Humans and Technology

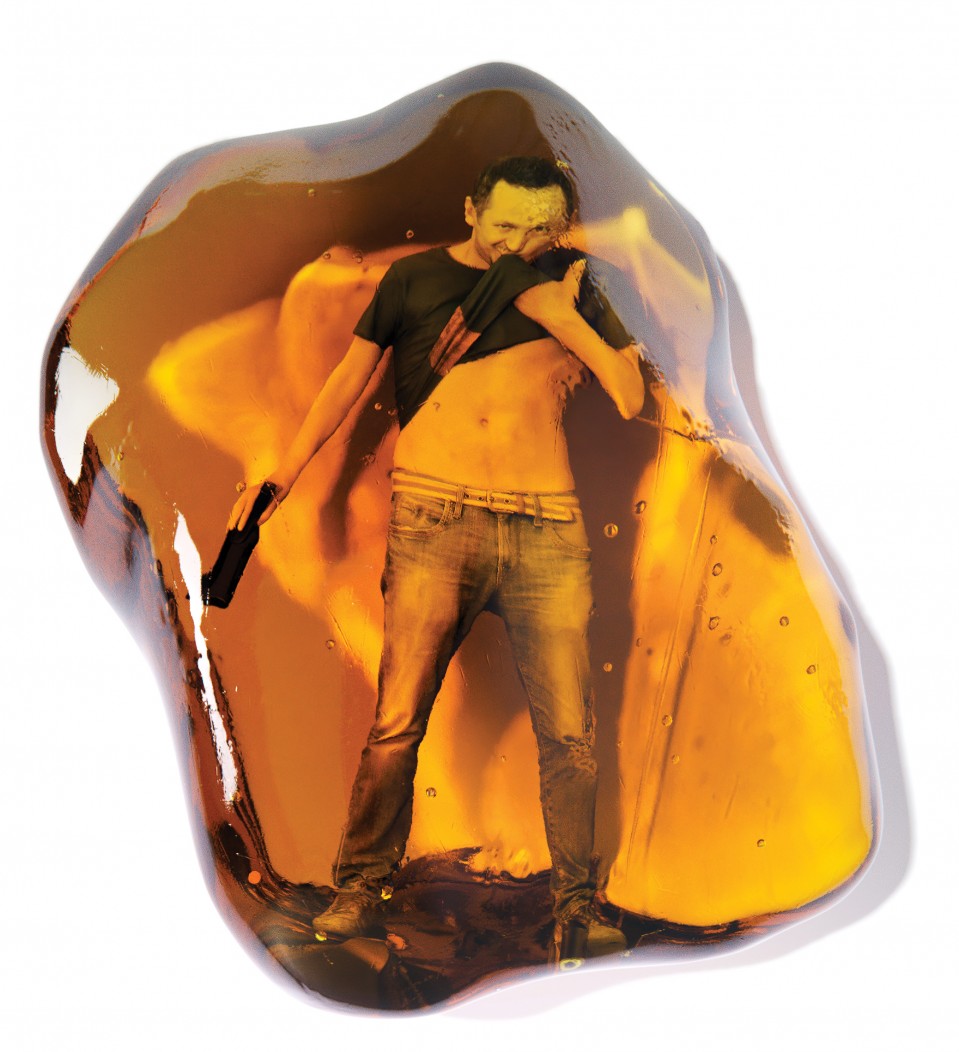

Why an internet that never forgets is especially bad for young people

As past identities become stickier for those entering adulthood, it’s not just individuals who will suffer. Society will too.

Until the end of the 20th century, most young people could take one thing for granted: their embarrassing behavior would eventually be forgotten. It might be a bad haircut, or it might be getting drunk and throwing up at a party, but in an analog era, even if the faux pas were documented in a photograph, the likelihood of its being reproduced and widely circulated for years was minimal. The same held true for stupid or offensive remarks. Once you went off to college, there was no reason to assume that embarrassing moments from your high school years would ever resurface.

Not anymore. Today, people enter adulthood with much of their childhood and adolescence still up for scrutiny. But as past identities and mistakes become stickier, it’s not just individuals who might suffer. Something much larger—the potential for social change and transformation—may also be at risk.

