Through a Camera, Darkly

The technology of lenses has made art richer and more meaningful for hundreds of years. A Gerhard Richter retrospective shows Germany’s most famous artist responding to the camera over a lifetime of painting.

Around 1670, Johannes Vermeer of Delft painted a young woman making lace. She can be seen concentrating intently on what she is doing. In the foreground is a sewing cushion, a piece of needlework equipment consisting of a box with a padded textile cover, from which skeins of red and white thread are spilling out onto another surface. Loose, liquid, those fibers resemble to a contemporary eye something of which Vermeer could have had no conception: abstract art. When you look at that lovely festoon of red looping over the blue table cover, Jackson Pollock comes irresistibly to mind.

Last autumn this beautiful, tiny painting (it is slightly more than eight by nine inches) was the centerpiece of a beguiling exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England (“Vermeer’s Women: Secrets and Silence”). I am going to concentrate on a single observation about The Lacemaker: Vermeer must have looked at the model and her surroundings through a lens.

There has always been some academic resistance to this line of thought about Vermeer (perhaps because we want our greatest painters to be supremely skilled draftsmen who do not require any mechanical aid). But even the scholarly authors of the catalogue for the definitive Vermeer exhibition (held in Washington and The Hague in 1995–96) concluded, “The optical effect of the threads certainly derives from a camera obscura image.”

What one sees in The Lacemaker is a great painter making brilliant use of the distortions a lens can cause. The picture is constructed in terms of differing fields of focus. The foreground is fuzzy, but the area in which the woman is absorbed—her fingers, the bobbins, the lace—is absolutely sharp. Her head and shoulders are, again, gently blurred. Vermeer was making art—creatively and innovatively—out of the visual anomalies created by a piece of antique technology, the filmless camera.

Fast-forward 340-odd years to the Tate Modern, in London, where a magnificent retrospective exhibition of the work of Gerhard Richter, titled “Panorama,” pulled large crowds from October to January. (The exhibition is now at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin and will move to the Pompidou Center in Paris.) During the interval between Vermeer and Richter, the camera obscura evolved into the photographic camera, and the photograph became the dominant visual form of our culture.

“Panorama” makes it clear that Richter is among the truly outstanding painters of the last half-century. And going from The Lacemaker to the Richter exhibition revealed to what an extent Richter has worked—like Vermeer in that picture—by using not just the photographic image but also the blurring, smudging, and hazing a lens can create.

Indeed, Richter has said that he wants to paint like Vermeer, whom he has called “the artist-god.” His own works are “a little damaged,” he told the curator Robert Storr, and he means it literally: he was so frustrated by his inability to measure up to Vermeer that he attacked some paintings with a palette knife. “I really want to make beautiful paintings,” he said. “I couldn’t quite hold it; they’re not as beautiful as Vermeer.”

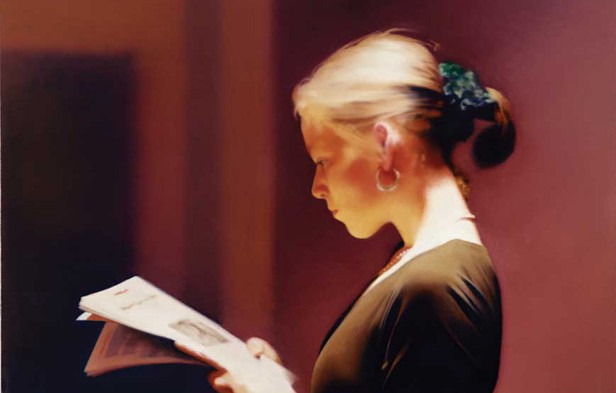

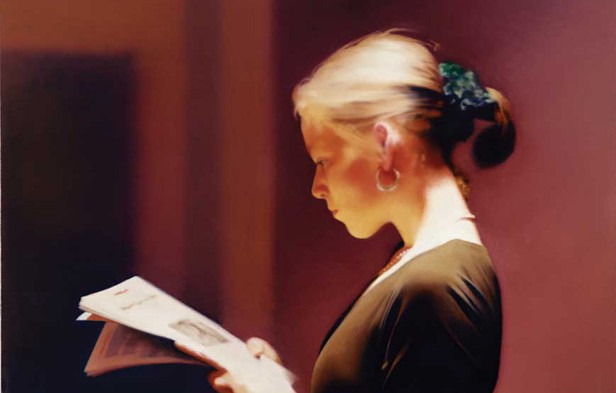

On occasion, he has consciously echoed the Dutch master. Richter’s 1994 painting Reader (Lesende) is an updated version of Vermeer’s Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (c. 1663–64). But there’s much more to the relationship than such occasional visual quotations. As you walk through “Panorama,” you realize that Richter has been endlessly fascinated by the interplay between the sharp, clear image and the visual noise created by the lens—just like Vermeer in The Lacemaker.

