People Power 2.0

How civilians helped win the Libyan information war.

After weeks of skirmishes in the Nafusa Mountains southwest of Tripoli, Sifaw Twawa and his brigade of freedom fighters are at a standstill. It’s a mid-April night in 2011, and Twawa’s men are frightened. Lightly armed and hidden only by trees, they are a stone’s throw from one of four Grad 122-millimeter multiple-rocket launchers laying down a barrage on Yefren, their besieged hometown. These weapons can fire up to 40 unguided rockets in 20 seconds. Each round carries a high-explosive fragmentation warhead weighing 40 pounds. They urgently need to know how to deal with this, or they will have to pull back. Twawa’s cell phone rings.

Two friends are on the line, via a Skype conference call. Nureddin Ashammakhi is in Finland, where he heads a research team developing biomaterials technology, and Khalid Hatashe, a medical doctor, is in the United Kingdom. The Qaddafi regime trained Hatashe on Grads during his compulsory military service. He explains that Twawa’s katiba—brigade—is well short of the Grad’s minimum range: at this distance, any rockets fired would shoot past them. Hatashe adds that the launcher can be triggered from several hundred feet away using an electric cable, so the enemy may not be in or near the launch vehicle. Twawa’s men successfully attack the Grad—all because two civilians briefed their leader, over Skype, in a battlefield a continent away.

Indeed, civilians have “rushed the field,” says David Kilcullen, author of The Accidental Guerrilla, a renowned expert on counterinsurgency and a former special advisor to General David Petraeus during the Iraq War. Their communications can now directly affect a military operation’s dynamics. “Information networks,” he says, “will define the future of conflicts.” That future started unfurling when Libyan networks—and a long list of global activists—began an information war against Qaddafi. Thousands of civilians took part, but one of the most important was a man who, to paraphrase Woodrow Wilson, used not only all the brains he had but all the brains he could borrow.

MO BETTER

The war against Qaddafi was fought with global brains, NATO brawn, and Libyan blood. But it took brains and blood to get the brawn. On February 18, three days into the protests that would swell into the successful revolt against the regime, Libya went offline. Internet and cell-phone access was cut or unreliable for the duration, and people used whatever limited connections they could. In Benghazi, Mohammed “Mo” Nabbous realized he had the knowledge and the equipment, from an ISP business he had owned, to lash together a satellite Internet uplink. With supporters shielding his body from potential snipers, Nabbous set up dishes, and nine live webcams, for his online TV channel Libya Alhurra (“Libya the Free”), running 24/7 on Livestream.

Nabbous had pitched a brightly lit virtual tent in a darkening Libya. As Benghazi descended into fighting that killed hundreds and left thousands injured, he gave interviews to international media outlets such as CNN and the BBC. He also connected with supporters and activists from dozens of countries, among whom a cadre of information warriors soon emerged.

Stephanie Lamy was one. A self-described strategic communications consultant and single mother living in Paris, she was using the Egyptian and Libyan revolutions to explain her work to her nine-year-old daughter. They searched Google and found Libya Alhurra TV; Lamy was hooked. “When I saw the cries for help on Livestream, I knew my skills were just perfect for this situation, and it was my duty to help,” she says. She abandoned her business and started working up to 24 hours a day. It was a situation where “each action counted.”

In its first six weeks, the channel served 25 million “viewer minutes” to more than 452,000 unique viewers. Nabbous had only enough bandwidth to broadcast, so volunteers stepped forward to capture and upload video. Livestream took an active role, too: it archived backups several times a day, dedicated a security team to guard against hackers, and waived its fees. Others ran Facebook groups or monitored Twitter, pasting tweets and links into the chat box. They shared first-aid information in Arabic and transcribed or roughly translated interviews in close to real time. “All of us were on a fast learning curve,” says Lamy. “Tanks were moving in, people were getting shelled, people were getting massacred.”

