Holed up in a cramped room of her house, Tamitha Skov gets set in front of a makeshift green screen, which has been cobbled together from two green bed sheets. She cues up a script on her computer and hits Record.

Staring down the lens, she says, “We finally quieted down from multiple solar storms that brought us aurora pretty much all over the world last week, and the two regions responsible have rotated to the sun’s backside. What does that mean for you? Those stories and more in the news this week.”

Skov could be one of the thousands of on-air weather forecasters who take to the airwaves each day. But instead of sharing rainfall and temperature forecasts, Skov—a.k.a. the Space Weather Woman—is one of the few who explain space weather.

Hers is a relatively new field. She details things like solar wind, solar flares, geomagnetic storms, and coronal mass ejections—streams of charged particles and magnetic fields that originate in our star’s outer atmosphere.

Courtesy of Tamitha Skov

Space weather can create spectacular auroras. But it can also disrupt and disable satellites that provide services like GPS. It can affect electrical grids, or even threaten astronauts onboard the International Space Station with dangerous levels of radiation.

A number of centers around the globe, like the Space Weather Prediction Center in Colorado, are set up to measure and predict these storms. Using both space-based and ground tools, researchers take pictures and measurements of the sun, and warn governments and companies when dangerous space weather might be approaching. A government, for example, might then respond by shutting down satellites or electrical grids.

Such reports are dense, so Skov simplifies them for non-experts—a task she’s been doing for five years, uploading the reports to her YouTube channel. Her viewers include groups that rely heavily on satellites, or people who need to know about natural events that arise from space weather—farmers, for example, or members of the US military, aurora photographers, pilots, drone operators, meteorologists, ham radio operators.

“When you get into ham radio, it’s all about the ionosphere,” says Keith Gordon, a pilot, a longtime ham radio enthusiast, and one of Skov’s weekly viewers. “Why can I reach halfway across the world some days, and I can’t get more than 50 miles away other days? Well, our magnetosphere is a living, breathing thing, and it’s driven by the sun.”

Though these small communities follow her work religiously, Skov wants to break space weather out of its niche. “My ultimate goal is to create the field of space weather broadcasting so that it’s on the nightly news, right alongside your terrestrial weather,” she says.

Watching the weather

For most of us, paying attention to space weather is about preparation. Just as you’d want advance warning of when your power or internet might go out because of a hurricane, you’d probably want to know when a solar storm might have the same effect. The people of Quebec didn’t get that warning in 1989, when a geomagnetic storm caused a 12-hour citywide blackout. Neither did the residents of Malm, Sweden, in 2003.

Related story

The space mission to buy us vital extra hours before a solar storm strikes

The sun’s violent activity can shut down the power grid and knock out satellites. ESA’s Lagrange mission will be our early warning system.

Solar storms can cause airlines to reroute flights away from the poles, where radiation concentrates, so a space weather report could indicate that your flight times might change. If you know a mild storm is on its way, you’ll know in advance that Google Maps or Uber—or any other GPS-dependent service—might be unreliable for a while.

Knowing the space forecast is especially important if you live near the poles, or in a country like Brazil, which faces frequent disturbances to GPS because of the plasma bubbles that form along the equator, and atmospheric fluctuations that affect radio signals. Brazil has, in fact, partnered with NASA to launch a small satellite known as a cubesat to better understand the phenomenon, with the idea that locals will know when their GPS and communications services are likely to be inoperable.

Skov didn’t plan for or even hope for this career path. She has a PhD in geophysics and space plasma physics, and initially got on Twitter to promote her music career. Instead she got ingrained in a different community—she started using her solar knowledge to answer questions that early users of Twitter had about space weather, and found herself bombarded with specific questions ranging from why agricultural GPS was having trouble connecting to whether space weather was to blame for drone navigation issues. Then she got requests for space-weather forecasts.

