Computing / Cybersecurity

Sitting with the cyber-sleuths who track cryptocurrency criminals

Cryptocurrency networks are turning out to be far less private than we thought, and forensic investigators are turning that to their advantage.

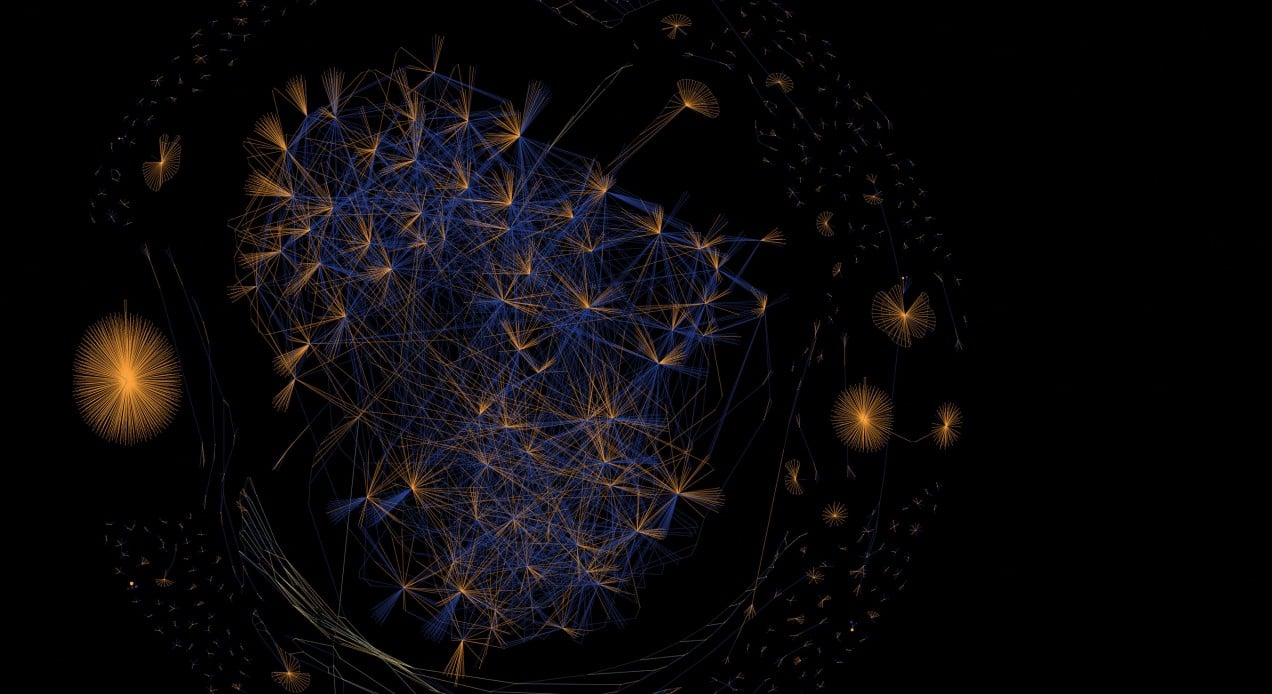

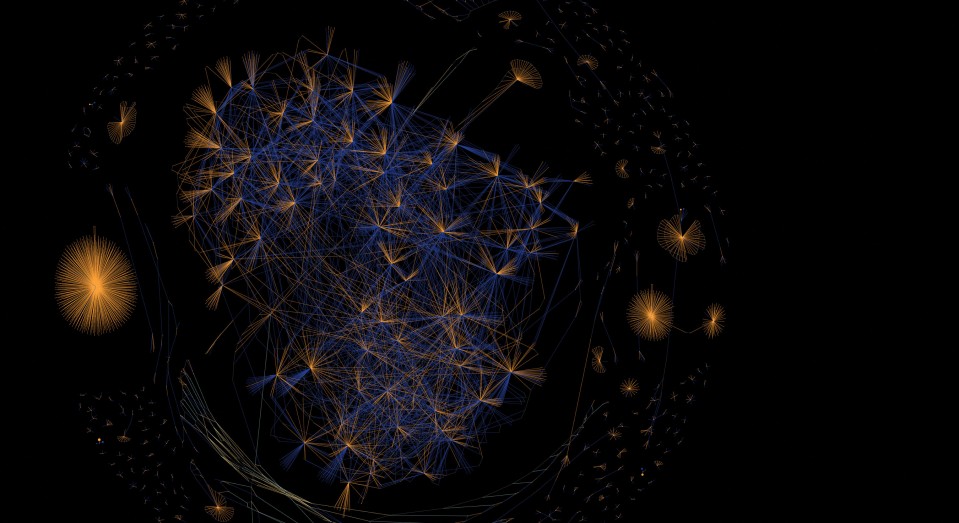

Spiky yellow and blue shapes begin to fill a screen that spans an entire wall in a lab at Imperial College London. The shapes emerge from empty space as the display pulses and dances. The visualization is hypnotic and confounding, but it makes sense once you realize what you’re seeing. I’m watching the Bitcoin blockchain grow in front of me.

A ragged blue circle pops up, and William Knottenbelt, a researcher at the college, provides live commentary. “Here you see somebody taking in Bitcoin and then paying it out to thousands of other people,” he says.

“So this might be a mining pool paying out rewards to the people who have contributed to finding some blocks.” He points to a curious cluster of shapes on the screen.

“Ah, this structure here is interesting,” says Knottenbelt. Several blue circles appear—more payouts to multiple accounts—but they are knitted together by a cross-hatch of yellow lines. It looks as if someone scribbled on the display with a Sharpie.

What Knottenbelt has just noticed could be the first evidence of a sophisticated criminal at work.

An industry has sprung up to help fight back. New forensic tools are allowing authorities to follow the money through cryptocurrency networks that are turning out to be far less private than their founders hoped. Just as closed-circuit cameras turned bank robbers from celebrated criminals into easily caught rubes, researchers hope that their advances can turn anonymous thieves into known prisoners, and make the cryptocurrency world safe for the average customer.

