Climate Change

The “mind-boggling” task of protecting New York City from rising seas

There are plans to fortify the city’s 520 miles of coast—but some of them will be unpopular.

Until a few years ago, Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park in Long Island City, Queens, was an industrial landfill. Now it’s a modern-day version of the marshes that once flanked the East River, with a running path that zigzags along the water’s edge atop a grassy berm, and an inlet filled with marsh grasses to let water flow in and out with the tides.

The park, completed in 2017, is also a fortification. The marshland is designed to absorb flooding from storms and sea-level rise, while hills, berms, and concrete walls block or redirect floodwaters to protect the neighborhood.

Nearly seven years ago, the swollen river flooded Long Island City during Superstorm Sandy, pouring through streets and damaging cars and basements. (It also killed more than 40 people across New York City.) But that hasn’t turned people away from the water.

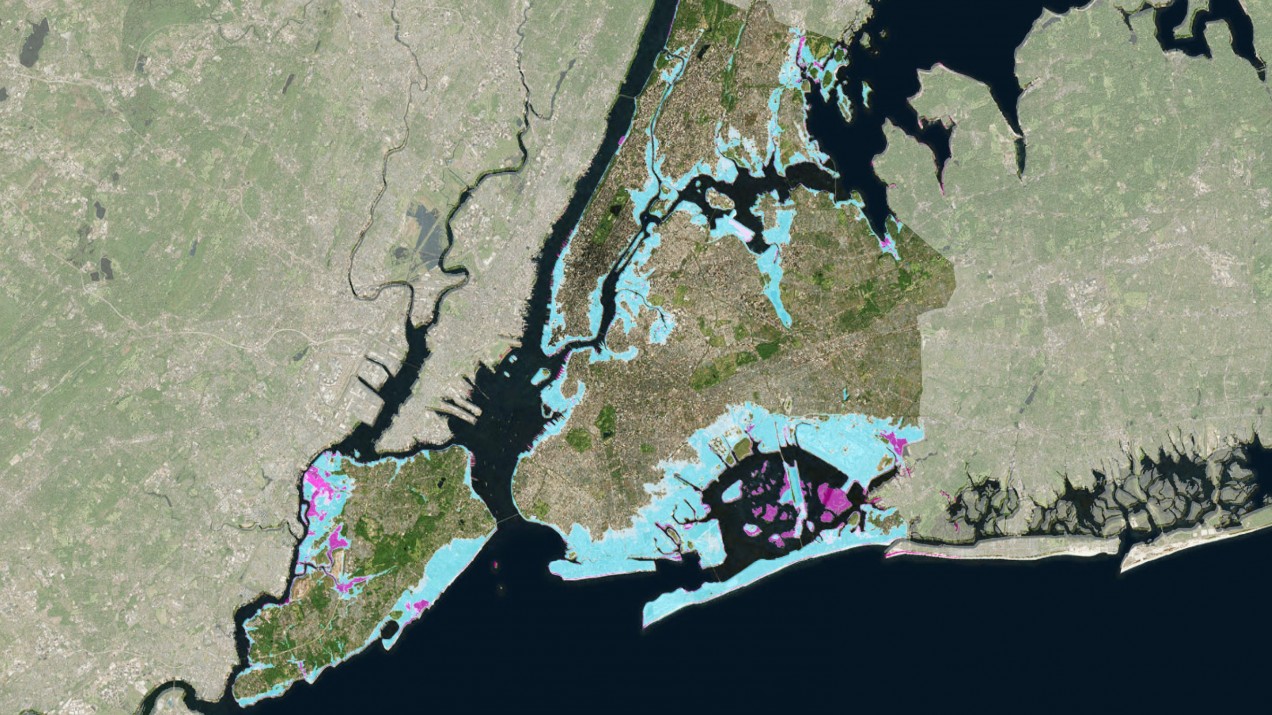

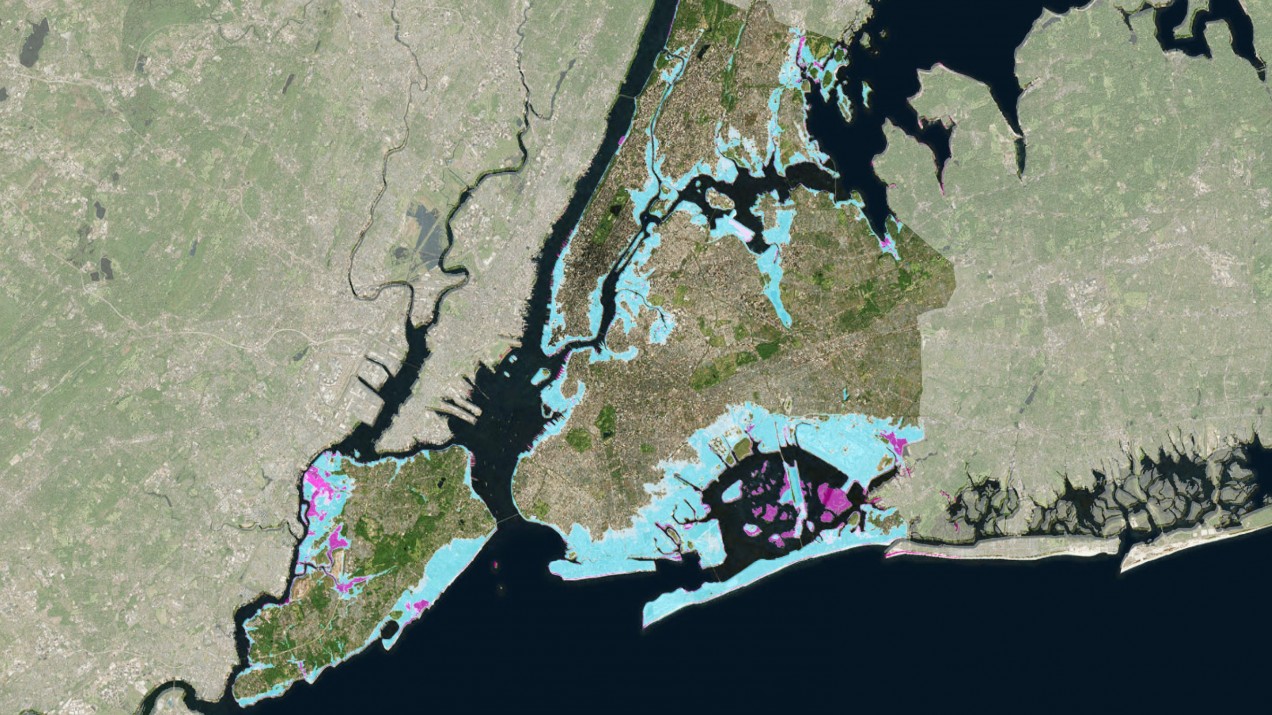

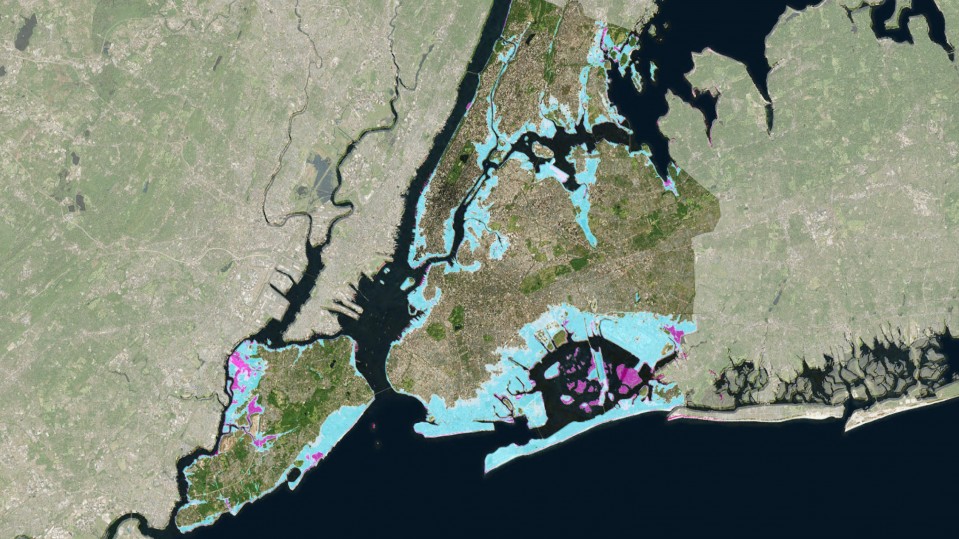

As the climate warms, the city will have to reconfigure much of its urban fabric, particularly the 520 miles (837 kilometers) of shoreline. “It’s a mind-boggling scale,” says Ellis Calvin, a planner and data research manager at the independent nonprofit Regional Plan Association (RPA), as we stand at the water’s edge. By the middle of the century, the New York City Panel on Climate Change estimates, temperatures in the city could be hotter on average by 4 to 6 °F (about 2 to 3 °C), with several heat waves per summer. Sea levels could rise 11 to 21 inches (28 to 53 centimeters) by the 2050s and up to six feet (1.8 meters) by 2100—doubling the size and population of the 100-year-flood zone, the area that has a 1% annual chance of flooding. The borough with the most land affected by all this will be Queens.