Space Weather Woman

Soon she became the go-to person for solar questions. “I began to realize that not only is there a need for this stuff, there’s a specific need in the specific user groups. And the user groups are getting bigger all the time,” says Skov. Her answer to this gap was creating space-weather forecast videos. Her small but dedicated community of 22,000 subscribers and 32,000 Twitter followers has helped her amass nearly a million views on her channel.

Space weather’s devastating potential

There’s a lot we don’t understand about space weather. “We are trying to take terrestrial weather forecasting techniques and use it for space-weather forecasting,” says Sophie Murray, a research fellow at Trinity College Dublin. “We are quite a few decades off from catching up with them.”

"As consumers, we didn't have the technology that will be impacted, but now we do. Now it's ubiquitous."

Tamitha Skov

That gap exists partly because space weather hasn’t mattered much until the past few decades. As a result, we haven’t invested as much into it as we have into meteorology. But with the rise of smartphones and internet constellations, satellites have become an essential part of modern life. “As consumers, we didn’t have the technology that will be impacted, but now we do,” says Skov. “Now it’s ubiquitous.”

Luckily for us, the sun has been pretty calm in recent years as it’s gone through what’s known as solar minimum. We’re now at the relatively peaceful end of the 11-year solar cycle. In the middle of the cycle, the sun’s magnetic poles flip, which typically coincides with more extreme solar activity. That happened in 2014, and there’s been little action since. “There hasn’t been a coronal mass ejection or a flare to draw attention on a public scale,” says Richard Clark, chair of the department of earth sciences at Millersville University in Pennsylvania.

But the sun is capable of much more. The most infamous event in the history of space weather is the Carrington Event. In 1859, a massive solar storm produced so much geomagnetic activity that even people in Cuba could see the Northern Lights. Telegraph operators reported sparks flying from their equipment. “The more technology dependent we become, the more sensitive we will be to even moderate to severe storms,” says Michael Cook, space-weather forecaster lead at Apogee Engineering, an engineering contractor. While something like the Carrington Event might happen every 100 or 200 years, scientists aren’t really sure when a storm of that magnitude could hit again.

