Filters less foul

A new imaging technique could lead to better membranes.

Oil and water are famously reluctant to mix fully together. But separating them completely—for example, when cleaning up after an oil spill or purifying water contaminated through fracking—is a devilishly hard and inefficient process frequently dependent on membranes that tend to get clogged up, or “fouled.”

A new imaging technique, developed by MIT graduate students Yi-Min Lin and Chen Song and professor of chemical engineering Gregory Rutledge and described in the journal Applied Materials and Interfaces, could provide a tool for developing better membrane materials that can resist or prevent fouling.

The fouling process is very hard to observe, making it difficult to assess the relative advantages of different membrane materials and architectures. The new technique could make such evaluations much easier to carry out, the researchers say.

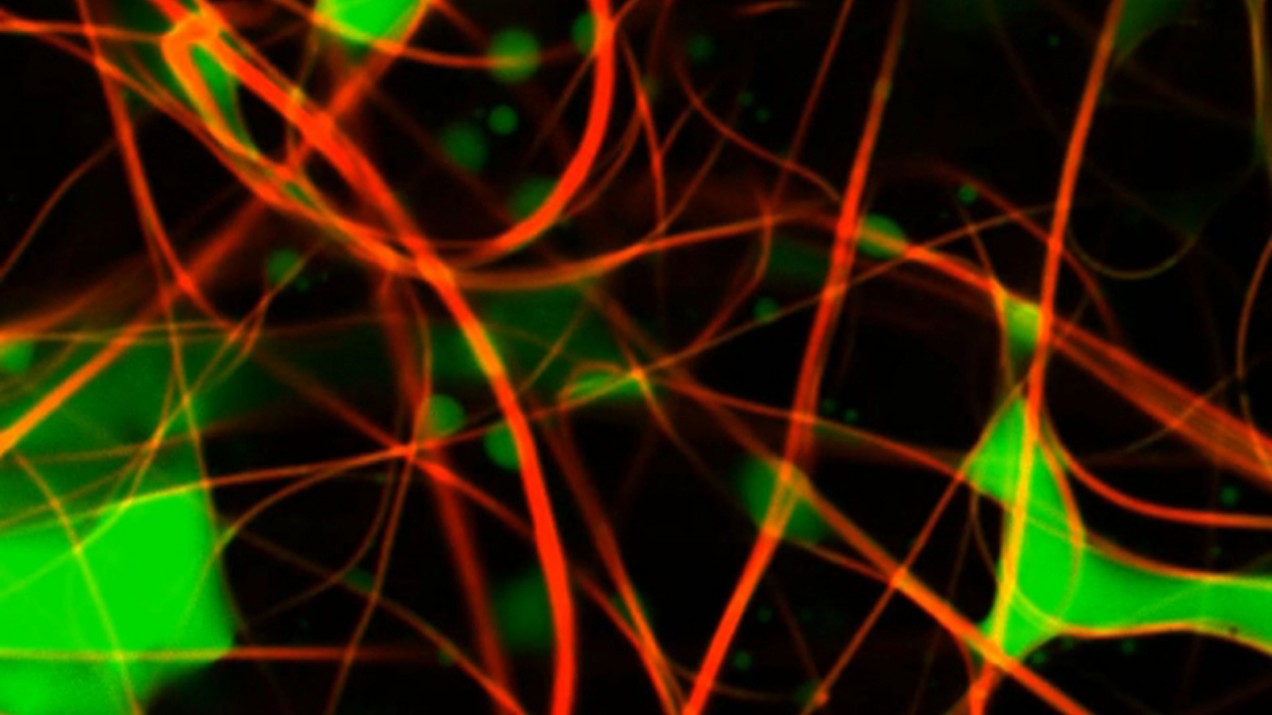

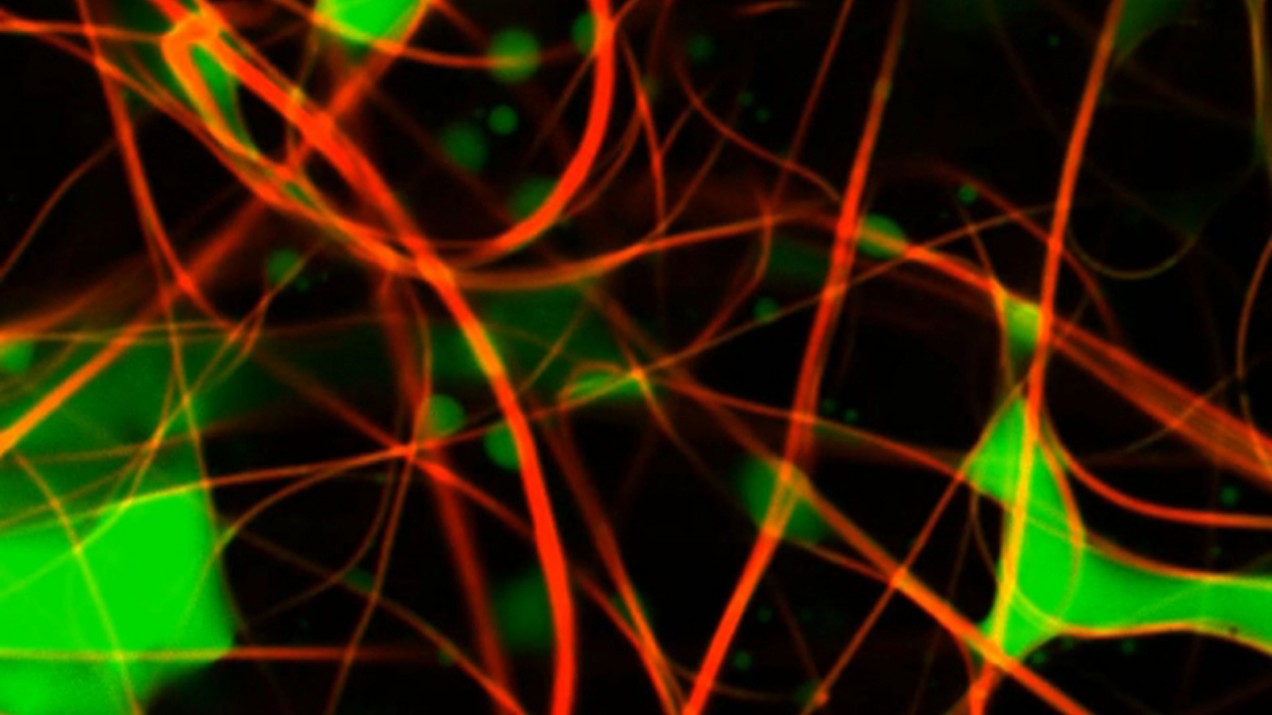

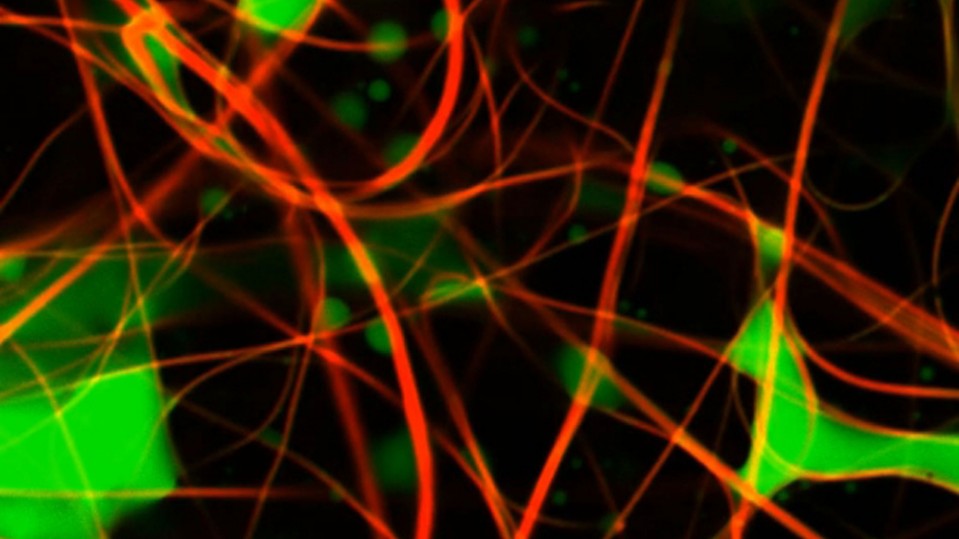

Using two dyes that fluoresce at different wavelengths, the researchers labeled the fibers of the membrane with one and the oily material in the fluid with the other. Then, employing confocal laser scanning microscopy, they used two lasers—one to illuminate each dye—and controlled the position and depth of the lasers’ focus to collect stacks of 2D images at different depths. Their technique can build up a full 3D image showing the oil, fiber, or both, making it possible to see how the oil droplets are dispersed in the membrane.

Doing so, and testing the effects using different materials and different arrangements of the fibers, “should give us a better understanding of what fouling really is,” Rutledge says.