Business Impact

Before PCs Vanish, Microsoft Fights for Relevance in the Cloud

Under Satya Nadella, the software giant hopes to survive by overturning the way it has always done business.

The way to make money in technology,” a young Bill Gates told me in the summer of 1990, “is by setting de facto standards.” It worked, too. For years, Microsoft enjoyed more than 90 percent of the market for several categories of PC software.

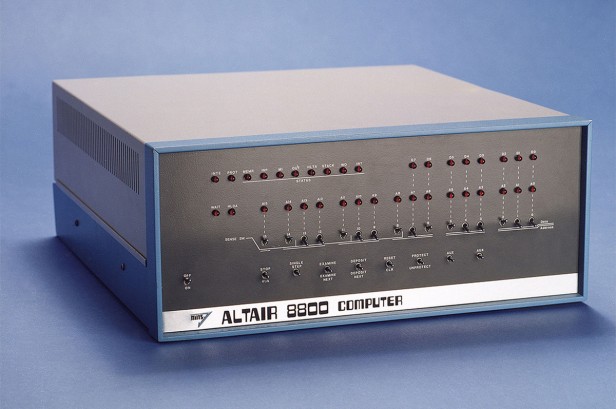

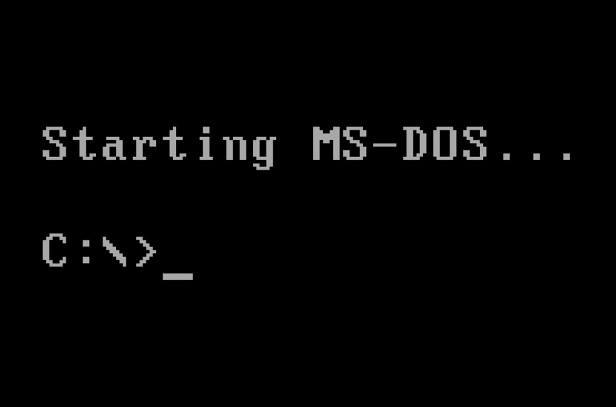

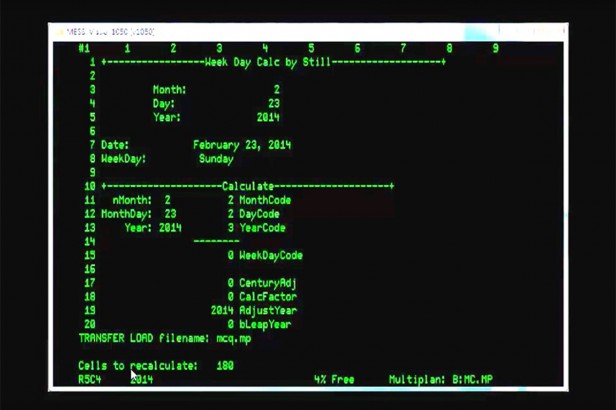

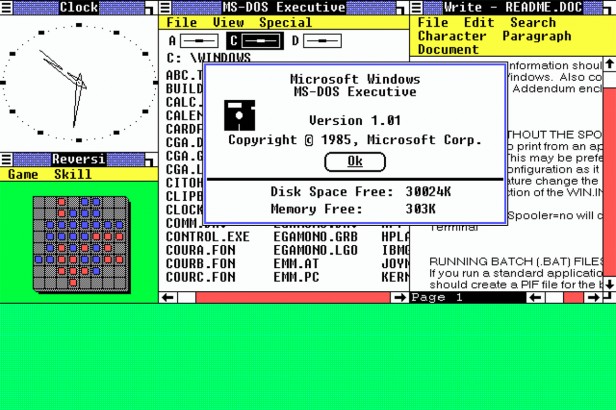

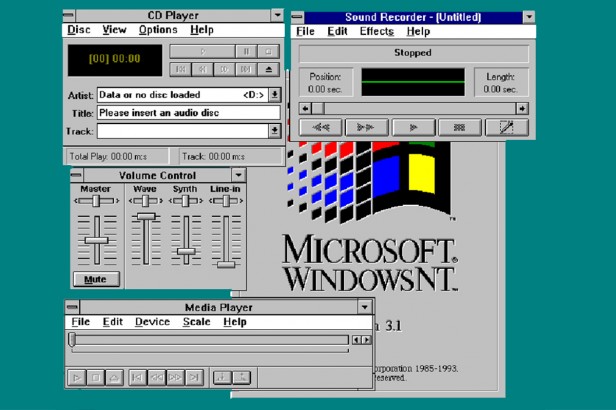

The IBM PC may have defined a hardware standard, but IBM contracted the work of supplying an operating system to Microsoft and, in haste or a corporate fit of unconsciousness, permitted Microsoft to sell its software to other hardware manufacturers. The first microcomputers could do nothing without Microsoft’s version of the BASIC programming language. The company had the operating systems (first MS-DOS, then Windows) that made PCs possible. It sold the word processors and spreadsheets people needed to work on PCs, and it bundled those productivity applications into a single product, Office, that destroyed other PC software companies. Anytime potential competitors arose, Microsoft copied the features of their products and pushed them into its operating systems or Office. Even when the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission thought Microsoft competed unfairly, the company would negotiate with the government, and compete some more. By setting standards that were good enough and cheap enough, Microsoft got close to its stated goal of putting a “computer on every desk and in every home” and for a time was the most valuable company on Earth.

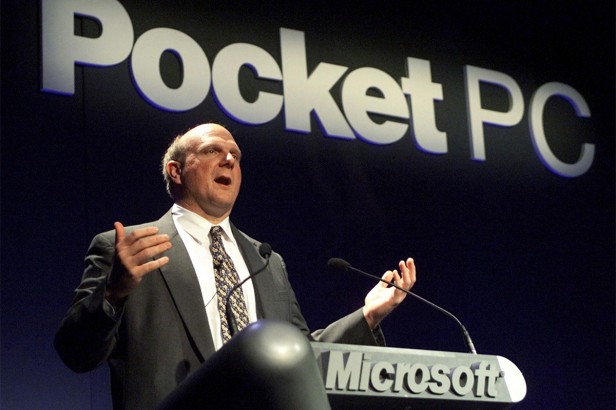