The opportunities in cryptocrime

If you’re up to no good, cryptocurrencies tick a lot of boxes. The only thing tying you to an account in Bitcoin or Ethereum or NEM or a thousand other cryptocurrency systems is an address, typically a random string of letters and numbers. You can have as many addresses as you like, and in principle, there is no obvious way to tie them together or identify their owners. What’s more, money in these accounts can be transferred without intermediaries and across international borders as easily as sending an e-mail.

“Instead of meeting you in a dark car park to hand over a suitcase of money, I can be sitting with a laptop on a balcony in Monaco,” says Jeffrey Robinson, an investigative journalist and author of 30 books on financial crime, including BitCon: The Naked Truth about Bitcoin.

Clever criminals are embracing the new opportunities. A 2018 study by blockchain analysis startup Elliptic and the Center on Sanctions and Illicit Finance, a US think tank, found a fivefold increase in the number of large-scale illegal operations working on the Bitcoin blockchain between 2013 and 2016. By analyzing the history of more than 500,000 bitcoins, they identified 102 criminal entities—including dark-web marketplaces, Ponzi schemes, and ransomware attackers—and showed that many of the coins in their study could be linked back to them.

Ninety-five percent of all laundered coins tracked by the study came from just nine dark-web marketplaces, including Silk Road, Silk Road 2.0, Agora, and AlphaBay. These are notorious online bazaars where a person can buy banned goods like drugs and weapons and pay for services like prostitution or murder-for-hire. “On the dark web you can even buy legal advice,” says Robinson. “There are lawyers down there willing to take Bitcoin to tell you how to avoid getting caught with Bitcoin.”

