Artificial Intelligence / Machine Learning

Progress in AI isn’t as Impressive as You Might Think

A new report gauges how far we’ve come, dampening ideas that machines are approaching human-type intelligence.

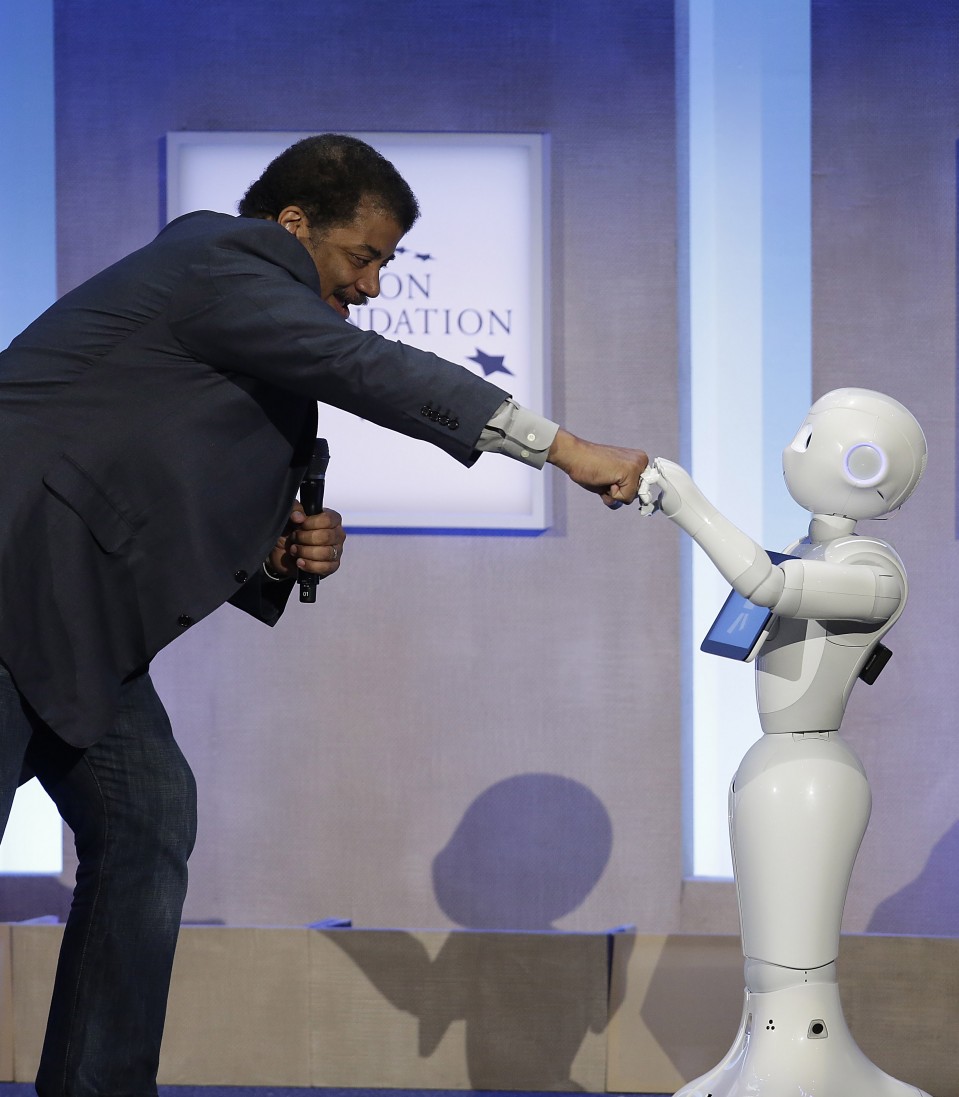

With so much excitement about progress in artificial intelligence, you may wonder why intelligent machines aren’t already running our lives.

Key advances have the capacity to dazzle the public, policymakers, and investors into believing that human-level machine intelligence may be just around the corner. But a new report (PDF), which tries to gauge actual progress being made, attests that this is far from true. The findings may help inform the discussion over how AI will affect the economy and jobs in the coming years.

“There’s no question there have been a number of breakthroughs in recent years,” says Erik Brynjolfsson, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and one of the authors of the report. “But it’s also clear we are a long way from artificial general intelligence.”

Brynjolfsson points to remarkable advances in image classification and voice recognition. But computers trained to perform these tasks cannot do much else, and they cannot adapt if the nature of the task changes slightly or if they see something completely unfamiliar.

The report is part of an ongoing effort, called the AI Index, to quantify progress in artificial intelligence and identify areas where more is still needed. The other authors are Yoav Shoham, a professor at Stanford; Raymond Perrault, a researcher at SRI; Jack Clark, director of policy at OpenAI; and Calvin LeGassick, project manager for the AI Index.

Brynjolfsson is also the director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, an effort to understand the economic and social implications of AI and robotics.

Brynjolfsson says the new report should help with these sorts of economic investigations. “The next thing to ask is how this [progress] will affect the economy and jobs,” he says.

The report uses several metrics to measure the current AI boom, including growth in job postings related to AI, the rise of AI-focused startups, and the number of contributors to major open-source AI projects. It also points to existing benchmarks in specific areas such as image processing, natural-language understanding, and computerized play of chess, Go, Atari games, and more.

Through interviews with leading AI experts, the report also tries to identify key areas where progress is still needed. Several point to the need for huge amounts of data to train current AI systems, and to their inability to generalize about solving a variety of problems.

If machines aren’t nearly as intelligent as we’d often like to believe, it’s natural to wonder what that might mean for the tech industry that’s betting so heavily on AI today.

“There is, clearly, an AI bubble at present,” writes Michael Wooldridge, an AI researcher who leads the computer science department at the University of Oxford. “The question that this report raises for me is whether this bubble will burst, [like] the dot-com boom of 1996-2001, or gently deflate, and when this happens, what will be left behind?”

Regardless of when artificial general intelligence might or might not arrive, that seems like a good question to ask.