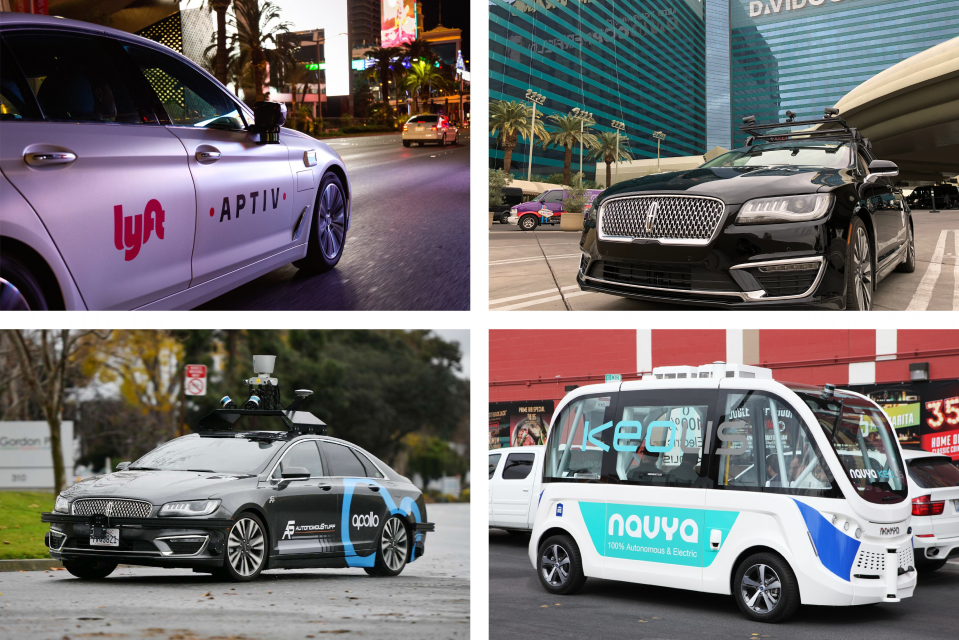

A couple of miles away in downtown Las Vegas, an eight-passenger autonomous shuttle bus ran in a loop around Fremont Street. It was part of an ongoing test between commuter transit company Keolis, autonomous-car maker Navya, and the city.

While there’s still a long way to go before most of us will be able to, say, summon a robo-taxi to go out to dinner, I wanted to get a sense for what it’s like to ride in these vehicles. So over the last week I lined up as many autonomous-car trips as I could and paid attention to things like how smooth the rides were, how the cars reacted to sudden obstacles, and what the overall experience was like to be a passenger in a car with no human hands on the wheel (if there even is a wheel).

The results? Often boring—which in this case is a really good thing—with a side of nausea and a dash of fear.

Most Nauseating

I left the Strip for Fremont Street to take a ride in the autonomous shuttle bus that Keolis and Navya teamed up on—a good opportunity, I figured, to be with other consumers who were also just getting familiar with the technology.

The shuttle, which started operating on a roughly half-mile loop here in November, has a neat design. There is no driver’s seat or designated front or back; instead, there are two parallel benches with four seats apiece, facing each other, and an operator stands up on one side with access to a touch screen and a gaming joystick (no steering wheel or pedals in this thing).

Neither the cool look of the shuttle nor the fact that the first stop was a doughnut shop could offset how sick sitting in it made me feel. Many times it stopped short on the road, even when there was nothing in front of it—our shuttle operator explained that its lidar sensors were probably responding to the closeness of a number of orange traffic cones (which appeared to have been placed to indicate the route the vehicle would take). Caution is great, but its jerky stop-and-start movements made me want to hurl.

Most Nail-Biting

Though it wasn’t technically a self-driving ride, the car from Phantom Auto did glide over to me with nobody inside—while I was standing curbside at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, the car’s operator was in Mountain View, California.

Phantom Auto is developing technology meant to help autonomous cars in situations where they need intervention from a trained human. Though this could one day be really helpful, today it’s actually kind of scary. The operator, who was limited to 25 miles per hour, navigated the car through rain and packed streets at night, taking me and three Phantom Auto employees through a gas station and a couple of other obstacles that are difficult for self-driving cars. Though we got through it all unscathed, the driver’s hesitance was palpable, both while moving across lanes of traffic and while waiting to enter them.