Other types of organized crime are emerging as well. Hackers have embraced Bitcoin as their payment of choice for ransomware attacks. Such attacks spiked in 2016, with nearly 16 percent of tainted coins linked to outbreaks of malware like Locky. The trend continued in 2017 with WannaCry and NotPetya, which held hostage computer systems in hospitals and businesses across the world. In March of this year, municipal government systems in Atlanta were rendered useless by a ransomware attack whose perpetrators demanded about $51,000 in Bitcoin.

Cryptocrime is even infecting the offline world. The last few months have seen a flurry of real-world hold-ups in which victims were forced to hand over account details at knifepoint. “Suddenly, if you have a lot of crypto you’re in physical danger,” says Imperial College’s Knottenbelt.

And yet, since every Bitcoin transaction is recorded in a distributed public ledger, ill-gotten gains can be tracked. Anyone can download the entire transaction history of Bitcoin—which currently weighs in at around 160 gigabytes—and examine it, or use a website such as Blockchain.info or Block Explorer to check it out in a browser.

Such analysis helped unravel one major heist. In 2014, Mt. Gox, then the largest Bitcoin exchange in the world, was hacked by unknown thieves who stole 850,000 bitcoins, then worth more than $450 million.

As Mt. Gox spiraled into bankruptcy, its trustees enlisted a crack forensics team to help find the missing coins. What they found was a mess. “Mt. Gox didn’t understand how many bitcoins they owed people and how many bitcoins they actually had until they noticed they were gone,” says Jonathan Levin, who led the investigation. Levin and his team eventually tracked the funds to an exchange called BTC-e, where the trail went cold.

Though they couldn’t get most of the missing coins back, “that investigation gave us the idea to develop a tool that other people could use,” Levin says. His company Chainalysis, born of that effort, builds tools for bitcoin businesses wanting to understand their customers better and for law enforcement agencies seeking criminals. Other companies, like Block Seer and Elliptic, offer similar tools and services.

According to Tom Robinson, cofounder and chief data officer of Elliptic, the majority of the world’s Bitcoin exchanges use the company’s software to screen transactions. It checks whether they can be connected to ransomware wallets, dark marketplaces, or theft, for example. Elliptic has helped provide evidence in several criminal cases, including one involving a man who bought parts for AR-15 automatic rifles on the dark web and a handful of drug busts.

Since the company was set up five years ago, Robinson estimates, a trillion dollars’ worth of Bitcoin transactions have been screened using its software—even though there have been only around 300 billion dollars’ worth of Bitcoin transactions ever. That’s because some transactions are screened multiple times; Elliptic recommends that its customers rerun analyses on older transactions because information about dodgy accounts is being updated all the time. “You need to keep checking,” Robinson says.

Robinson won’t name his clients, but a quick search on USAspending.gov reveals that they include the US Drug Enforcement Administration, the Internal Revenue Service, the FBI, and Immigration and Customs. Chainalysis works with those and more, including financial regulators like the SEC. Chainalysis also says that Europol and more than half the police forces in Europe are using its software.

The US Treasury’s interest in the blockchain reflects the fact that crypto-crime isn’t limited to coin heists and black markets. It’s also about fraud and tax evasion. “This is going to be an interesting tax year,” says Jeffrey Robinson. “It’s the first time in the US where they’re cracking down on Bitcoin exchanges for tax purposes.”

How to trace the untraceable

Much of what these companies do builds on techniques introduced by Sarah Meiklejohn, then at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues in 2013. The basic idea is simple. By examining blockchain activity closely, you can spot accounts that appear to belong to the same Bitcoin wallet and are thus controlled by the same entity. The process is known as clustering. Multiple addresses initiating the same transaction might begin to look like one person or organization consolidating smaller funds into one bigger pot, for example. Another telltale sign is when change from a Bitcoin transaction is routed back into an account different from the one where the funds started off. In time, the chaos resolves itself into regular patterns.