In 2015, the New York Times reported that people around the world were taking 1 trillion photographs each year. Young people take a disproportionate number of them. Some of the teens and tweens I’ve interviewed in my research have told me they capture more than 300 images each day, from selfies to carefully posed photographs of friends to screenshots of FaceTime calls. About a billion photographs a day are uploaded to Facebook alone.

This incessant documentation did not begin with digital natives themselves. Their parents and grandparents, the first users of photo-sharing services like Flickr, put these young people’s earliest moments online. Without Flickr users’ permission or knowledge, hundreds of thousands of images uploaded to the site were eventually sucked into other databases, including MegaFace—a massive data set used for training face recognition systems. As a result, many of these photographs are now available to audiences for which they were never intended.

Meanwhile, digital natives are also the most intensively tracked generation at school. Millions of young people now attend schools where online learning tools monitor their progress on basic math and reading skills alongside their daily social interactions. The tools capture once ephemeral steps in students’ learning and social development.

Other software, like Bark and Gaggle, is used for security purposes, monitoring everything from students’ text messages, emails, and social-media posts to their viewing habits on YouTube by scanning for trigger phrases such as “kill myself” and “shoot.” Someone who messages a friend to say “I nearly killed myself laughing in class today” could be hauled in and asked questions about suicidal thoughts.

Digital school security companies typically delete student data after 30 days, but schools and school districts are free to keep it for much longer. The data is also frequently shared with law enforcement when potential threats are identified. It is unclear what data is being collected by security or learning software, and for how long it is kept. As three US senators wrote in a recent letter to more than 50 educational technology companies and data brokers, “Students have little control over how their data is being used …[they] are often unaware of the amount and type of data being collected about them and who may have access to it.” After all, without any clear checks and balances, one’s bad grades or an intemperate message from middle school could be sold to a job recruitment agency years later (see “Does keeping kids offline breach their human rights?”).

In such a world, tweens and teens who put a foot wrong have a lot to lose.

Consider, for example, the young woman known on Twitter as @NaomiH. In August 2018, excited by news that she had scored a coveted internship at NASA, Naomi went online and tweeted, “EVERYONE SHUT THE F— UP. I GOT ACCEPTED FOR A NASA INTERNSHIP.” When a friend retweeted the post using the NASA hashtag, a former NASA engineer discovered it and commented on Naomi’s vulgar language. NASA eventually canceled her internship.

Or take @Cellla, who in 2015 was about to start a far less glamorous position at Jet’s Pizza in Mainsfield, Texas. “Ew I start this [expletive] job tomorrow,” she tweeted. When the restaurant owner saw the tweet, he replied, “No you don’t start that job today! I just fired you! Good luck with your no money, no job life!” His implication was clear—with a single tweet, Cellla had lost not just this job, but possibly future ones.

Other teens have paid a price for less obvious offenses. In 2016, the principal of Cañon City High School in Colorado disciplined a student for tweeting, “The concert choir and all their makeup is the only clowns we got around here.” He also disciplined 12 classmates for simply liking the tweet. In 2018, a senior at Sierra High in Tollhouse, California, shared a post of Snoop Dogg holding what appeared to be a marijuana joint. She was suspended for “engaging in inappropriate sexual and drug propaganda.”

Maybe these posts are indeed bad form. But isn’t this precisely the sort of inane behavior expected of teens? And if teens can’t be a bit outrageous and make stupid mistakes, what’s at stake? Are we losing that elusive period between childhood and adulthood—a time that has, at least for the past century, been set aside for people to explore, take risks, and even fail without significant consequences?

Erik Erikson, a 20th-century psychoanalyst best known for his theorizing on identity development, suggested in his 1950 book Childhood and Society that the adolescent mind is in “a psychosocial stage between childhood and adulthood, and between the morality learned by the child, and the ethics to be developed by the adult.” During this period, the adolescent can enjoy a “psychosocial moratorium”—not on experience, but rather on the consequences of decisions.

