Intelligent Machines

Breaking Down Walls of Sound

By altering the craft of how music is recorded, technology is actually renewing the social, ephemeral aspects that are experienced most fully in live performance.

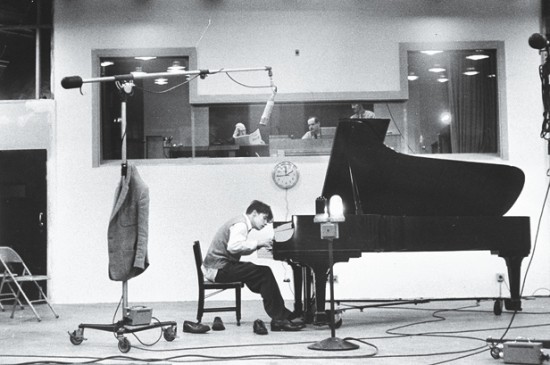

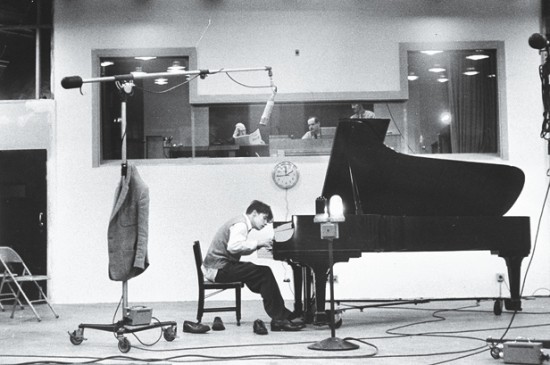

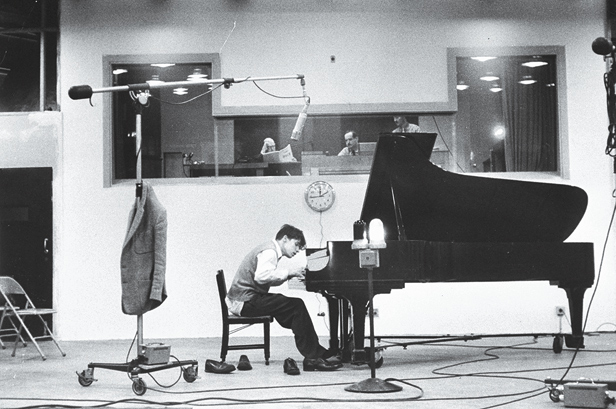

Since the invention of the phonograph 135 years ago, no performer has gone further than Glenn Gould to embrace music’s transition from something ephemeral and experienced socially (whether in a forest clearing, chamber, or concert hall) to something recorded and experienced privately (whether on tape, CD, or MP3). Gould, the pianist best known for his mastery of Bach, was deeply uncomfortable with performing and quit it altogether in 1964, at 32. To him, the audience had become a kind of enemy that listened to see if it could spot mistakes. “The concert is dead,” he declared. He turned, instead, to the purity of recording technology, because it offered full control over how a piece of music would be experienced. He would do take after take of Bach’s French Suites or Goldberg Variations in search of the definitive, if spliced-together, rendering of his interpretation (which was necessarily subjective, as Bach lacked the modern piano).

Gould, who died in 1982, was right that technology would transform the experience of music—just not in ways he could have foreseen. Technology does allow musicians to set down their idea of a perfect rendering, as Gould wanted. But as David Byrne, frontman for the 1970s and 1980s band Talking Heads, observes in his book How Music Works, technology is now making it possible for essentially anybody to make music and distribute it anywhere. Through this democratizing transformation, the value of a recording actually could be diminishing. Technology may in fact be making music a more, not less, social experience: it brings us back together to hear it played live.

Fear of Music

Gould was a hypochondriac who loathed to be touched, but his preference for recording was not as unusual as his personal habits. After his pronouncement, many musicians enjoyed a fertile period of innovation in record production. Just three years after his retirement from the stage, another act that had also quit touring finished a new album: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Released in 1967, it represented a huge technological leap. The Beatles and producer George Martin created a sort of virtual multitrack recorder by chaining four-track recording devices together (mixing down four tracks onto one track of another machine); made speed changes to voice tracks; added analog effects to instrument tracks; and doubled or tripled certain layers of sound. The Beatles never performed it live.

