Humans and Technology / VR

Even if Magic Leap’s goggles suck, it can probably still make money off them

Those who’ve tried Magic Leap One say it’s functional, but the company’s got a boatload of patents it could license to satisfy investors regardless.

It makes a lot of sense to be skeptical of Magic Leap, the mysterious augmented-reality company that has raised well over $2 billion since 2011 but has yet to release a product.

The Florida-based company said its headset, a pair of black, bug-eyed goggles called Magic Leap One, will be available for developers this year, and a company spokesman confirmed that Magic Leap shipped some headsets out in recent weeks to select developers in an early access program. But we still don’t know exactly when it will be shipping en masse to any interested developer, how much it will cost, or how well it will work.

Few people outside the company have seen the device, let alone tried it. In March, Magic Leap released software tools that developers could use to start making apps for the device; those without access to the device have to use a software-based simulator to get a sense for what their creations will actually look like through the lenses of the headset.

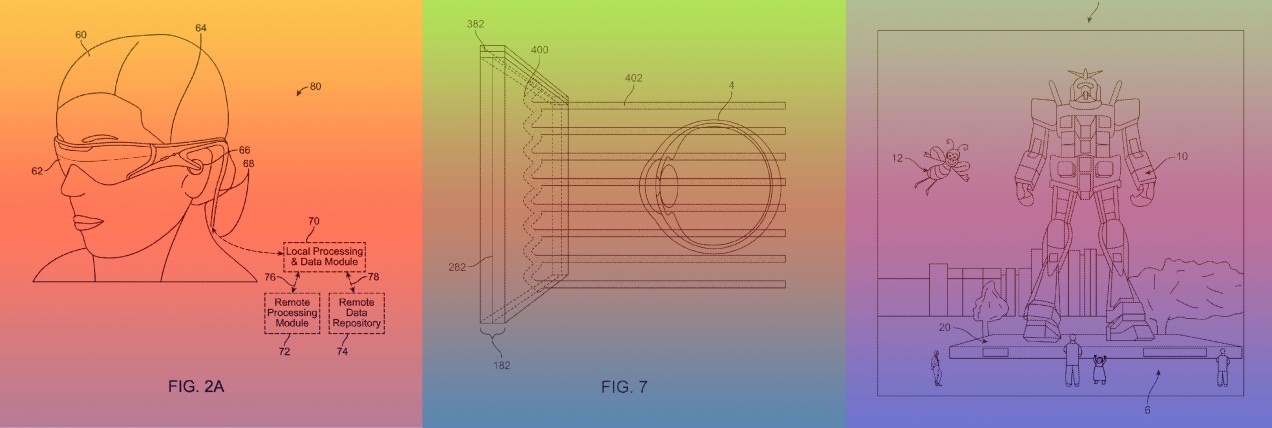

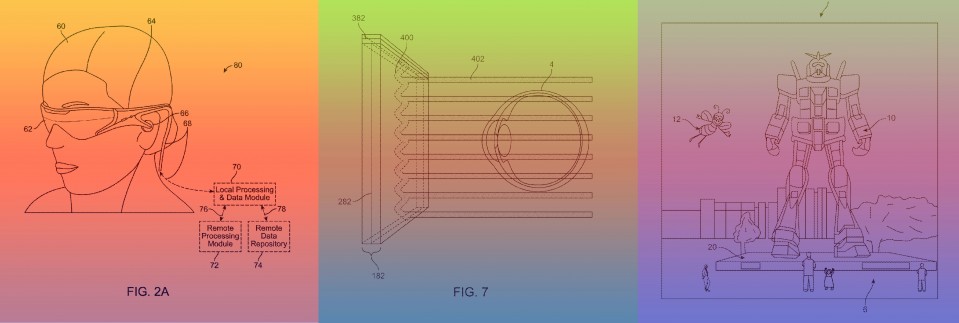

The company has built up a trove of dozens of patents over the past several years that could be licensed to other companies as a sort of fallback plan if the headset fails. And yet, interviews with investors and current and former employees—along with some test footage shown off at the Game Developer Conference in San Francisco last month—indicate it may actually be releasing a product in the near future that has some promising capabilities. If that’s the case, Magic Leap could deliver virtual whales, robots, and other objects to your living room that look realistic and are fun (and perhaps helpful) to interact with—eventually.

“It looks ready to me,” said Bing Gordon, a partner at Magic Leap investor Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, who last tried out the headset at GDC. Gordon wouldn’t say much about what he saw through its lenses, but he did note that the visuals looked better than what he’s seen with other AR headsets he’s tried, including rival Microsoft’s HoloLens (that $3,000 to $5,000 headset came out in 2016 and is still limited to developers).

Gordon’s experience was echoed by a former Magic Leap project manager who said that when he tried on the headset in the late summer or early fall, it had the same look as the Magic Leap One and was “all functional.”

The former employee, who worked on the company’s developer resources and software tools until he left late last year, said that when he last saw it, the headset’s capabilities were limited. Still, he has tried demos including a Star Wars experience that re-created the snowy Battle for Hoth from The Empire Strikes Back, complete with a rebel base, AT-AT Walkers, and spaceships flying by trying to blast him; blowing fans placed in the demonstration room were used to add wind effects. (Lucasfilm, which runs the Star Wars franchise, is a Magic Leap content partner.)

Though he noticed some issues like jittering visuals when trying it, “images were very crisp,” he said.

“It’s not vaporware. It’s real,” he said. “But it’s still obviously a work in progress.”

Secretly showing off

Magic Leap, too, wants to give the impression that a product is coming along, though it won’t get too specific. Speaking at the sidelines of GDC after participating in a panel discussion for Magic Leap developers, Rio Caraeff, Magic Leap’s chief content officer, said over 150 developers are currently working with the hardware. Magic Leap also gave demos to “hundreds” of developers during the conference, he said.