On March 19, Qaddafi launched an assault on Benghazi. With shells exploding, Nabbous said, “No one is going to believe what they are going to see right now!” before heading out to report live. He was still broadcasting when a sniper shot him. Hours after Nabbous’s death, French fighter jets strafed the heavy armor attacking Benghazi. His widow, Samra Naas, pregnant with their first child, broadcast in his place: “What he started has got to go on, no matter what happens.” Along with friends and family, three women she had never met spent much of the night comforting her, as best they could, over Skype.

THE HIT LIST

Among them was Charlie Farah, a Lebanese-American radio producer. She arranged technical support for Libya Alhurra TV, as well as two-way satellite subscriptions for freedom fighters. That required their trust. “When someone you’ve never met says they’ll pay for your satellite, they get your GPS coördinates,” she points out. “In the wrong hands, a missile could follow.”

Most freedom fighters were civilians with no first-aid or weapons training. Farah started teaching what she could about basic triage, planning escape routes, and how to fire and move. She showed people how to share files using YouSendIt, because guards at regime checkpoints were now searching for information being smuggled on portable media. (Rebels in Sabratha had hidden thumb drives in their hair; weapons were slung under their sheep.) For the fighters, discovery could mean imprisonment, torture, or execution.

Although those in Libya were most at risk, Qaddafi had a grim reputation for lashing out overseas. In addition to his involvement in the Berlin nightclub bombing of 1986 and the explosion of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988, he supported a bizarre collection of terrorist groups and hunted individual dissidents. In the 1980s, he had dozens assassinated around the world.

Mustafa Abushagur, who opposed the regime for decades, managed to escape that fate. A microsystems engineer and entrepreneur, he was the founding president of Dubai RIT (Rochester Institute of Technology). In 1980, he was doing graduate study at Caltech when the FBI visited and warned him: “Listen, you’re on a hit list.” He started wearing cotton gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints when packing and mailing anti-Qaddafi magazines. When the revolution began, he used Facebook to keep abreast of fast-changing events and ultimately returned to Libya, where he is now interim deputy prime minister. “The information war,” he says, “is what made the revolution succeed.”

THE COUSINATE

Some information warriors set up their own operations. For Rida Benfayed, an orthopedic surgeon then based in Denver, getting online was the first priority when he reached his hometown of Tobruk, 290 miles east of Benghazi. Benfayed got hold of the city’s only two-way satellite Internet connection and started accepting hundreds of requests to connect on Skype. He organized his contacts into six categories: English media, Arabic media, medical, ground information, politicians, and intelligence. His contacts included ambassadors and doctors, journalists and freedom fighters. A source of high-grade military intelligence soon turned his ad hoc operation into a control room.

Someone who claimed to be a retired European intelligence officer contacted Stephanie Lamy. The detailed intelligence he sent appeared authentic: it included the number, location, and movements of Qaddafi’s troops and heavy weapons. There were even updates as the regime’s long armored column approached Benghazi. Lamy passed the intelligence on to Benfayed, who shared it with Mustafa Abdul Jalil, the Libyan justice minister who had defected to become chair of the National Transitional Council (NTC) and the opposition’s de facto leader. (Today, he is the official leader of Libya’s interim government.)

For a few weeks during the period before NATO recognized the NTC, and before the source disappeared as suddenly as he had surfaced, he was a mother lode of military intelligence. He revealed that the regime’s standard operating procedure was to cut an area’s cell-phone coverage three days before an attack; suggested strategic plans to protect Benghazi if the U.N. Security Council didn’t act; and explained how and where to attack the regime’s tanks. With Jalil’s blessing, Benfayed set up ground information links with the front lines and expanded his team to around 30 people, including opposition army, navy, and air force officers; internal and foreign media liaisons; and medical and IT specialists. The room was soon taking in so much live local information that one delighted visitor said, “It’s just like Al Jazeera!”

When the opposition smuggled weapons and humanitarian aid into Misrata’s port, which was being heavily shelled by the regime, Benfayed gave NATO the time of the run, and the size and name of each boat, to reduce the chance of friendly fire. Benfayed ran his control room until he was confident he had directly linked NATO to the key leaders in each of his networks.