Most Like a Normal Driver

Had I not been paying attention, I could have mistaken my ride in a self-driving Lyft for a regular trip with a good defensive driver.

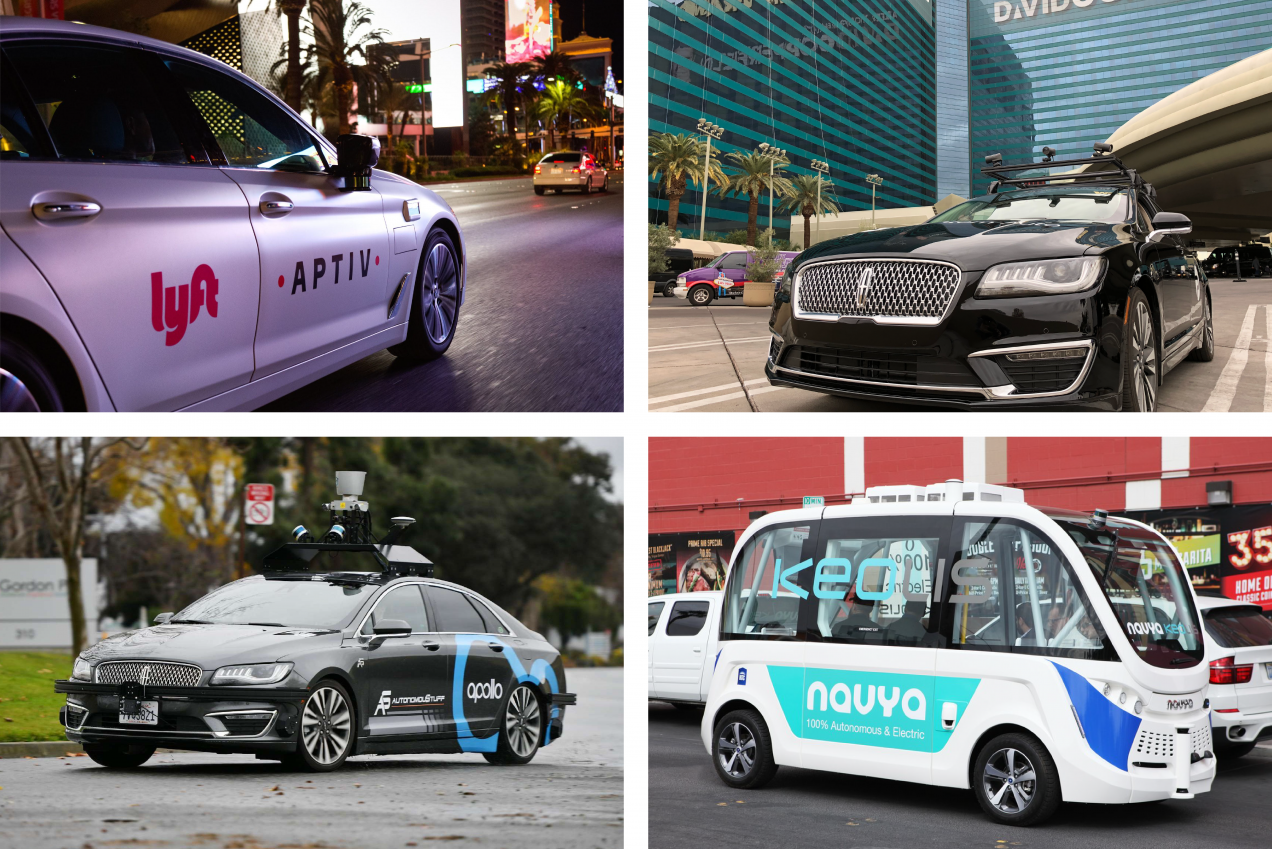

The car, an autonomous BMW 540i that is part of a partnership between Lyft and autonomous-vehicle tech company Aptiv, felt reasonably aggressive as it changed lanes and moved through traffic, speeding up as it went into turns. Yet it was also smart, decelerating appropriately (and not with a lurch) to let pedestrians go through a crosswalk.

I also appreciated the car’s clarity about what was happening during the ride. A touch-screen display showed a simple map of where we were going, and when the car took over on the street (after our human operator drove us out of the parking lot), a female voice piped up, “Autonomous driving!” These are small touches, but they could be key to making passengers feel comfortable as computers take control of the ride.