Once multiple accounts have been linked to the same owner, you can try to figure out who that owner is. Linking Bitcoin accounts to real-world identities is possible because information tends to leak out. Regulated cryptocurrency exchanges—generally those in the US or Europe—must follow know-your-customer and anti-money-laundering rules, which require people to hand over identification before using their services. Some people are even so careless as to post their supposedly private Bitcoin addresses in online forums. “What people forget is that the blockchain is just one half of the equation,” says Knottenbelt.

Chainalysis and Elliptic now use machine learning to help cluster addresses. Soon it might even be possible for an AI to police blockchains in real time.

The wall-size data visualization at Imperial College is a step toward that. The blue-and-yellow tangle that caught Knottenbelt’s eye was a coin tumbling network, a sequence of transactions deliberately designed to make it harder to track individual coins. It’s like dropping money into a jar, shaking it about, and then taking it out again: the amount doesn’t change, but it’s hard to tell which coin was which. The effect is much the same as if you move money through a bank in a place like the Cayman Islands, where there are strict secrecy laws around banking.

Staying one step ahead

However, tumblers aren’t necessarily a sign of criminal activity. “Some people just do it for privacy reasons,” says Knottenbelt. And in any case, there are better ways for criminals to cover their tracks. As the limits to Bitcoin’s privacy become more apparent, people are moving to new cryptocurrencies, like Zcash and Monero, that reveal almost nothing about the transactions recorded on their blockchains.

Zcash uses a so-called zero--knowledge proof to verify transactions. This is a mathematical way to confirm that a transaction took place without revealing any information about who was involved or how much was transferred. Zcash also lets you hand back coins and have fresh ones mined, the equivalent of trading your marked bills in for clean ones at the bank.

Monero, meanwhile, is effectively a big tumbling network. When you want to transfer coins, your address is mixed in with a bunch of others so that no one can tell which one was spending the money.

Zcash and Monero certainly take privacy to the next level. But that doesn’t mean they’ll never give up their secrets. Meiklejohn points out that sloppy user behavior, such as posting your private address in forums, will again leave behind clear trails, just as with Bitcoin.

What’s more, Monero gives users the option to carry out transactions with no obfuscating coins mixed in. This removes the privacy for that particular transaction and adds a way for researchers to disentangle, through a process of elimination, any mixers that subsequently include those coins. Malte Möser at Princeton University and colleagues estimate that 62 percent of inputs to Monero transactions are vulnerable to this analysis. When users of Zcash and Monero start to hemorrhage clues, the likes of Meiklejohn and Möser will be ready.

Perhaps the biggest problem for law enforcement, though, is the large number of unregulated exchanges, where criminals can wipe away the traces of their theft by laundering the stolen cryptocurrency into other forms of wealth. Many exchanges defy regulation out of principle: the likes of BTC-e and the conversion service Shapeshift, for instance, sell themselves on the promise of asking for no identification from their users. Shapeshift founder Erik Voorhees is especially outspoken about the political implications of regulation.

Security and cryptocurrency researcher Ross Anderson at the University of Cambridge, UK, argues that these exchanges thrive in part because laws are ineffective. “The problem with anti-money-laundering generally is that nobody wants it done right,” he says. “If you’re a city bank, you don’t want to know that John Gotti is a customer, and so banks would never tolerate a law that said whoever banks the mafia will go to jail.” If that’s how the world works, why should crypto exchanges be different?

Banks and financial companies are experimenting with using cryptocurrency to create smoother payment systems. But the technology is also supporting a new generation of illicit activity, providing new ways to steal, blackmail, commit fraud, and break international sanctions.

Anderson’s cynicism about the authorities’ willingness to act has led him to formulate a plan to take down the cryptocrime system himself. He is creating what he calls a taintchain—a public list of bitcoins with clear links to criminal activity. “What I’m going to do is publish a list of all the stolen Bitcoin and the software you need to generate it so that everybody can check it for themselves,” he says. Exchanges would then think twice about handling stolen coins.