Libya’s six million or so people are concentrated in a coastal belt of cities and connected in a kind of “cousinate” of extensive personal and family networks. The trust embedded in these networks was valuable to the opposition: a cousin’s cousin could check bona fides, or a friend’s cousin could supply intelligence from within the regime’s security apparatus. Meanwhile, Qaddafi’s brittle hierarchy, absorbed in the kind of capricious and despotic interventions dubbed “sultanism,” was isolated from this social structure and plagued by distrust.

Libyans lived in fear of their sultan for over four decades, but their tight social networks proved highly resilient when the delusion that people believed in the regime—what Kilcullen calls “the presumed consensus”—fell away. At that point, the cousinate took on the sultanists.

MISRATA CALLING

Gihan Badi, a U.K.-based architect, remembers overcoming that fear. Before the uprising, she was scared: though she knew that protests were planned for February 17, she deleted any talk of them from her Facebook group for Libyans. On February 15, in a call to family in Benghazi, she learned that the protests had, unexpectedly, already started. Using a kind of pseudonym, Juhaina Mustafa, she rang Al Jazeera Mubasher, the network’s live phone-in channel, to share the news. Thanks to a connection established through her brother, she arranged interviews for Nabbous with Al Jazeera and the BBC. She began giving journalists the numbers of dozens of people in Libya, making sure to verify the trustworthiness of contacts she did not personally know. Truthful and reliable information mattered, she says, not least because “we are not faking things anymore.”

“Juhaina Mustafa” was denounced on Libyan state TV. Worried about the security of her own phone, she bought batches of prepaid phone cards. She discovered a useful rule of thumb: Qaddafi stooges making repeated Skype requests to connect with her had short fuses. “For the first three messages they are nice,” she says. “Then on the fourth they become angry and start saying, ‘We will kill you! We know who you are!’” Other contacts were patient, realizing how busy she must be. A working mother, she was now even busier and focused on a new emergency: Misrata.

Libya’s third-largest city, strategically located between Tripoli and Benghazi, was besieged. For months, heavy artillery and tanks pounded Misrata from outside. Inside, dozens of snipers—including female mercenaries from Colombia—dominated the city center. “There were dead bodies in the streets, unrecoverable because of the snipers,” says Marwan Tanton, a citizen journalist with Freedom Group Misrata, a group of students turned reporters, carrying cameras and guns. “Dogs were eating them.”

Stephanie Lamy, Rida Benfayed, and Badi’s husband, Nagi Idris, were among many scrambling to get humanitarian supplies to Misrata and to alert the world to an unfolding disaster. They worked to smuggle in by sea the first international journalists, including Fred Pleitgen of CNN. (They played a similar role for the hitherto underreported fighting in the Nafusa Mountains.)

Identifying weapons was another urgent task in Misrata, as elsewhere. Andy Carvin of NPR (a member of the 2005 TR35) used Twitter to crowdsource weapons knowledge. It took his followers just under 40 minutes to identify unusual Chinese parachute land mines found in Misrata’s port area—their first known use in the war (an extraordinary event preserved on Storify).

As with Wikipedia, such expertise might come from anyone—like Steen Kirby, a high-school student in the state of Georgia. As well as identifying weaponry, Kirby pulled together a group through Twitter to quickly produce English and Arabic guides to using an AK47, building makeshift Grad artillery shelters, and handling mines and unexploded ordnance, as well as detailed medical handbooks for use in the field. These were shared with freedom fighters in Tripoli, Misrata, and the Nafusa Mountains.

The Misratans showed impressive ingenuity. Engineers hacked new weapons—including a remote-controlled machine gun mounted on a children’s toy—and adapted technology on the fly. Laptops, Google Earth on CD-ROMs, and iPhone compasses gave the freedom fighters range. After a rocket was fired, a spotter confirmed the hit, reporting that it had landed, for example, “30 yards from the restaurant.” They then calculated the precise distance on Google Earth and used the compass, along with angle and distance tables, to make adjustments.

Freedom Group Misrata had compelling video but limited signal strength. The citizen journalists fixed this by bridging pairs of mobile Internet dongles to share their increasingly professional content (marked with their logo).

