Reinforcement Learning: 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2017

By experimenting, computers are figuring out how to do things that no programmer could teach them.

Inside a simple computer simulation, a group of self-driving cars are performing a crazy-looking maneuver on a four-lane virtual highway. Half are trying to move from the right-hand lanes just as the other half try to merge from the left. It seems like just the sort of tricky thing that might flummox a robot vehicle, but they manage it with precision.

I’m watching the driving simulation at the biggest artificial-intelligence conference of the year, held in Barcelona this past December. What’s most amazing is that the software governing the cars’ behavior wasn’t programmed in the conventional sense at all. It learned how to merge, slickly and safely, simply by practicing. During training, the control software performed the maneuver over and over, altering its instructions a little with each attempt. Most of the time the merging happened way too slowly and cars interfered with each other. But whenever the merge went smoothly, the system would learn to favor the behavior that led up to it.

This approach, known as reinforcement learning, is largely how AlphaGo, a computer developed by a subsidiary of Alphabet called DeepMind, mastered the impossibly complex board game Go and beat one of the best human players in the world in a high-profile match last year. Now reinforcement learning may soon inject greater intelligence into much more than games. In addition to improving self-driving cars, the technology can get a robot to grasp objects it has never seen before, and it can figure out the optimal configuration for the equipment in a data center.

Reinforcement learning copies a very simple principle from nature. The psychologist Edward Thorndike documented it more than 100 years ago. Thorndike placed cats inside boxes from which they could escape only by pressing a lever. After a considerable amount of pacing around and meowing, the animals would eventually step on the lever by chance. After they learned to associate this behavior with the desired outcome, they eventually escaped with increasing speed.

Some of the very earliest artificial-intelligence researchers believed that this process might be usefully reproduced in machines. In 1951, Marvin Minsky, a student at Harvard who would become one of the founding fathers of AI as a professor at MIT, built a machine that used a simple form of reinforcement learning to mimic a rat learning to navigate a maze. Minsky’s Stochastic Neural Analogy Reinforcement Computer, or SNARC, consisted of dozens of tubes, motors, and clutches that simulated the behavior of 40 neurons and synapses. As a simulated rat made its way out of a virtual maze, the strength of some synaptic connections would increase, thereby reinforcing the underlying behavior.

There were few successes over the next few decades. In 1992, Gerald Tesauro, a researcher at IBM, demonstrated a program that used the technique to play backgammon. It became skilled enough to rival the best human players, a landmark achievement in AI. But reinforcement learning proved difficult to scale to more complex problems. “People thought it was a cool idea that didn’t really work,” says David Silver, a researcher at DeepMind in the U.K. and a leading proponent of reinforcement learning today.

That view changed dramatically in March 2016, however. That’s when AlphaGo, a program trained using reinforcement learning, destroyed one of the best Go players of all time, South Korea’s Lee Sedol. The feat was astonishing, because it is virtually impossible to build a good Go-playing program with conventional programming. Not only is the game extremely complex, but even accomplished Go players may struggle to say why certain moves are good or bad, so the principles of the game are difficult to write into code. Most AI researchers had expected that it would take a decade for a computer to play the game as well as an expert human.