“I can assure them, it’s very real,” Caraeff said.

A few short videos the company played at the talk on building applications for what it dubs “spatial computing” intended to drive this home with developers, though most of them probably hadn’t tried it yet.

In one of the clips, colorful digital sparks shot out of the sides of actual lamps. Magic Leap interaction director Aleissia Laidacker, who spoke on the panel, said the experimental imagery made her excited about the idea of incorporating internet-connected gadgets like smart lights into developers’ augmented-reality creations.

In another clip, a virtual robotic man stood in front of a real couch, sat down convincingly on it, and walked behind it so his lower half was properly hidden—examples of several things that are tricky to do convincingly with augmented-reality technology that, presumably, are possible to build and show with Magic Leap One.

And yet questions remain about how well Magic Leap’s headset will work in everyday environments like your house, your office, and so on. Magic Leap has publicly released only a few images and videos shot with its technology, and many of them, including the ones shown at GDC, were recorded in dimly lit rooms—the kind of thing that could indicate it can’t project virtual images well in bright environments.

Asked about this, Caraeff said he didn’t know and couldn’t comment on it. He then added that the headset “works in any room, and in a variety of lighting conditions.”

Caraeff also pointed out that the product is still in development, so videos like ones showed off at GDC were simply meant as a sneak peek.

“This is raw, this is what we’re doing, this is what we’re working on,” he said. “It’s not about anything but that.”

The former Magic Leap project manager said the demos he saw were usually presented in a prepared demo room, but one that was well lit, and he tried the technology out in a regular office environment, too.

The price of the headset—both the one that will be sold to developers and, presumably, eventually to consumers—is also unclear. In an interview in February with Recode, Magic Leap founder and CEO Rony Abovitz said that initially the headset will be priced in the same range as a “premium computer,” which could be anywhere from around $1,000 to several thousand dollars. (In that same interview, he also indicated that a future, more consumer-geared headset would be around $1,000.)

IP options

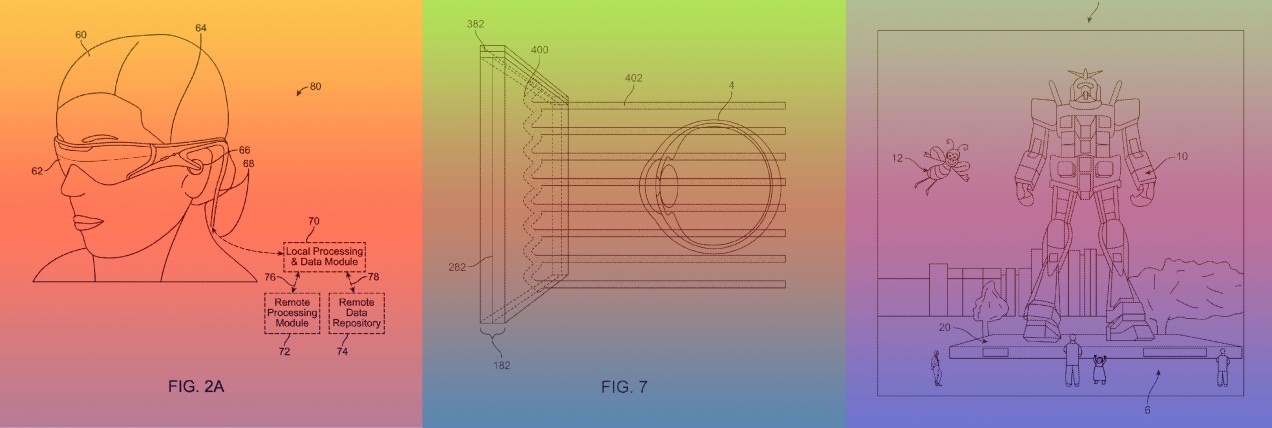

Developers may be willing to pony up for a fancy headset, but consumers are likely to balk at that kind of pricing, even if it works well. Fortunately, hardware isn’t Magic Leap’s only bet. For years it has funneled some of its funding dollars into filing for a slew of patents related to things such as its imaging technology and headset; it had filed over 230 patent applications as of early April, and been granted nearly 50. The ones it received patents for relate largely to technology for projecting and displaying virtual images in real-world environments.

Ostensibly, the patents are meant to protect Magic Leap’s intellectual property and prevent others from copying its technology, and a handful of them are simply patents on the design or design elements of devices like a headset and controller. But the company could also license the intellectual property to help satisfy investors if the headset isn’t a hit (and, one would think, even if it is).

“This kind of stuff is potentially very valuable,” said Peter Menell, director of UC Berkeley’s Berkeley Center for Law & Technology. And besides, he added, the costs of filing for patents are not that high considering how much money the company has raised.

Pierre-Alexandre Blanche, a research professor at the University of Arizona who specializes in holography and diffractive optics, knows some of the people who are working on these patents—such as his colleague Hong Hua, an optical sciences professor who is also a contractor for Magic Leap. Considering these folks’ backgrounds in holography, diffraction, and 3-D technology, he thinks the patents, at least, must be valid.

“It’s not just fluff,” he said.

Ozi Amanat, founder of VC firm K2 Global, which invested in Magic Leap’s $542 million series B funding round in 2014 along with Kleiner Perkins, Google, and others, said he saw the intellectual property as a buffer to his investment.

“It definitely gave me a lot of comfort looking at the company,” said Amanat, who is based in Singapore.

That said, Magic Leap is still somewhat of a mystery to him, too; he hasn’t yet seen a demo of its technology (he relied on other investors’ positive views, he said).

Still, he said, “I think something good is coming.”