Most Conservative

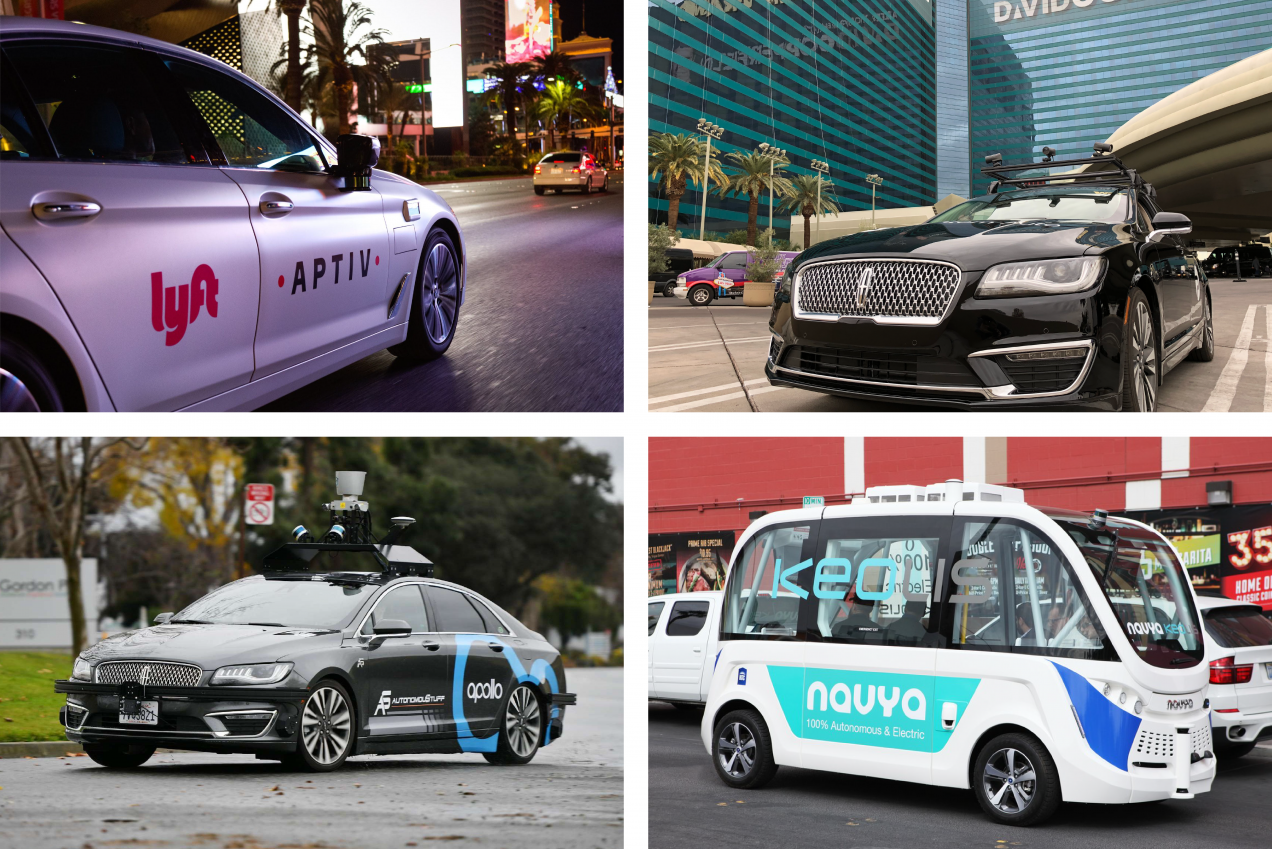

Right before CES, I traveled to Sunnyvale, California, to take a nighttime ride in Baidu’s self-driving car, a Lincoln MKZ hybrid running the latest version of its open-source Apollo software. This ride felt the most cautious—the car carefully sped up as the speed limit increased from 25 to 35 miles per hour, and slowed down very gradually as we approached stop signs and lights.

I do wonder how well the car would do in an aggressive, high-traffic situation, as the streets we drove were quiet and relatively obstacle free. The most startling thing the car did was take a turn wide at a yield sign, making me nervous we’d hit the triangle-shaped median as we merged onto a new street, but my fear was unfounded: it languidly finished the turn and entered the lane.