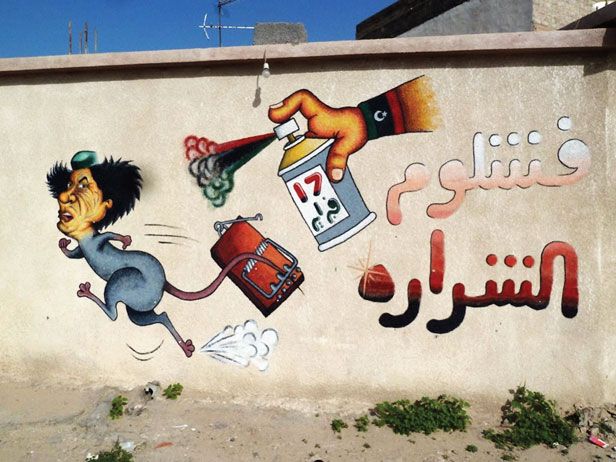

After 40 years of silence, Libya is talking again. The most noticeable thing about the country’s urban landscape today is the graffiti on almost every wall. War stories are frequently shared by photo and video over ubiquitous camera phones and computers. While many are too horrific for mainstream media, they circulate widely on YouTube and Facebook. A clip on a mercenary’s captured cell phone revealed the killing of 37 people in the Nafusa Mountains. But other videos, taken on mobile devices inside the country, were widely broadcast on Western television. Knowledge within the U.N. Security Council of atrocities in Libya had a powerful influence on its members’ vote on the no-fly zone. That vote brought the brawn into the equation.

THE BRAWN

UNSC Resolution 1973 resulted in nearly immediate operations by several nations, led by the United States, before they handed control to NATO’s Operation Unified Protector (OUP). A naval blockade used surface ships and submarines from 12 countries, while air power came from NATO and 15 countries—including Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan. In 222 days, some 26,000 sorties were flown, with more than 9,600 strike missions hitting about 6,000 targets.

For weeks, the Libya Alhurra network tracked strikes via a live air traffic control feed from Malta. David Cenciotti, a military aviation blogger, notes that traffic entering Libyan airspace would identify itself, for example, as a Predator drone “going tactical”—switching radio frequencies to contact the tactical control unit. Strike confirmations, recalls Stephanie Lamy, emerged on Twitter “in about six to eight minutes, on average.” NATO says it took “one or two minutes” for the initial confirmation of a strike, although it had a singular advantage: the “Air Tasking Order” showing where and when each aircraft was due to strike.

This was a rare example of unofficial NATO information reaching civilian networks. The reverse was more common: civilians sent information to NATO, which had discreetly sought out key information, including multiple independent sources and precise coördinates. This communication was very much one-way; there was little attempt at relationship building with the new breed of technologically adept and highly networked activists.

Publicly, NATO and its secretary general, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, do use social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and a video blog—albeit as an adjunct to standard press-office fare. They took the trouble to ensure that the first announcement of the end of the Libyan operation came via Twitter and Facebook. Further, in one press briefing, NATO explained that its “fusion center” used open-source information like Twitter to deliver “usable intelligence.” Less publicly, the story is somewhat different.

THE INSIDER

The experience of an active French navy officer, who spoke to Technology Review on condition of anonymity, suggests a high degree of wariness in the military about social media and Web communities. The officer, whom I will call Eric Martin, is an expert in combat systems and tactical data links—used by NATO and the United States in command, control, and communications. Before being assigned to join the naval operation, he had become intrigued by the high level of “open-source intelligence” to be found on social media.

After about a hundred hours of work, Martin had 250 or so direct contacts in Libya and elsewhere. He created, in effect, a private intelligence network. Initially, he expected only “ambient” or background information, but the intelligence he gathered soon proved useful for both strategy and tactics. He tried alerting his hierarchy to its potential for following the flow of action on the ground. It took a while for them to accept this. “They were very afraid in the beginning, because they had no control,” he says, “[so] I ran a kind of laboratory.” He set up a desk and was given no military intelligence. His captain asked specific questions and matched Martin’s performance against more formal intelligence channels. Precise comparison is difficult, but Martin estimates that eventually 80 percent of the intelligence used by his vessel came from his sources.