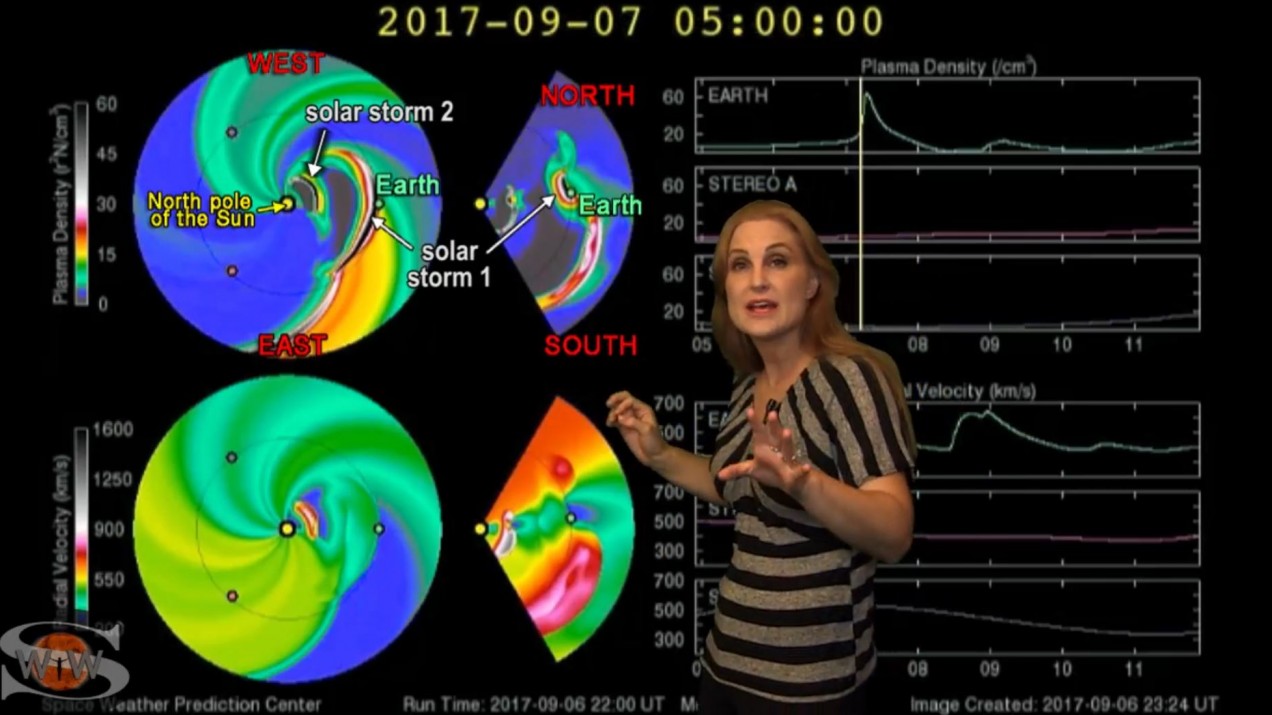

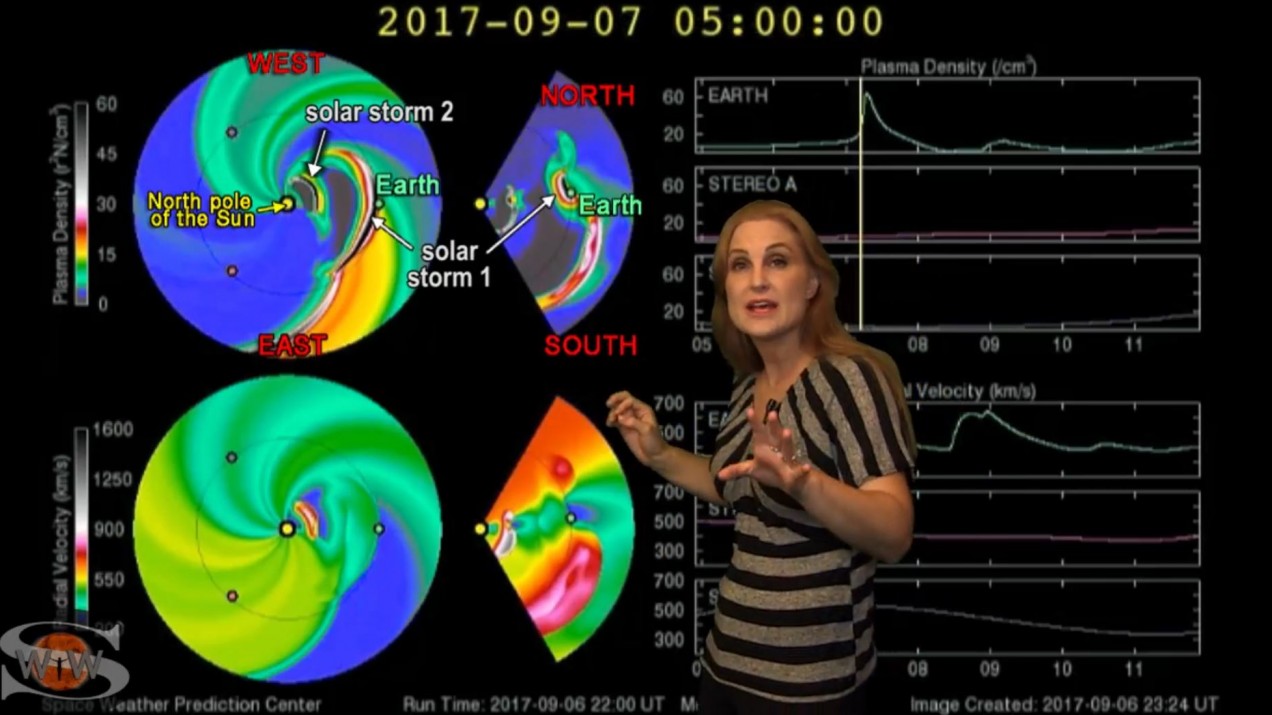

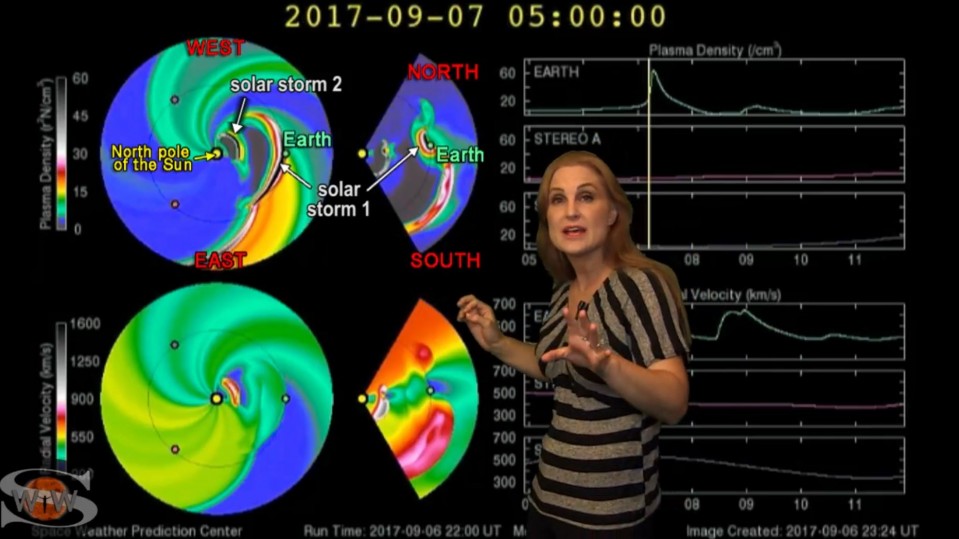

Courtesy of Tamitha Skov

In 2017, we got a small taste of what space weather can do. As hurricanes slammed into the Caribbean, emergency radio communications went down. Many thought the hurricanes were disrupting the satellites, but instead it was the sun.

“There was a huge, ugly sun spot that was firing off basically the biggest flares of the entire solar cycle, and big gigantic storms,” says Skov. “It was killing the satellite phones. It was killing amateur radio.”

Join the space gang

Skov faces a constant influx of media requests and questions from people wanting to know what’s messing up their GPS. She does everything from speaking on international panels to performing parody covers of “Here Comes the Sun” on her ukulele at the Dayton Hamvention, a convention for ham radio enthusiasts.

Balancing this along with her job at Aerospace Corporation (where she works one day a week) has been a struggle, especially given some medical issues with close family members. “It’s so overwhelmed me this year. I realized that if I don’t slow down, it's going to permanently take the fun out of this,” Skov says. “I don’t want to do that because I think that there’s a huge need. And I’m still just beginning to figure out what that need is.”

Skov knows she can’t do it on her own, so she’s building the pipeline to create a new network of space-weather broadcasters. Starting this winter, Space Weather and Environment: Science, Policy, and Communication, a graduate certificate program she helped design in conjunction with Cook and Millersville University, will be open for sign-ups. It’ll cover the basics of space weather, how it affects the modern world, and how best to share information about it. It’s designed for people working in fields affected by space weather, as well as on-air meteorologists.

Courtesy of Tamitha Skov

Both Skov and Cook, of Apogee Engineering, believe local weather reporters are the perfect people to disseminate space-weather information. “Space weather in Minnesota is not even close to the space weather in Florida,” Skov says. “We’re going to have to have local space-weather people doing local space weather from these regions.”

"This is space, and it's affecting you."

Tamitha Skov

Kerrin Jeromin, the director of weather operations at WeatherNation, has already sought out some basic online space weather training. “Often, as the only scientist at a television station, you are called upon to talk about various scientific topics outside of terrestrial weather, and must present that information to the public audience in an easy to understand way,” she says.

Greater public awareness of the field will do more than just prepare us for solar storms. Skov believes it should also help us better understand our connection to space. “This is space,” she says, “and it’s affecting you.”

Advertisement