It is still the third or fourth most valuable company. But Gates is long gone from the everyday at Microsoft, and his successor, Steve Ballmer, is gone, too. Their playbook was the same, but the playing field changed, as sales of personal computers declined with the rise of smartphones and tablets. Microsoft Windows still runs 90 percent of personal computers, but in 10 years we won’t need Windows, because we’ll use mobile devices that run much of their software and store most of their data in the cloud. This year the public cloud is a $200 billion business, growing in some sectors at more than 50 percent per year. How do you slap a Windows sticker on that?

It was with this looming crisis in mind, then, that Microsoft’s third chief executive, Satya Nadella, brought a new slogan to his big job: Mobile first, cloud first. Those four words represent a revolution for Microsoft, because mobile and cloud computing are two areas where the company does not own the standards, does not dominate, and can’t dominate anytime soon. After more than two years as CEO, Nadella knows that Microsoft’s global market share in mobile phones still hovers just below 1 percent, compared with Android’s 84 percent and Apple’s 15 percent. Microsoft’s cloud market share is around 10 percent, Amazon’s 30 percent. Who’s the 800-pound gorilla now?

Even though it’s having to play catch-up for the first time in decades, compelling Nadella to make Microsoft's largest acquisition ever (LinkedIn at $26 billion), things aren’t so bad, at least in the short term. Windows 10 (the most recent version of the company’s venerable operating system) is now running on more than 300 million devices. Microsoft’s leaders may not be happy about their share of the mobile and cloud markets, but the numbers don’t completely capture their business. While Microsoft’s market share in phones is tiny, its mobile revenue is bigger than you’d guess, primarily because it owns so many patents on mobile technology. Google gives away the Android operating system for free, but Microsoft has been very successful at getting Android hardware makers such as Samsung and HTC to pay licensing fees to Microsoft of around $5 for every Android phone and tablet they sell. Samsung alone pays Microsoft more than $1 billion per year.