Martin believes that the U.S. and U.K. use software to analyze social media, which he assumes provided input during the Libyan conflict. Indeed, the CIA already tracks social media, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which funded the development of the Internet, is currently exploring these channels. If countries can learn to exchange such information at the right level, at the right time, it might be possible to avoid tragic errors, Martin believes. But he asks: “Is NATO able to make the right evolution, with the right software, with the right time line? I don’t think so.”

Martin sees several problems. NATO is a complex coalition riddled with cultural and linguistic barriers, social media are not appreciated or well understood by its leaders, and verifying the identities of informal sources takes considerable time. Even so, he is convinced that his unofficial network left him better informed than counterparts relying on official French intelligence channels.

THE REAR ADMIRAL

Charlie Farah is one of many who wish NATO had established a rapport with active nonmilitary networks, or at least key nodes within them. By making targeting more efficient, she believes, this could have reduced casualties, saved money, and possibly shortened the war.

One incident in which better links might have helped came on April 7, when—a week after assuming control of operations—NATO bombed a convoy of tanks and other armor captured by freedom fighters. There were several deaths.

Farah, Lamy, and many others had known for days that the tanks were in freedom fighters’ hands. Whether the incident was due simply to rebels’ being mistaken for pro-Qaddafi forces is somewhat murky. Some sources say that NATO may have been the victim of disinformation supplied by General Abdul Fattah Younes, a senior military defector later assassinated by opposition forces. Others say the freedom fighters had been warned by NATO not to cross a “red line.”

The next day, Rear Admiral Russell Harding, British deputy commander of NATO’s Operation Unified Protector, responded to a reporter’s questions at a press briefing. “I’m not apologizing,” he said. “We had no information that the opposition forces were using tanks.” Asked how NATO was trying to improve communications with the freedom fighters to prevent more such incidents, he was blunt: “It’s not for us to improve communications.”

One NATO official to whom Technology Review spoke did confirm that NATO took advantage of civilian communications coming out of Libya, adding that the organization had never before had this kind of information. However, the role of civilians in providing intelligence, up to and including identifying targets, is an uncomfortable subject for NATO. Alongside a military concern for operations security, there are political sensitivities, given that countries including South Africa, Russia, and China complained that NATO forces were exceeding the mandate to protect civilians. Yet throughout the conflict, civilians did feed intelligence to NATO: in fact, they were asked to.

SOCIAL NETWORK INTELLIGENCE

When NATO called Nagi Idris out of the blue in search of intelligence, he was “very, very scared.” He was a research scientist living in Leeds, England, with his wife, Gihan Badi, and young son; the intelligence world was new to him. His contribution to the Libyan effort had been to gather information about the medical needs of civilians and freedom fighters in Benghazi, Misrata, and the Nafusa Mountains, raise the funds to address those needs, and secure humanitarian supplies and transport. As Libyans, Idris and Badi decided to call the British government to ask whether the NATO caller was a real contact and, if so, whether they should coöperate. It took half an hour for an official to confirm the name and verify that U.K. authorities were happy for them to work with NATO.

Their contact was from NATO’s Civil-Military Co-operation (CIMIC) group, whose website says its task is to “intensify the involvement of civilian actors in a more comprehensive and integrated way into planning.” With her husband concentrating on humanitarian relief, Badi took the lead, supplying regular updates including, at NATO’s request, precise coördinates. Badi knew NATO wanted multiple sources for cross-checking, so she created Chinese walls to separate herself from others—including her husband—who had their own networks.

Another Libyan civilian who contributed important intelligence is a man I will call Asim (he requested anonymity because he believes that his work, providing targeting information to NATO, led directly to the deaths of people who may still have family in Libya). An influential, well-connected Libyan working in the media, Asim smuggled most of his family out of the country and then set up “op rooms” in Tunisia, Dubai, and Spain. “I don’t think any intelligence agency in the world knows Qaddafi as well as the Libyan people,” he says.

