Intelligent Machines

Security Robots Get a Designer Makeover

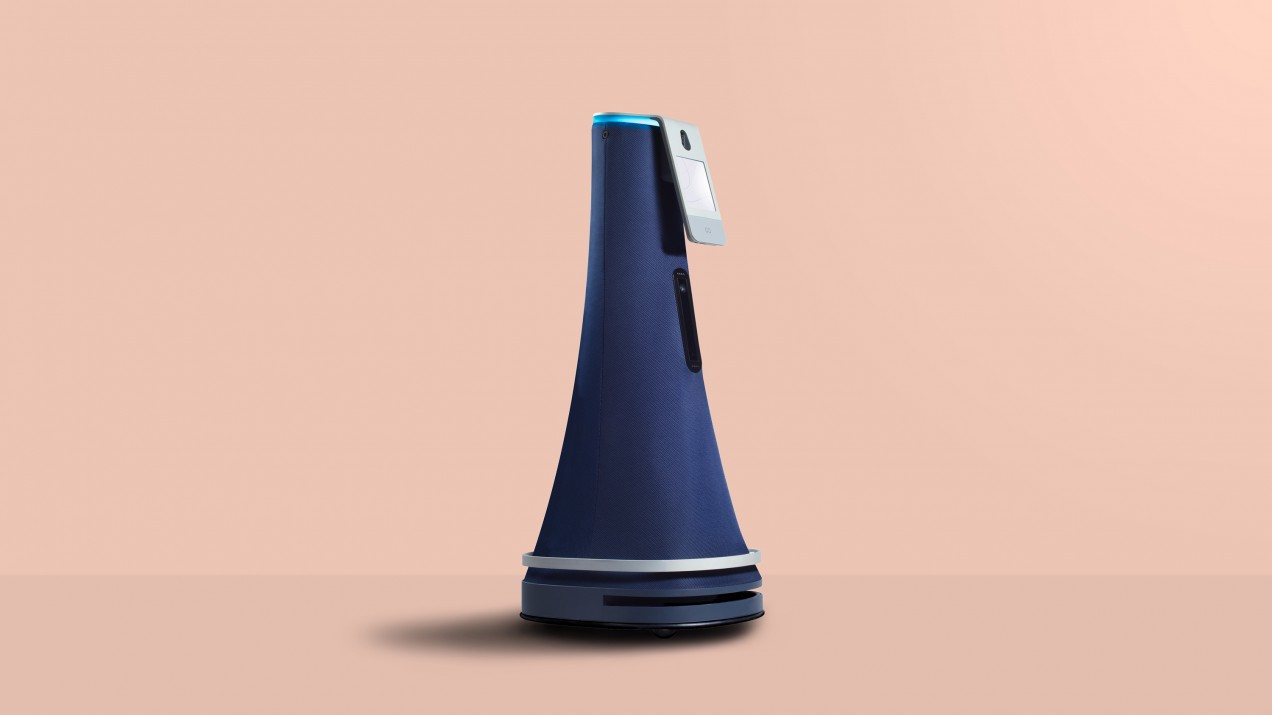

Startup Cobalt gives bots a warm and fuzzy look to help humans feel more comfortable around them.

Would you feel more comfortable interacting with a robot security guard if it looked more like a fancy, fabric-covered sculpture than a sterile droid?

