Intelligent Machines

Agile Robots

Computer scientists have created machines that have the balance and agility to walk and run across rough and uneven terrain, making them far more useful in navigating human environments.

Walking is an extraordinary feat of biomechanical engineering. Every step requires balance and the ability to adapt to instability in a split second. It requires quickly adjusting where your foot will land and calculating how much force to apply to change direction suddenly. No wonder, then, that until now robots have not been very good at it.

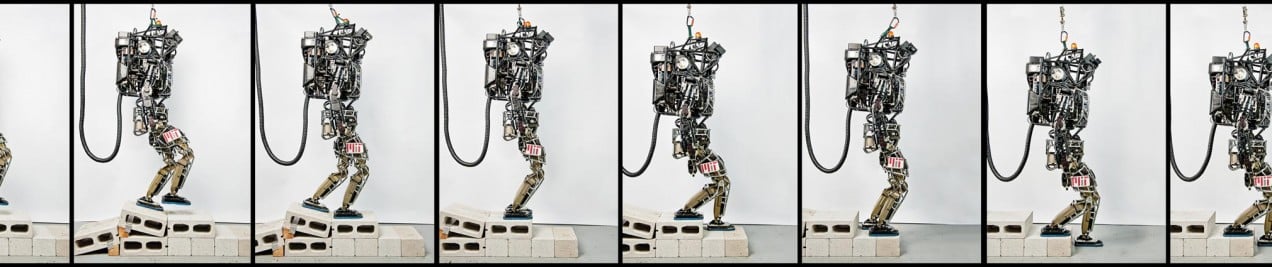

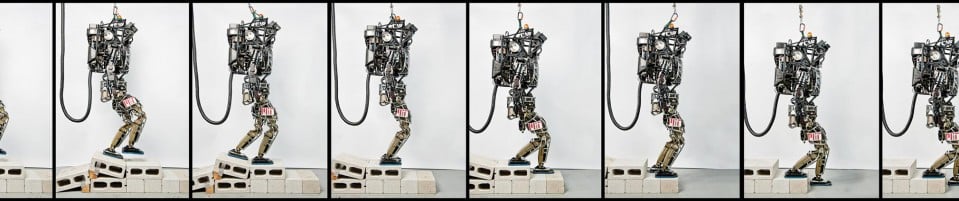

Meet Atlas, a humanoid robot created by Boston Dynamics, a company that Google acquired in December 2013. It can walk across rough terrain and even run on flat ground. Although previous robots such as Honda’s ASIMO and Sony’s diminutive QRIO are able to walk, they cannot quickly adjust their balance; as a result, they are often awkward, and limited in practical value. Atlas, which has an exceptional sense of balance and can stabilize itself with ease, demonstrates the abilities that robots will need to move around human environments safely and easily.

Robots that walk properly could eventually find far greater use in emergency rescue operations. They could also play a role in routine jobs such as helping elderly or physically disabled people with chores and daily tasks in the home.

Marc Raibert, cofounder of Boston Dynamics, pioneered machines with “dynamic balance”—the use of continual motion to stay upright—in the early 1980s. As a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, he built a one-legged robot that leaped around his lab like a pogo stick possessed, calculating with each jump how to reposition its leg and its body, and how aggressively to push itself off the ground with its next bound. Atlas demonstrates dynamic balance as well, using high-powered hydraulics to move its body in a way that keeps it steady. The robot can walk across an unsteady pile of debris, walk briskly on a treadmill, and stay balanced on one leg when whacked with a 20-pound wrecking ball. Just as you instinctively catch yourself when pushed, shifting your weight and repositioning your legs to keep from falling over, Atlas can sense its own instability and respond quickly enough to right itself. The possibilities opened up by its humanlike mobility surely impressed Google. Though it’s not clear why the company is acquiring robotics businesses, it bought seven others last year, including ones specializing in vision and manipulation.

Atlas isn’t ready to take on home or office chores: its powerful diesel engine is external and noisy, and its titanium limbs thrash around dangerously. But the robot could perform repair work in environments too dangerous for emergency workers to enter, such as the control room of a nuclear power plant on the brink of a meltdown. “If your goals are to make something that’s the equivalent of a person, we have a ways to go,” Raibert says. But as it gets up and running, Atlas won’t be a bad example to chase after.

—Will Knight