Silicon Valley

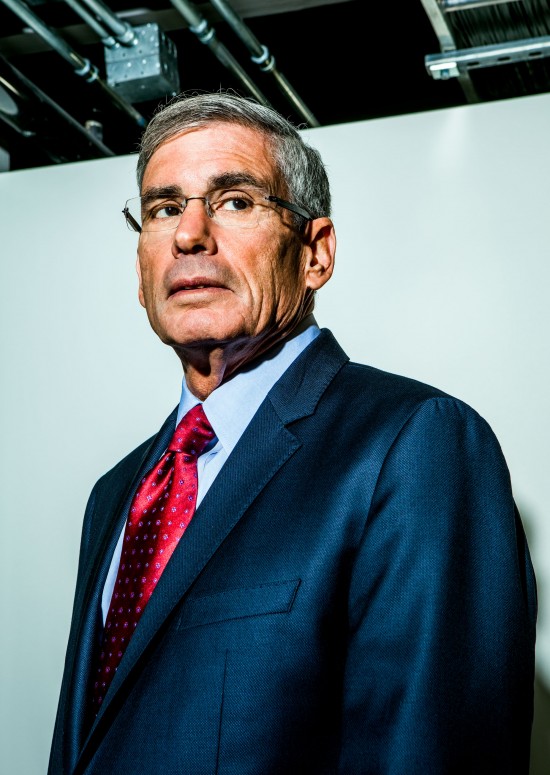

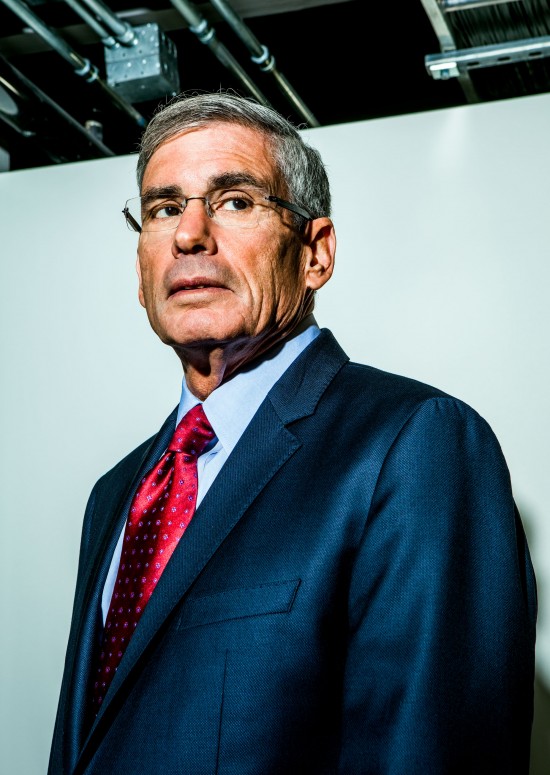

Gary Reback: Technology’s trustbuster

Big-money politics is making it harder than ever to tame Big Tech.

Gary Reback is famous in Silicon Valley as the lawyer who sicced the US Department of Justice on Microsoft. The landmark lawsuit, alleging that the company had abused the dominance of its Windows operating system to favor Internet Explorer over the rival Netscape browser, lasted years and ended in stalemate in 2001; a chastened Microsoft trod more carefully after it. More recently Reback, now with Carr & Ferrell, has been battling Google in Europe, where it was fined 2.4 billion euros ($2.7 billion) last year for suppressing competition in online shopping services. MIT Technology Review’s San Francisco bureau chief, Martin Giles, sat down with him to talk about the challenges trustbusters face in dealing with the latest generation of tech giants.

Doesn't competition constantly produce new winners in the tech industry?

People are wont to say that tech empires naturally come and go, and they cite examples like BlackBerry and MySpace. But the reality of the industry is that it’s always been monopolized. There was AT&T, then IBM, then Microsoft. What we have now are very mature markets, and companies like Google who’ve been at the same market share for years and haven’t faced new competition for some time.

Should the big companies be broken up?

As an antitrust enforcer, you would never want to start there. You’d start with the anticompetitive conduct in question and see if you can remedy that. And if you can, you then check whether that’s sufficient to let the free market support additional competition.

And what if it isn’t?

Historically, whenever we’ve come down hard on a big tech monopoly, it’s worked out great for the American people. When AT&T was broken up, I think you could realistically claim that’s where we got the internet from, and certainly there was a whole wave of innovation, including cell phones and pagers, that was arguably being held back by the monopoly.

Why hasn’t antitrust action affected the large tech companies so far?

The problem is that there’s been no effective remedy [to anticompetitive behavior on the part of tech businesses]. The European case that’s furthest along is the shopping search manipulation case against Google. It’s been fined a massive amount of money, but the remedy hasn’t really restored competition.

What’s the biggest lesson to take from all this?

You’ve got to move fast when anticompetitive conduct starts occurring and stop it quickly. In these kinds of network markets, once competition’s gone, it’s gone. If the EU had done what it did in 2017 in 2007, which is when the conduct began, then we’d have all these companies that started in shopping search trying to compete with Google more generally.

The Microsoft trial dragged on for many years, though.

Yes, but the trial was a key part of the remedy, and you shouldn’t forget that. People at the time thought that Microsoft was great. They didn’t understand what was going on. But when you have this trial, and you put up their e-mails and you cross-examine the CEO, then journalists get interested. It’s all exposed so we can analyze it. You can’t do that right now with Google, because you don’t know all of the things that it is doing with data.

Will we see another landmark trial soon?

I’m not optimistic. Part of the problem here is that all of the big technology companies understand how much damage a trial could cause. They’d do anything to avoid that kind of scenario.

Should we stop them from buying firms?

We should be looking closely at these deals. What in the world were we thinking when we let Facebook buy WhatsApp? And when we let Google, which already had the top mapping technology, buy Waze? One of my greatest complaints is that the Obama administration did not heed the warnings. I was telling people about the risks all the way back to Google’s acquisition of DoubleClick [in 2008].

Why hasn’t the US been tougher on big tech firms?

If you are going up against big tech companies, they have plenty of money. That can be used to contribute to politicians on an unlimited basis, and to hire the best lobbyists, and so on. Why is it that we were able to go after Microsoft in the 1990s, and now we’re facing almost identical conduct by Google and we can’t manage to do anything about it in the US?

So will we have to rely on Europe to police the web giants?

One way you might get change in the US is to have some maverick win the White House who isn’t beholden to the normal party and campaign processes. And that’s kind of what we have at the moment. We’ve seen the Trump administration attack the AT&T–Time Warner merger; I doubt the Obama administration would have done that. But will this lead to enforcing antitrust laws in the technology industry? We just don’t know yet.