New York is ahead of many coastal cities in plans for adapting to climate change. But according to the RPA, an analysis of state disaster resiliency plans in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut by Harvard architecture professor Jesse Keenan suggests that more than $27 billion of planned investments to recover from Sandy have not been made.

Climate resilience is expensive and onerous. Seven projects in the region got federal funding in a post-Sandy design competition called Rebuild by Design, but several years later, not one has broken ground. Last fall, the city abruptly changed plans for the first phase of the “Big U,” a project that would create and connect 10 miles of parks, barriers, and flood walls around the low-lying area from East 57th Street down to the Battery and up West 42nd Street. The city eschewed an innovative approach that would allow a newly redesigned East River Park to partially flood during storms, deciding to spend more money to raise the park 8 to 10 feet, adding fill that may cover natural habitats. Amy Chester, managing director of Rebuild by Design, says that when cities move from concepts to implementation, “a lot of the innovation falls to the side.”

What will New York City look like in a few decades as sea levels rise? The city has an idea—and some thoughts on how to deal with it—in what’s known as the Fourth Regional Plan.

More than 2 million people will be living in areas vulnerable to flooding.

The plan calls for housing buyouts in flood-prone communities like Jamaica Bay, Long Island’s south shore, and the Jersey Shore. It recommends banning new development in these areas immediately, and redirecting funds meant for upkeep toward housing buyouts.

40% of all water treatment plants will be at a high risk of contamination or running dry.