Even if regulation were stricter, however, it’s not clear that it would make a difference. “I don’t think outlawing anything is going to help anyone,” says Knottenbelt. Driving the tech underground, he argues, will simply mean that transactions will be hidden rather than broadcast openly on the internet, making it even harder for researchers like Meiklejohn to analyze the money flows and find the thieves.

Surprisingly, Meiklejohn herself turns out not to worry too much about regulation—or lack of it. “Once you’ve isolated the problem to bad exchanges operating outside of typical jurisdictions, then you’ve kind of won,” she says. Take BTC-e, an exchange based in Russia that was known to have taken a lot of criminal money. A lot of ransomware operators appeared to be using BTC-e almost exclusively. It was also where the missing Mt. Gox funds were last seen before the trail vanished.

But in July 2017 it was closed down. US authorities arrested staff and seized computers at one of the exchange’s data centers, and Alexander Vinnik, its suspected operator, was arrested. “They clearly were not going to respond to subpoenas,” says Meiklejohn. “On the other hand, this is something law enforcement is well aware how to deal with.”

Meiklejohn sees her work as distilling cryptocrimes to the type of crime familiar to law enforcement. Armed with leads from Elliptic and others, good old-fashioned policing will then do what it does best.

The biggest cyber-heist in history

For the time being, however, the cybercriminals are still a step ahead. Although researchers can now watch thefts of cryptocurrency on blockchain networks happen in close to real time, they can’t connect them to the real world fast enough to stop even monumental capers.

The biggest cyber-heist in history happened at 3 a.m. Japan time on a January morning this year. Someone, or more likely someones, made off with more than half a billion dollars’ worth of a digital currency called NEM from the Tokyo-based cryptocurrency exchange Coincheck. No one at the exchange raised alarms until lunchtime, and the culprits got an eight-hour head start.

When news finally reached NEM Foundation vice president Jeff McDonald in Tulsa, Oklahoma, he went right to the chain. The funds had been taken from a software wallet connected to the internet—an insecure storage locker that Coincheck says it was only using because of a fault elsewhere in its system. “It’s basically like leaving your ATM card out with the PIN number written on it,” says Alexandra Tinsman, the NEM Foundation’s communications director. All of the 523 million stolen coins were funneled first through a single account before being split among several others.

To stop the thieves from cashing out their loot into a fiat currency, the NEM team rushed to flag the stolen coins and put exchanges on alert. The day after the hack, the NEM team had identified and published the addresses of 11 accounts where funds had ended up. Each was labeled with a tag that read “coincheck_stolen_funds_do_not_accept_trades : owner_of_this_account_is_hacker.” But because they didn’t know who owned the accounts, the NEM team was unable to do much more than attempt to block the exits.

A waiting game ensued. Unable at first to cash the stolen coins out of the NEM network, the thieves moved them around it. These movements were all visible on the public blockchain. The NEM team tracked the coins to Canada and then watched as some of them returned to Japan. But even though NEM never took its eyes off the marked notes, the thieves still got away. In the end they were able to make it to an unregulated exchange and cash out at least half the stolen coins. In March, the NEM team announced it was giving up the chase.

Stung by the massive theft, Coincheck announced that it would no longer deal in Zcash, Monero, or Dash, another anonymous currency. It’s among the first exchanges to cut off those coins.

Coincheck’s move is part of a larger effort to bring law and order to this new frontier of money. The US government is toying with the idea of creating a blacklist of cryptocurrency addresses that are associated with criminal groups, such as terrorists, drug traffickers, and sanction-busters. One possibility is that it would become illegal to deal with blacklisted addresses.

The NEM thieves have escaped, for now. But future technology could snare them yet. As the forensic techniques and tools get better, previously overlooked evidence will come to light like DNA traces at a years-old crime scene. Every time the authorities shut down a Silk Road or BTC-e, that sends a signal, says Jeffrey Robinson: “They’ll get the rest of them, one by one.”

Douglas Heaven is a freelance writer based in London.