Business Impact

These Robots Install Solar Panels

Reducing labor costs could help make solar power more affordable.

As the price of solar panels has plummeted, the amount of solar power being generated worldwide is soaring. Yet solar still accounts for less than 2 percent of the world’s total electricity capacity. And small wonder. Each square meter of solar panel generates around 145 watts of electrical power, enough to turn on just two or three light bulbs.

That means you’d have to cover the National Mall in Washington, D.C. five or six times over to match the peak capacity of a large fossil-fuel power plant. What’s more, every one of those panels needs to be installed by hand.

Now companies such as PV Kraftwerker and Gehrlicher in Germany are developing mobile robots that can automatically install ground-mounted solar panels day and night, in all sorts of weather. PV Kraftwerker’s robot is designed to assemble power-plant-grade solar panels, which are four times the size of the ones you’d see on a home.

The main idea is to save money on labor, which accounts for a growing fraction of the cost of solar power as panels get cheaper. According to PV Kraftwerker, a construction firm specializing in solar parks, installations that used to require 35 workers can now be done with just three workers in an eighth the time.

For a 14-megawatt solar plant, the company estimates, it might cost about $2 million to install the panels manually. Using the robot could cut that cost by nearly half. The company says that the robot, which lists for $900,000, could pay for itself in less than a year of steady use.

Robotic help could be a plus given Germany’s ambitious plans to get a third of its electricity from renewable sources within eight years and 80 percent by 2050 (see “The Great German Energy Experiment”). Germany led the world in solar installations in 2011, putting up panels capable of generating around 7.5 gigawatts and covering an estimated 50 square kilometers of ground and rooftops.

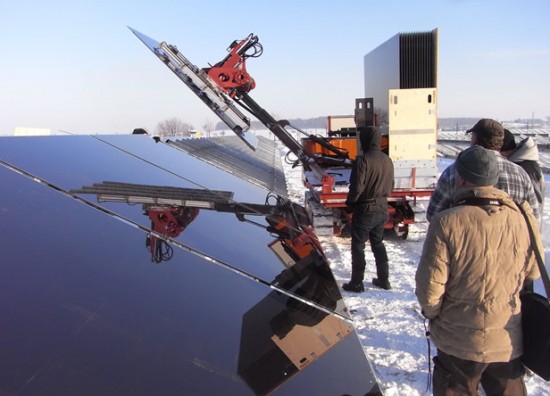

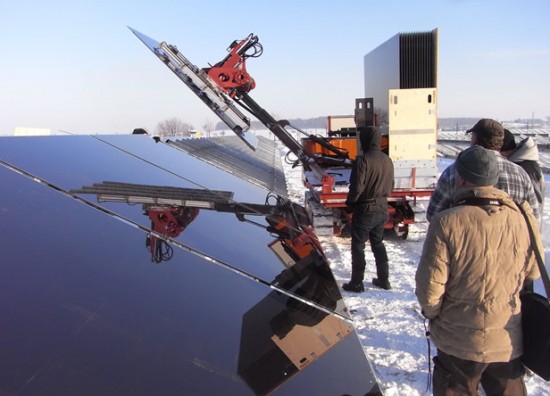

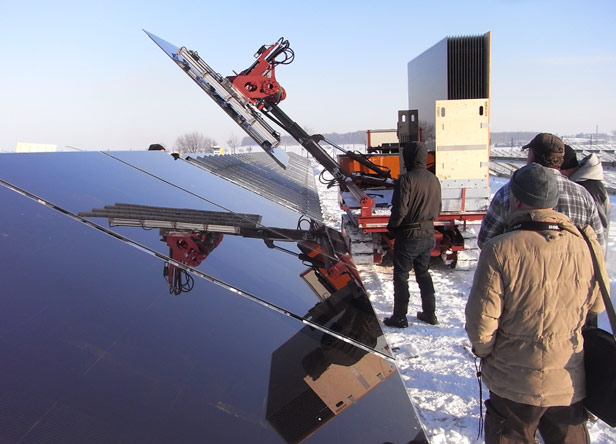

PV Kraftwerker built its robot from off-the-shelf Japanese components. The machinery consists of a robotic arm mounted on an all-terrain vehicle with tanklike tracks. Suction cups grip the glass face of the solar panels and the arm swings them into place, guided by cameras that give the robot a three-dimensional view of the scene.

The robot’s limitations give a glimpse of how hard it’s going to be to completely automate the installation process. Much solar power in Germany is generated by rooftop arrays, but the shape and orientation of roofs is too varied for robots to handle. Even for small solar farms and those using ordinary-size panels, human workers are both faster and cheaper than the robot, says Markus Gattenlöhner, head of marketing at PV Kraftwerker.

Christian Hoepfner, a scientific director at the Fraunhofer Center for Sustainable Energy Systems (see “Redesigning Solar Power”), agrees that the role of robots will be limited. “But I can see the beauty of it for large, ground-mounted installations,” he says. “When you think of huge fields covered with identical panels, you think, ‘Why not have a robot do it?’ As the size of installations increases, it’s unavoidable.”

So far, the PV Kraftwerker robot can only do one thing: lay panels on a metal frame that humans have already installed. Two people walking along beside the robot screw the panels to the frame and make electrical connections.

Yet robotic installation may become more common as other components get adapted to automation. PV Kraftwerker and other companies are also developing robots that, guided by GPS, can pound poles into the ground and then mount panels on them, eliminating the need for workers to install frames. Newer solar modules can be snapped or glued into position instead of being screwed in. Special plugs could even allow robots to make the electrical connections (see “New Solar Panel Designs Make Installation Cheaper”).

Robots like these could be useful in bringing electricity to inhospitable environments. The government of Japan commissioned PV Kraftwerker to develop a version of its robot that could install a solar power plant largely on its own in radioactive areas near the site of the Fukushima nuclear-plant disaster. Gattenlöhner says the Japanese government wants the robot within six months.