Asim’s network of information smugglers brought thumb drives and disks out of Tripoli and got approximately a hundred Thuraya satellite phones into the country. They supplied NATO with blueprints, troop locations and movements, and a detailed diagram of Qaddafi’s family connections. His estimate of Qaddafi troop numbers in Brega, between Benghazi and Misrata, came through a contact in the catering company supplying their meals.

Asim’s op rooms conveyed their intelligence to NATO, he says, via “a super-node in Dubai.” He found himself working with people in all sorts of professions, from video editors to cartographers: he remembers one “girl” he found through Twitter who “would punch in the locations of snipers on Google Maps.” The map was shared online and on the ground.

Like any civil war, this conflict was dynamic, complex, and unpleasant. Watching the combat footage—a blur of street-fighting men, nondescript architecture, gunfire, explosions, and crowds that could be either angry or exultant—it is hard to tell exactly what is happening or where. But, simplifying, what happened is this: once Benghazi was secured at the cost of many uprisings, battles, and skirmishes throughout the country, two spearheads emerged: in Misrata and in the Nafusa Mountains. They were a pincer whose object was Tripoli.

INFORMATION POWER

In Tripoli, Qaddafi created a gilded cage in the opulent Rixos Hotel for the closely chaperoned international media. They had access to the official voice of government, but they distrusted what they were told. Yet from the start, Qaddafi’s communications had been undermined by unofficial sources: by Mo Nabbous and the Libya Alhurra TV network, by students like Freedom Group Misrata, and by the growing number of international journalists in opposition-held areas. On the ground, individuals were also blurring the line between journalism and fighting. Twenty-one-year-old Inas Mohamed, a student of English literature from Yefren, not only smuggled gelignite, an explosive, past Tripoli checkpoints but wrote, printed, shared, and scattered on the street hundreds of samizdat flyers.

Thanks to technology, collaborators could be anywhere. In Finland, as well as helping advise on attacking Grads, Nureddin Ashammakhi set up LibyaHurra.info as a direct response to Qaddafi’s disinformation campaign. A global brigade of volunteers published daily reports from Libya in 10 languages, including Chinese, Russian, and Tamazight (the language of the Berbers, who prefer to be called Amazigh—”free people”). As hundreds of thousands of noncombatants fled Libya, Ashammakhi returned from Finland and joined the much smaller but significant flow of exiles and expats heading in the opposition direction. He set up field hospitals near Yefren to treat the wounded of both sides, and was thus active in both the military and information wars.

Ashammakhi instinctively reaches for technological analogies to capture the complexity of this conflict. He likens those on the ground in the information war to a coöperative network of sensors giving feedback “continuously, dynamically, and in real time.” He compares the way self-organizing civilians come together in support of military operations to CPU scavenging, where spare capacity on individual computers is pooled across a grid. He cites moving examples of people stepping forward to fill a gap: strangers who left breakfast for hungry doctors; Yefren’s council leader, unasked, starting to clean the hospital—a task he quietly continued even on the day after his son was killed. Ashammakhi contrasts this with Qaddafi’s rigid hierarchy, obsessively focused on the leader and ultimately overthrown by a “network of nodes.”

The world’s nodes and networks are multiplying and growing denser: a third of the world’s population is online, and 45 percent of those people are under 25. Cell-phone penetration in the developing world reached 79 percent in 2011. Cisco estimates that by 2015, more people in sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and the Middle East will have mobile Internet access than have electricity at home. Across much of the world, this new information power sits uncomfortably upon archaic layers of corrupt or inefficient governance.

In today’s world, as the U.S. Army Field Manual for Operations notes, “information has become as important as lethal action in determining the outcome of operations.” Now the traditional networks through which information flows—from the mass media to military units—are being rewired. By and large, military and intelligence organizations still see the new networks, and the coöperation and collaboration they engender, as a threat, not an opportunity.

But as military budgets shrink, the world urbanizes, and Kilcullen’s “presumed consensus” collapses, cheap handheld technology is making citizen networks an inevitable feature of the information battle space.

John Pollock is a contributing editor to Technology Review. He wrote about the uses of social media during the Arab Spring in the September/October 2011 issue.