Biotechnology / Genetic Engineering

Tracking the Cost of Gene Therapy

Though expensive now, prices could get cheaper for more common diseases.

Gene therapy, which introduces new genetic material into a person’s DNA, was developed as a revolutionary way to treat some of the rarest syndromes on earth.

Drug companies have attached astronomical prices to these narrowly targeted treatments. In fact, the prices are so high that one has already been pulled from the market in Europe, and the other has struggled to attract patients.

A treatment approved last week could change the equation. Yescarta is the second example of a gene therapy that modifies the DNA in a person’s immune cells to go after cancer. What’s different about Yescarta is that it could treat far more patients than the other gene therapies approved so far.

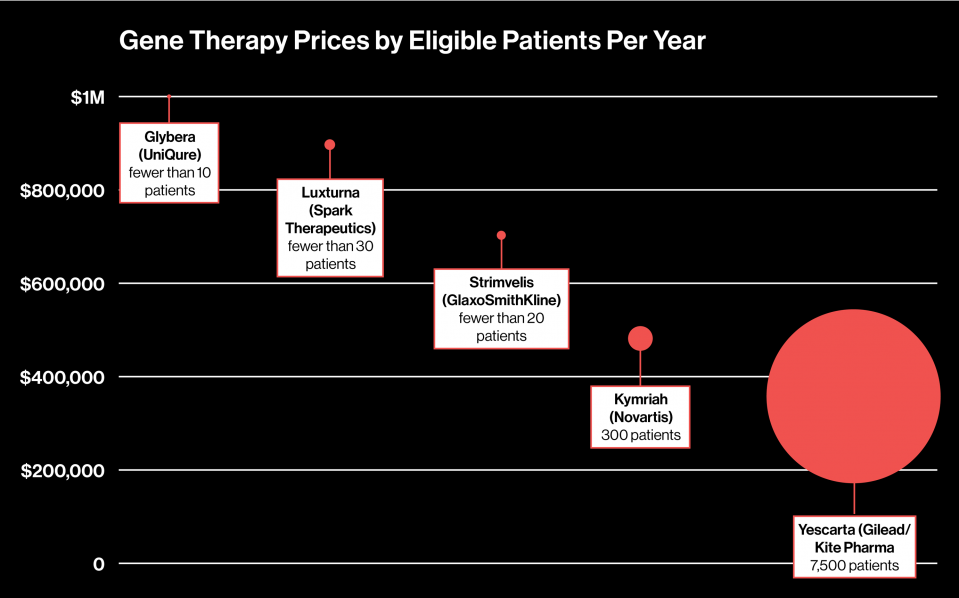

To see if there’s a connection between the price of a gene therapy and the estimated number of patients it will treat per year, we decided to plot those figures for the approved gene therapies in the U.S. and Europe and one that’s pending approval in the U.S.

Herman Sanchez, managing partner at life science consulting firm Trinity Partners, says there is a correlation between the patient population and price of the therapy: the fewer eligible patients, the more expensive it is. As you can see, prices range from $373,000 to $1 million, while the number of patients per year is as low as just a few to 7,500.

“The smallest diseases have more pricing power in the marketplace,” he says. “That’s usually due to the fact that payers don’t have to deal with a lot of patients.”

So far, Yescarta is the outlier. It could help as many as 7,500 people, according to Gilead, the biotech giant that acquired the drug’s maker, Kite Pharma in August. Compare that with the tiny eligible populations for the two gene therapies approved in Europe, Glybera and Strimvelis. Meanwhile, in the U.S., Novartis says about 300 patients a year will be eligible for its gene therapy Kymriah, which treats a type of childhood leukemia. With more patients, Gilead was able to set a lower price but might see higher overall revenues in the end.

Though Yescarta’s price still prompted outcries from patient advocates, it bodes well for gene therapies in the pipeline for diseases with more patients, like hemophilia and sickle-cell, which affect about 20,000 people and 100,000 in the U.S., respectively.

If the targeted disease is more common, “there will be more pricing pressure,” Sanchez says.

Next up for approval is a gene therapy called Luxturna that restores some vision in patients with an inherited type of blindness. Earlier this month, a panel of outside experts unanimously recommended that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approve Luxturna, which is made by Spark Therapeutics. The agency will make its decision by January 12.

Spark says about 1,000 to 2,000 total people in the U.S. could be eligible for its therapy, which improves sight by replacing a mutated gene in the retinal cells. The company declined to give projections on how many patients it might treat per year, so we based our figures on the estimated incidence of the form of blindness Luxturna treats. Analysts have estimated the therapy could cost $800,000 to $1 million to treat both eyes.

What all this means for companies, insurers, and patients is up in the air. Companies like Spark will face a pricing dilemma when their therapies win regulatory approval. Insurers in the U.S. have so far stayed mum on whether they will cover them. Meanwhile, patients with serious medical conditions are hoping they won’t be priced out of a cure.