PHOTOGRAPHIC MEMORY

Many of Richter’s most characteristic works depend on the way the camera—if it doesn’t quite lie—tends to be “economical with the truth” (as a British civil servant, in the witness box, once described the deliberate lacunae that give a “misleading impression”). Some of the best-known were derived from black-and-white photos, in some cases family snapshots. In the 1965 work Uncle Rudi (Onkel Rudi), the subject stands smiling, wearing a German officer’s uniform from the Nazi era; in Aunt Marianne (Tante Marianne), also from 1965, his aunt holds an infant who seems about to burst into tears.

At first glance, these might seem chilly. Almost all of them are distorted, as if the camera was moving at the moment the shutter clicked; most have zones of out-of-focus fog. But the chill is an illusion, and the blur (achieved by brushing the not-quite-dry paintings with a soft brush) a highly conscious device. When I talked to Richter in 2008, I suggested that the latter was a way of adding distance and detachment to the picture. He denied it: “That’s not what I think about my pictures. I feel they are shameless, they so directly reflect what I am thinking and feeling. I’m not really a cool artist.”

Blurring was there in the original photographs, but it was exaggerated in the paintings for several reasons. One motive was to make it possible to look at the unbearable. Richter’s aunt suffered from mental problems and was forcibly sterilized and then murdered in a Nazi euthanasia program. The child in her portrait is the artist himself.

In a series of 15 photo-paintings Richter did in 1988 about the careers and deaths of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group, the darker the subject matter, the more it is veiled in fuzz and smear. In Hanged (Erhängte), the body of Gudrun Ensslin suspended in her cell seems to be seen through a thick mist; Arrest 1 and Arrest 2 (Festnahme 1 and Festnahme 2), showing Holger Meins being forced to strip naked, are barely legible at all, just masses of sinister gray patches.

The effect of the blur, then, is emotional but also makes a Germanic philosophical point. “Lack of focus is important for me,” Richter once said, “because I cannot see it exactly anyway and do not know it”—“it” being what he is painting. In other words, an image is always partial and maybe misleading. You never really see what Kant called the “thing-in-itself.”

The smear and blurring are also beautiful. They help give the pictures presence as works of art, making them what Richter calls “ansehnlich“—meaning considerable, or worth seeing. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he painted a series based on aerial photographs of cities. One, Townscape Paris (Stadtbild Paris), completed in 1968, was painted in a deliberately loose, free fashion and looks like an abstract work up close. Only at a distance does it resolve into buildings and streets, suggestive of the bombed-out ruins that characterized most German towns in 1945. It is not quite clear that Richter intended that last layer of meaning, though he noticed it later. “My paintings,” he has said, “are smarter than I am.”

RANDOM BEAUTY

Richter’s work generates its own beauties and meanings. A subgenre of his abstract oeuvre is derived in a systematic, mathematical way from color charts. To create the 1974 work 4096 Colors (4096 Farben), he took the primary colors red, yellow, and blue, plus green, mixed 1,024 shades from them, and put those down four times each in neat squares. The energy, even euphoria, of the result is not a feeling expressed by the artist but an automatic effect. Damien Hirst’s spot paintings are generated by a similar system. These works, currently on exhibit in Gagosian Gallery locations worldwide, follow the simple rule that no two colors are repeated in a single picture. The appearance of the result is dictated by the size of the dots and of the canvas. Hirst’s titles are all the names of pharmaceutical products, implying that actual human emotions are chemical in origin, just as the joy of the pictures is created by artifice.

But Richter’s abstract pictures have much more often been loose and what art historians call “painterly.” Some have been made with the aid of a squeegee, a tool for smearing, which is pulled over the work again and again, unpeeling some sections of paint and smudging others. This, too, is a process open to chance. Richter describes it as a succession of yes/no decisions, a process of accepting or rejecting what has happened until the artist is satisfied by the result. Other than that, he is not entirely in control. The paintings can suggest a glimpse of sunlight filtered through leaves, or reflections on water.

Richter has published a monumental album of his photographic sources, entitled Atlas, and he has made whole books of photographs, such as Wald (2008), a little masterpiece consisting of shots of a wood near Cologne. The latter is, like so much of his work, about how randomness—in this case a dense tangle of trunks and twigs—can generate beauty and a sort of order. But even such important works as Wald and Atlas are ancillary to his painting.

“I make a lot of photographs,” Richter told me, “but I am not very interested in photography as an art. They don’t touch me that much.” What affects him most, perhaps, is the Vermeer effect: the interaction between the cool, apparently objective image created by a piece of equipment—a camera—and the free play of paint.

Martin Gayford is chief art critic for Bloomberg News. He reviewed David Hockney’s new video installations in the September/October 2011 issue of Technology Review.