Bacteria help lung tumors grow

An immune response creates a hospitable environment for cancer.

MIT biologists have discovered a new mechanism that lung tumors exploit to promote their own survival: they alter the lung’s bacterial populations, provoking the immune system to create an inflammatory environment that helps tumor cells thrive.

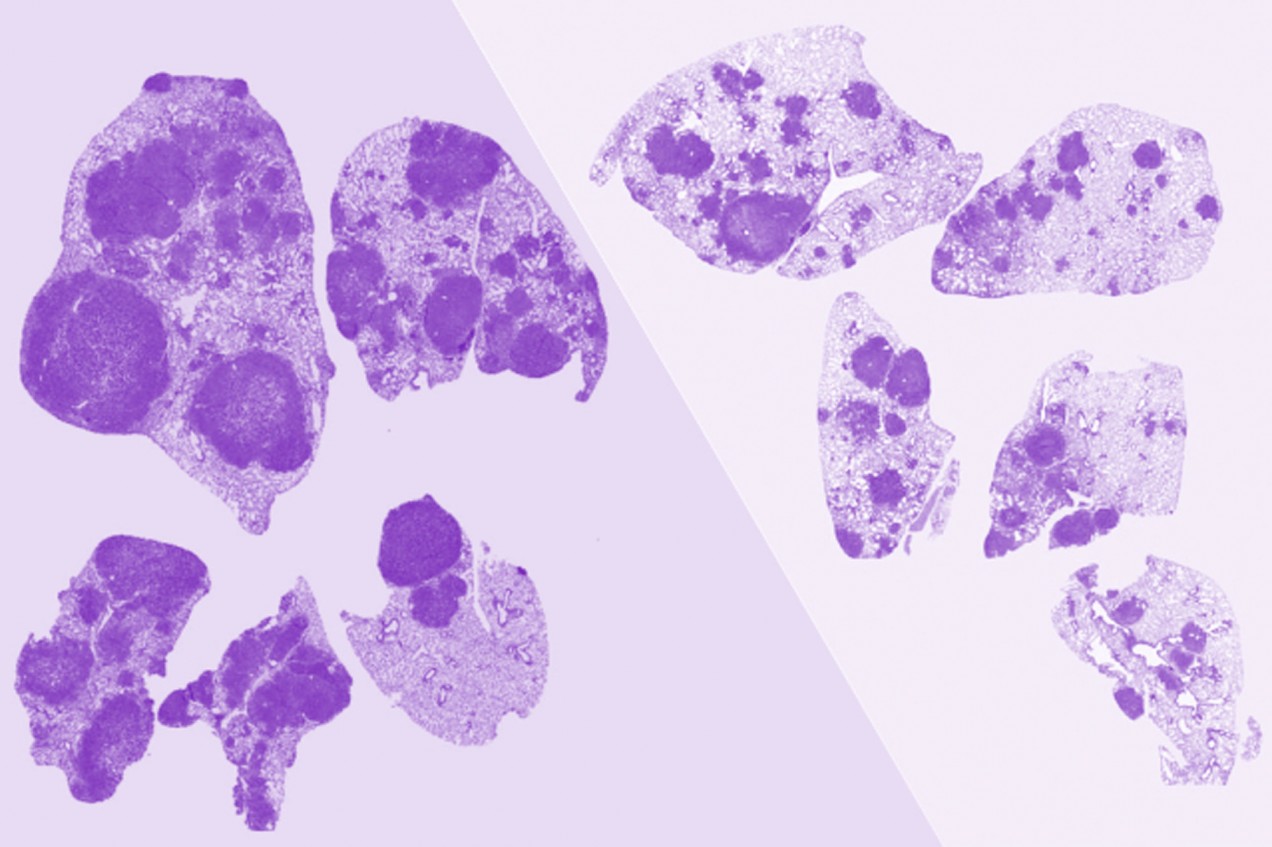

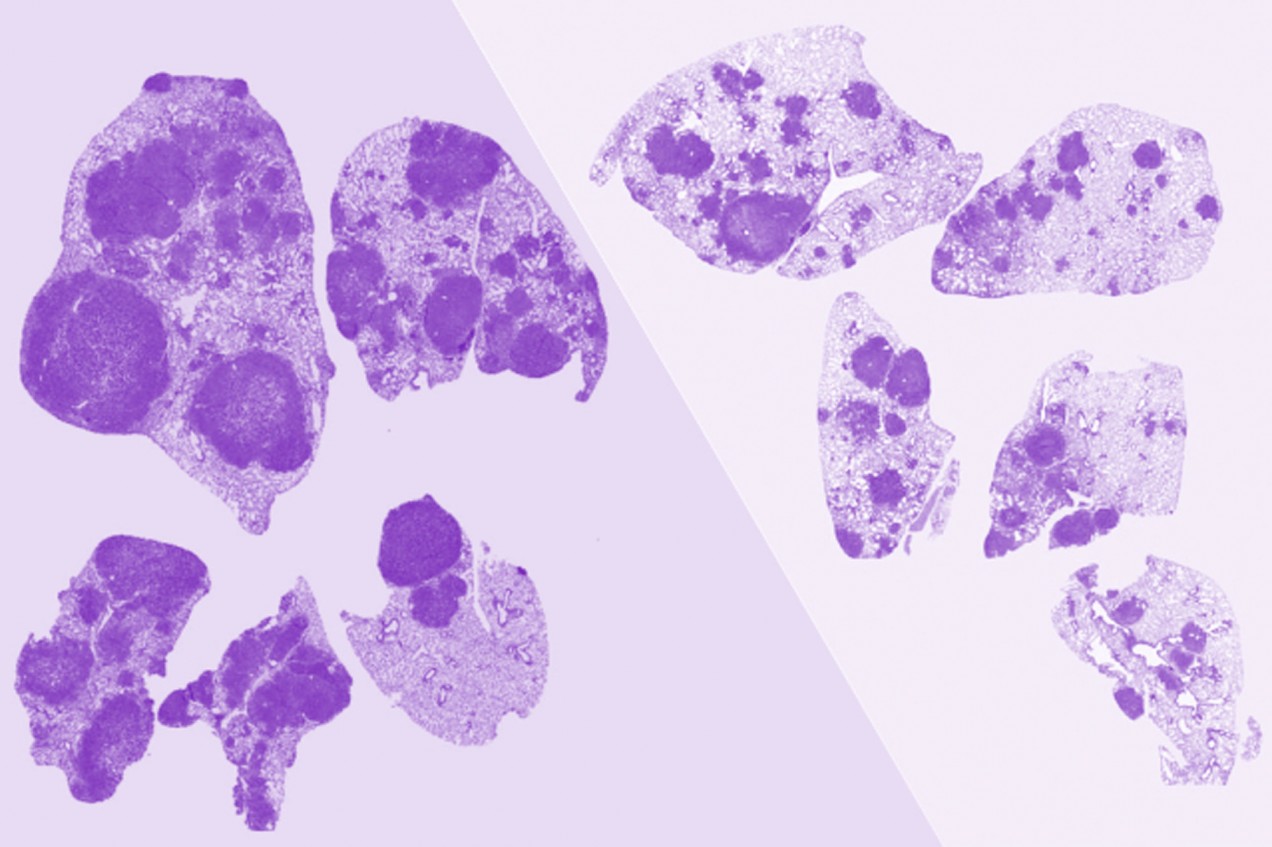

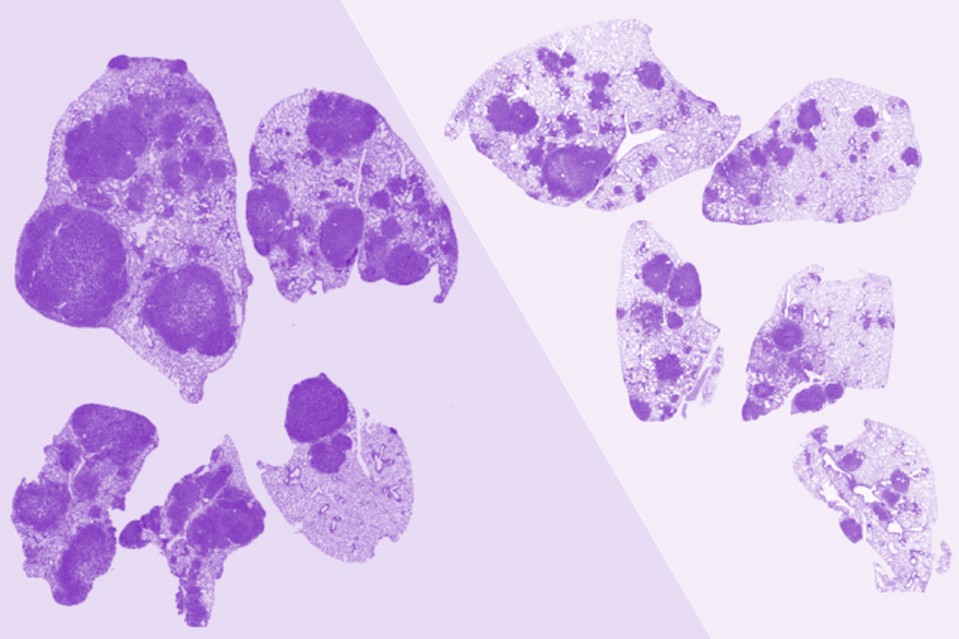

In mice genetically programmed to develop lung cancer, those raised in a bacteria--free environment developed much smaller tumors than mice raised under normal conditions. And treating the latter mice with antibiotics resulted in tumors that were about 50% smaller. Giving them drugs that blocked the immune response also significantly inhibited tumor development.

“This research directly links bacterial burden in the lung to lung cancer development and opens up multiple potential avenues toward lung cancer interception and treatment,” says Tyler Jacks, director of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and senior author of a paper on the work published in Cell; postdoc Chengcheng Jin was lead author.

Lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer--related deaths, kills more than 1 million people worldwide per year. Up to 70% of patients also suffer complications from bacterial infections of the lung.

Mice (and humans) typically have many harmless bacteria in their lungs. The mice engineered to develop lung tumors harbored fewer bacterial species, but their lungs’ overall bacterial population grew significantly. That caused immune cells called gamma delta T cells to proliferate and begin secreting cytokines, inflammatory molecules that promote tumor growth.

The researchers’ analysis of human lung tumors revealed unusually high numbers of gamma delta T cells and altered bacterial signals similar to those seen in the mice, so they believe drug treatments like those that inhibited mouse tumor development are worth testing in humans.