Soon after, the first digital synthesizers appeared. The 1970s and 1980s ushered in an era of specialized digital hardware, epitomized by the $200,000-plus Synclavier, one of the first products that allowed full digital manipulation, synthesis, and editing of sound. Talking Heads was one band to take advantage of such tools. The group started as a spare, arty group at the New York City club CBGB. But with their third album, Fear of Music, they reached a new level of critical and commercial success. This was thanks partly to the production by Brian Eno, the former Roxy Music keyboardist who used more sound effects and processed instrument tracks than the group had done earlier.

Byrne then faced the tricky task of meeting audience expectations. He recalls loading the stage with new gear, including a Prophet-5 synthesizer, but recognizing the limits of the technology. “We could reproduce some of the more far-out studio sounds and arrangements we’d worked on, if only just, but we knew it was equally important to maintain our tight rhythmic core,” he writes. “We were still a live performing band and not simply a group that faithfully reproduced recordings.” Byrne didn’t see his job as just making a recording, or playing a certain version live, but also as celebrating the social aspect of music. Still, back then the recording was still the way most people would experience Talking Heads. The fact was, record sales were where artists like Byrne made money. Touring had a business objective: to drive up interest in the record.

Game Changer

That model persisted for 20 more years; CD sales peaked in 1999. But they soon crashed with the advent of digital file sharing. U.S. music sales in 2011, including digital downloads, totaled $7 billion, down from $14.6 billion in 1999.

Even as recording sales plunged, once-exotic technology for music making got cheaper and cheaper, and fell into the hands of more and more musicians. New software started doing what the Synclavier did. Garage Band, a music recording program that comes free with any MacBook Pro, includes sounds as good as those on once-cutting-edge gear such as the Kurzweil 1000 PX Professional Expander, a black box that musicians bought in the late ’80s to play sampled instrument sounds from a separate keyboard. Websites like Samplebank allow artists to upload and swap samples and riffs for $99. The costs of mixing and recording plunged, and “now an album can be made on the same laptop you use to check e-mail,” Byrne writes. He now works mostly in his home studio.

This made it far easier for musicians to get started. In 2005 Jonathan Coulton quit his job writing software and devoted himself to composing and recording catchy songs about suburbia, the workplace, and geek culture (“Shop Vac,” “Code Monkey”). Coulton is known as a deft Internet marketer, but he credits technology more fundamentally—for helping him make the jump in the first place, and then for helping him craft his songs. “At some point the technology was so advanced that the demos I was making at home were as good as the final recording,” he says. “So why would I make a demo? Why don’t I just sell this?” He gets some ideas from the Kaossilator, a touchpad-controlled synthesizer that costs just $160. A swipe of your finger suggests scales, chord progressions, or drum fills. “In my phone, I have more power than the Beatles had when they made Sgt. Pepper,” he says. “That is a real game changer, and I think we’ve really just scratched the surface.”

Social Roots

There is a corollary to all these advances. With so much more music being made and consumed, it’s harder for musicians to stand out. Who Kill, by Tune-Yards, won many critical plaudits as one of 2011’s best albums. But compared with past critics’ favorites, including Sgt. Pepper and Fear of Music, it barely sold: just 47,000 copies in 2011. This is why live performing—about the only thing, along with T-shirts, that can’t be digitized—has become a musician’s primary source of income.

Byrne remarks that the technology of music consumption—iPods and earbuds—hasn’t actually changed what’s been written. “If there has been a compositional response to MP3s and private listening I’ve yet to hear it,” he writes. Instead, the more powerful force in musicians’ lives is how technology is renewing the emphasis on music’s social roots. Byrne, 60, says he’s getting rid of LPs and CDs and venturing out of his Manhattan apartment weekly to see live acts. “There are other people there,” he writes. “Often there is beer, too.”

He sees the possibility that technology will increasingly bring us out to hear live music, turning Gould’s ideas on their head. “A century of technological innovation and the digitization of music has inadvertently had the effect of emphasizing its social function,” he writes. “Not only do we still give friends copies of music that excites us, but increasingly we have come to value the social aspect of a live performance more than we used to . . . The technology is useful and convenient, but it has, in the end, reduced its own value and increased the value of the things it has never been able to capture or reproduce.”

As for Gould, it’s still possible to watch him today, hunched over his keyboard. He’s immortalized on YouTube, and watching him there inspired me to take a stab at the third movement of Bach’s Italian Concerto. Gould would surely have found himself in strange company online. I hope he wouldn’t have felt his devotion to technology was misplaced.

David Talbot is the chief correspondent of MIT Technology Review.