Not all young people have consistently been granted this moratorium on consequences. Indeed, youth incarceration rates in the United States suggest that the opposite may hold true for some—particularly for young men from Latino and African-American backgrounds. Still, in most communities, most people agree that children and teens should be able to make mistakes from time to time and have those mistakes both forgotten and forgiven. This is precisely why most jurisdictions treat young offenders differently from adults.

But for digital natives, the constant recording of even their most minor mistakes and embarrassments means that this long-standing agreement now appears to be threatened. And this isn’t bad news only for them, but for society at large.

My research on youth and media practices indicates that as young people lose their ability to explore new ideas and identities and mess up without consequence, there are two critical dangers.

First, some are already becoming so risk-averse that they may be missing out on at least some of the experimentation that has long defined adolescence. While people like NaomiH and Cellla get into the news for their indiscretions, what’s less visible is how carefully many digital natives now curate their online identities, taking their cues more from CEOs than from their reckless peers.

LinkedIn originally had an age minimum of 18. By 2013, the professional networking site had lowered its age floor to 13 in some regions and 14 in the United States, before standardizing it at 16 in 2018. The company wouldn’t say how many middle and high schoolers are on the platform. But they aren’t hard to find.

As one 15-year-old LinkedIn user (who asked to remain anonymous for fear of losing her account) explained to me, “I got my first LinkedIn page at 13. It was easy—I just lied. I knew I needed LinkedIn because it ranks high on Google. This way, people see my professional side first.” When I asked why she needed to manage her “professional side” at 13, she explained that there’s competition to get into high schools in her region. Since starting her LinkedIn profile in eighth grade, she has added new positions and accomplishments—for example, chief of staff for her student union and chief operating officer for a nonprofit she founded with a 16-year-old peer (who, not surprisingly, is on LinkedIn too).

My research suggests that these users aren’t outliers but part of a growing demographic of tweens and teens who are actively curating their professional identities. But should 13- or 15-year-olds feel compelled to list their after-school activities, academic honors, and test scores on professional networking sites, with photos of themselves decked out in corporate attire? And will college admissions officers and job recruiters start to dig even further back when assessing applicants—perhaps as far back as middle school? The risk is that this will produce generations of increasingly cautious individuals—people too worried about what others might find or think to ever engage in productive risks or innovative thinking.

The second potential danger is more troubling: in a world where the past haunts the present, young people may calcify their identities, perspectives, and political positions at an increasingly young age.

In 2017, Harvard University rescinded admission offers to 10 students after discovering that they had shared offensive memes in a private Facebook chat. In 2019, the university withdrew another offer—to Kyle Kashuv, an outspoken conservative survivor of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. In Kashuv’s case, it wasn’t a social-media post that caused the trouble, and it wasn’t an adult who exposed him. Back in 10th grade, Kashuv had repeatedly used the N-word in a shared Google document created for a class assignment. When Harvard accepted him, his peers recovered the document and shared it with the media.

There are reasons to applaud Harvard for refusing to take these students. Such decisions offer hope that future generations will be held accountable for racist, sexist, and homophobic behavior. This is a step in the right direction. But there is a flip side.

When Kashuv discovered he had lost his place at Harvard, he did what any digital native would do—he shared his reaction online. On Twitter, he wrote, “Throughout its history, Harvard’s faculty has included slave owners, segregationists, bigots and antisemites. If Harvard is suggesting that growth isn’t possible and that our past defines our future, then Harvard is an inherently racist institution.”

His argument may be a poor excuse for his actions, but it raises a question we can’t afford to ignore: Should one’s past define one’s future? The risk is that young people who hold extreme views as teenagers may feel there’s no use changing their minds if a negative perception of them sticks regardless. Simply put, in the future, geeky kids remain geeky, dumb jocks remain dumb, and bigots remain bigots. Identities and political perspectives will be hardened in place, not because people are resistant to change but because they won’t be allowed to shed their past. In a world where partisan politics and extremism continue to gain ground, this may be the most dangerous consequence of coming of age in an era when one has nothing left to hide.

Kate Eichhorn’s most recent book is The End of Forgetting.