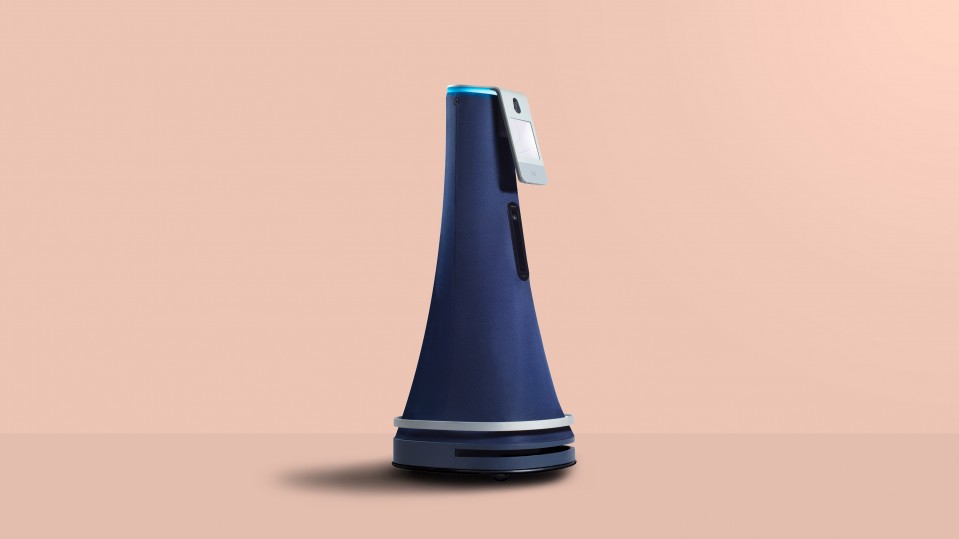

That’s the thinking behind a startup called Cobalt, whose new robot security guards were designed by well-known industrial designer Yves Behar and his company, Fuseproject. Meant for patrolling inside high-end offices and interacting with people, Cobalt’s bots are like sleek, human-size board-game pieces with fabric stretched over swooping metal ribs. A touch screen on one side lets office workers communicate with a remote operator when needed.

“For the most part, it’s providing peace of mind to employees. In the same way that a security guard is there all the time—you recognize them, you can go talk to them if you have questions—we provide that same level of interaction,” says Travis Deyle, Cobalt’s cofounder and a member of MIT Technology Review’s 2015 TR35 list of young innovators.

Deyle and his cofounder, Erik Schluntz, who both have backgrounds in robotics and worked together on smart contact lenses at the Google X research lab, started Cobalt in Palo Alto last March but kept quiet about it. Two prototypes later, they are now beginning to manufacture its first version of their bot and talk about what it is they’re doing.

The first of the startup’s robots will be deployed later this month to some paying customers, Deyle says, including a couple of large finance companies and some publicly traded technology companies. He won’t name any of them, however, and the company also declined to say how much a robot costs. Schluntz says it’s “cheaper than a guard.”

As they get out in the world, the bots will join a growing horde of robots meant to interact with people, ranging from existing security robots to ones roaming around hotels and down city streets.

Initially, at least, Cobalt’s robots will be spending much of their time alone. They’ll patrol buildings primarily on nights and weekends, Deyle says, and if they detect an intruder or anything else anomalous—a window or door that shouldn’t be open, for instance—they will rope in a human operator.

Each robot is equipped with a slew of cameras, microphones, lights, and sensors, including lidar and depth cameras for building a map of its environment (which the company augments with data about the location of doors and windows) and a ring of LEDs at its top that can signal things like where the robot is turning. Its battery is meant to last for a full night, though it will return to a charger each hour to top off. It also has a touch screen on the front so people can video-chat with a remote operator, and a badge reader so that employees can identify themselves to the robot. It can sense things like glass breaking and people calling out to it.

Eventually, Deyle expects the robot to get to a point where it can act almost as a concierge during the daytime—helping escort guests to the right conference room with a map on its display, or letting employees notify it of any problems they spot in the building, like a leak in a bathroom.

With increasing fears that automation will cut into the jobs typically held by humans, Cobalt and peers like Knightscope could be seen as competition for existing security guards.

But Deyle says the robots are meant more as helpers, not replacements, because they let one person be, effectively, in many parts of a building at once—something that may make it more affordable for companies to keep an eye out at smaller satellite offices, or in spread-out campuses, where they otherwise might not have a human guard.

Advertisement