The plan calls for creating a network of water supply systems between Long Island, New York, and New Jersey, affording flexibility in case any one water source is contaminated or destroyed by a storm. The plan suggests this could be paid for by utilities.

New Jersey’s Meadowlands will be underwater.

The Meadowlands—20,000 acres just five miles outside New York City—is home to essential infrastructure like warehouses, commuter and freight rail, and roads into the city. The regional plan calls for phasing out every bit of this infrastructure over time, ceding the land to the water, and making the Meadowlands a national wetlands park that grows over time as sea levels rise.

More than 60% of the city’s power comes from plants that will be at high risk of flooding.

The plan calls for existing power plants to be upgraded, replaced, preserved, or relocated on a case-by-case basis. It suggests flood-proofing facilities when possible by elevating them. It recommends that power plants form a network in case any are knocked out of commission during a severe storm, and calls for increased capacity to cope with the higher demand that will be likely during hot spells.

Subways, railroads, highways, and airports will flood frequently.

Teterboro Airport in Hackensack, New Jersey, handles much of the freight bound for New York City—and it could be under a foot of seawater by midcentury. The plan calls for it to be phased out. Newark and JFK airports should be expanded, the plan says, to handle the extra capacity. Subway systems will become dangerous, given the likelihood of flooding and power outages. The plan recommends creating a government body to modernize the entire subway system—with funding coming from fees on motorists entering the city, among other sources.

Tate Ryan-Mosley contributed research for this story.