While Microsoft doesn’t control an overall mobile phone standard, it does control what it says are a few important substandards, including Active Directory, now called Azure Active Directory after Microsoft’s Azure cloud computing service. In an era when personal identities are being stolen by the millions and digital files breached every day, Active Directory is Microsoft’s key to personal and corporate privacy. It is simple but complex: an entry-point identity management system for users of everything from Office 365 to Hotmail to Xbox games to a corporate network. If Microsoft has its way, Active Directory will be used to access iPhones and Android phones as well. “It’s part of our customer obsession, which I’ll admit is something new,” says Microsoft’s chief marketing officer, Chris Capossela. Active Directory is inside Azure, but it is also sold as a separate product. Ballmer would have made companies buy Azure services to get Active Directory, but Nadella sees that as too limiting.

Microsoft is also pushing its traditional productivity applications into the cloud. Office 365, released in 2011, works not only on Microsoft’s own Surface tablets but also on Apple’s iPad. Office 365 has more than 20 million paying personal users, 79 percent more than a year ago. If Microsoft holds your data—data that you create with Office 365—the old Microsoft would have held that data hostage in Microsoft’s cloud storage service. The company would have seen your data as something that it owned. But the new strategy, according to Capossela, is to avoid pushing away users who already use other services, so Office 365 works now with Dropbox, Box, and even Google Drive cloud storage.

Amazon Web Services is still the leader in cloud computing. But Microsoft contends that its cloud offerings are better tailored to the needs of large companies. For example, Azure charges by the minute to suit companies whose employees are using Outlook or Office online. (Nonetheless, non-startups such as General Electric use Amazon’s cloud.)

Microsoft’s great bet for the “mobile first, cloud first” strategy is Continuum, which the company hopes will spur the manufacture of a new class of hardware and accessories. Continuum assumes that if the center of computing has shifted from the PC to the phone, then our phones should run all the peripheral parts of a personal computer. Continuum phones, the first of which will be introduced at the end of this summer, can function like a tablet or a notebook computer, working with a keyboard and monitor. The processing is in the phone, while the data and applications run in the cloud. It’s a clever idea, but any new platform becomes a success only if a software ecosystem grows up around it.

If there’s a piece missing from Microsoft’s cloud strategy and Continuum, it’s support for the legacy applications of Windows, software that in some cases predates the Internet. There are hundreds of thousands of such applications, from software companies and corporate developers alike, that won’t run as-is in the Microsoft cloud or on mobile devices. Microsoft says these programs, which pretty much keep corporate America operating, have to be rewritten for the Azure platform, a process that can take months and costs money.

Other companies are willing to fill the gap. Frame, a startup based in San Mateo, California, promises to have any Windows application running in a virtual machine in the cloud in 15 minutes, making it usable from any phone, tablet, or PC. For what it’s worth, those Frame apps have been running mainly on the Amazon cloud, not Azure.

The old Microsoft liked to control markets by dictating what systems and services it would support. Nadella’s Microsoft wants to defend the technologies it still controls by offering them everywhere.

For evidence, consider Microsoft’s announcement of a new version of its SQL Server database for the Linux operating system. That will be a big deal. SQL Server is a networked database software system that competes with offerings from Oracle and IBM. You could run business processes such as accounting or inventory on any of them, but SQL Server is less expensive. In the past, choosing SQL Server meant choosing Windows as the underlying operating system, which many businesses were reluctant to do, because Linux was generally seen as the superior server operating system. But at -Nadella’s Microsoft, SQL Server is no longer inextricably linked to Windows. SQL Server on Linux will compete head to head with Oracle and IBM, while presumably retaining its price advantage.

This could force Oracle to lower its server prices. When Oracle cuts prices, IBM cuts prices, too. The likely result is chaos in the $40 billion database market—chaos that will only benefit customers. This is a brilliant, bold move that probably wouldn’t have occurred to Steve Ballmer or Bill Gates, who always imagined Microsoft applications running on Microsoft operating systems.

Evidently the thrill of combat is not entirely gone at Microsoft.

Advertisement