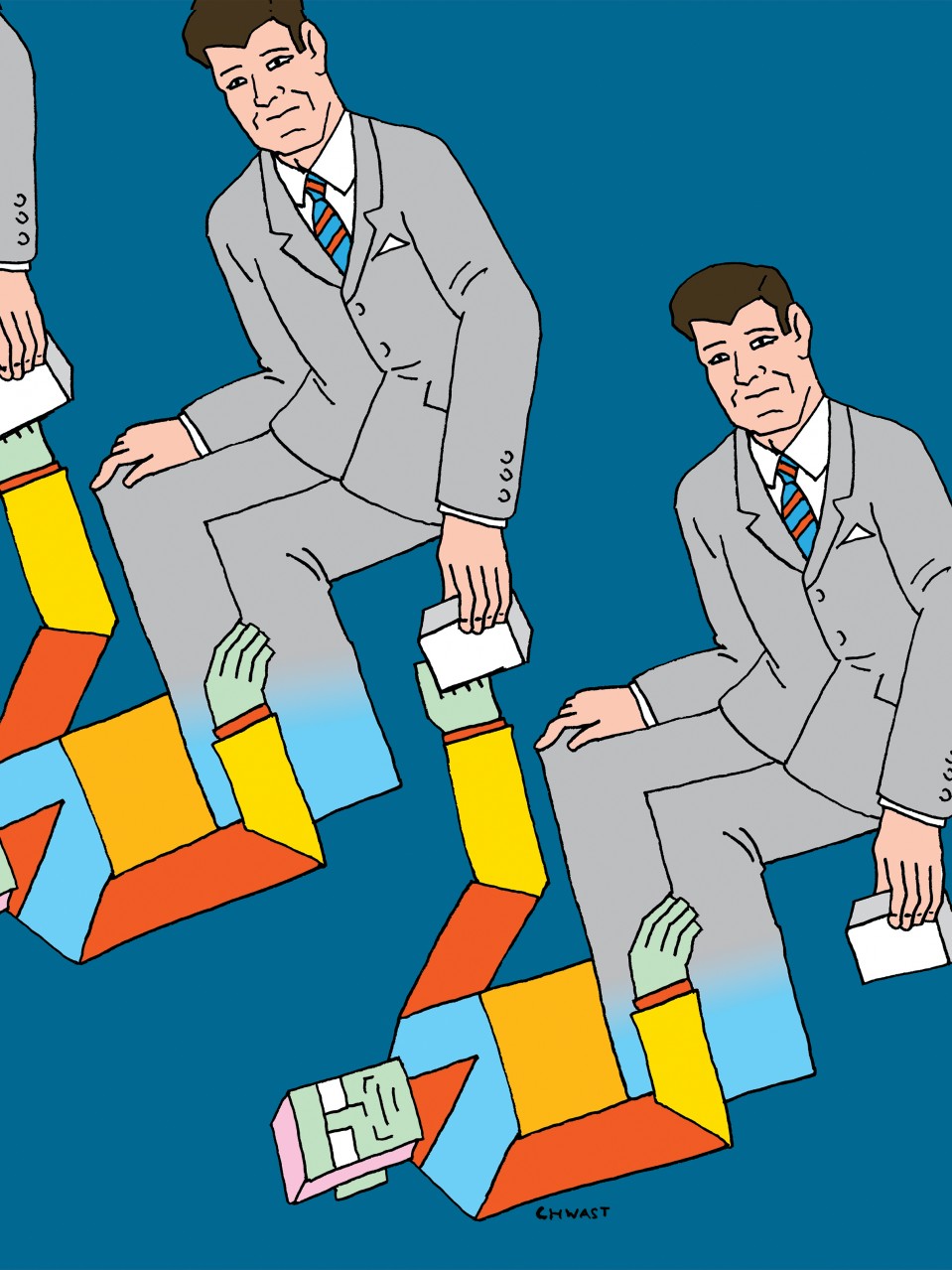

Jostling for position

Silver, a mild-mannered Brit who became fascinated with artificial intelligence as an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, explains why reinforcement learning has recently become so formidable. He says that the key is combining it with deep learning, a technique that involves using a very large simulated neural network to recognize patterns in data (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2013: Deep Learning”).

Reinforcement learning works because researchers figured out how to get a computer to calculate the value that should be assigned to, say, each right or wrong turn that a rat might make on its way out of its maze. Each value is stored in a large table, and the computer updates all these values as it learns. For large and complicated tasks, this becomes computationally impractical. In recent years, however, deep learning has proved an extremely efficient way to recognize patterns in data, whether the data refers to the turns in a maze, the positions on a Go board, or the pixels shown on screen during a computer game.

In fact, it was in games that DeepMind made its name. In 2013 it published details of a program capable of learning to play various Atari video games at a superhuman level, leading Google to acquire the company for more than $500 million in 2014. These and other feats have in turn inspired other researchers and companies to turn to reinforcement learning. A number of industrial-robot makers are testing the approach as a way to train their machines to perform new tasks without manual programming. And researchers at Google, also an Alphabet subsidiary, worked with DeepMind to use deep reinforcement learning to make its data centers more energy efficient. It is difficult to figure out how all the elements in a data center will affect energy usage, but a reinforcement-learning algorithm can learn from collated data and experiment in simulation to suggest, say, how and when to operate the cooling systems.

But the setting where you will probably most notice this software’s remarkably humanlike behavior is in self-driving cars. Today’s driverless vehicles often falter in complex situations that involve interacting with human drivers, such as traffic circles or four-way stops. If we don’t want them to take unnecessary risks, or to clog the roads by being overly hesitant, they will need to acquire more nuanced driving skills, like jostling for position in a crowd of other cars.

The highway merging software was demoed in Barcelona by Mobileye, an Israeli automotive company that makes vehicle safety systems used by dozens of carmakers, including Tesla Motors (see “50 Smartest Companies 2016”). After screening the merging clip, Shai Shalev-Shwartz, Mobileye’s vice president for technology, shows some of the challenges self-driving cars will face: a bustling roundabout in Jerusalem; a frenetic intersection in Paris; and a hellishly chaotic scene from a road in India. “If a self-driving car follows the law precisely, then during rush hour I might wait in a merge situation for an hour,” Shalev-Shwartz says.

Mobileye plans to test the software on a fleet of vehicles in collaboration with BMW and Intel later this year. Both Google and Uber say they are also testing reinforcement learning for their self-driving vehicles.

Reinforcement learning is being applied in a growing number of areas, says Emma Brunskill, an assistant professor at Stanford University who specializes in the approach. But she says it is well suited to automated driving because it enables “good sequences of decisions.” Progress would proceed much more slowly if programmers had to encode all such decisions into cars in advance.

But there are challenges to overcome, too. Andrew Ng, chief scientist at the Chinese company Baidu, warns that the approach requires a huge amount of data, and that many of its successes have come when a computer could practice relentlessly in simulations. Indeed, researchers are still figuring out just how to make reinforcement learning work in complex situations in which there is more than one objective. Mobileye has had to tweak its protocols so a self-driving car that is adept at avoiding accidents won’t be more likely to cause one for someone else.

When you watch the outlandish merging demo, it looks as though the company has succeeded, at least so far. But later this year, perhaps on a highway near you, reinforcement learning will get its most dramatic and important tests to date.