Business Impact

Web Natives Take Aim at Energy

Cleanweb entrepreneurs come armed with computer skills, a profit motive, and a determination to solve environmental problems.

Daniel Rosen wants to make clear that his solar energy startup is not a traditional energy company. “Solar companies used to be about hardware,” says the 26-year-old cofounder and CEO of San Francisco-based Solar Mosaic. “We’re an online marketplace.”

Rosen was among dozens of twentysomethings who congregated at New York University this January for the second “Cleanweb Hackathon”—a weekend forum for would-be entrepreneurs to demonstrate the role that mobile apps, social networks, and Web software can play in improving how we use energy and natural resources.

The term “cleanweb” was coined by San Francisco-based venture capitalist Sunil Paul and is meant to draw a distinction from cleantech, the high-risk, capital-intensive industry led by battery startups, biofuel makers, and makers of wind turbines and solar panels.

The cleanweb, by contrast, is all about using inexpensive information technology to change how the world consumes energy. Paul, an investor with Spring Ventures who has invested in Solar Mosaic and helped organize the hackathon, calls the cleanweb “the most powerful lever” available today to entrepreneurs hoping to solve environmental and ecological challenges.

During the weekend competition, teams set out to show how data available on the Web can help. One group of programmers combined data from New York City’s government with Google Maps to build a website tracking which municipal buildings emit the most greenhouse gases. Another team created a comparison-shopping engine that ranked products sold on Amazon.com according to their energy efficiency.

Worry over the environment, and a desire to challenge the fossil fuel industry, is what is leading some people to join the cleanweb movement. “What’s motivating me is the climate change problem,” says Zak Accuardi, a recent graduate of Columbia University. “People are ignoring it, and I’m trying to figure out the best way I can effect change.”

Because the field is so new, there’s still a chance to strike it rich, promoters promised. Dave Graham, an investor with Greenstart, which runs an incubator in San Francisco for cleanweb startups, told the coffee-swilling hackers that “you don’t have to start the next Facebook to make a boatload of money.”

Rosen helped start Solar Mosaic in 2010 as a way to encourage building owners to install rooftop solar panels. Currently, photovoltaic solar energy still costs more than electricity from fossil fuels. One major reason for that, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, is that about half the expense of a rooftop solar installation is for things other than solar panels—including financing, permitting, manual labor costs, and finding customers.

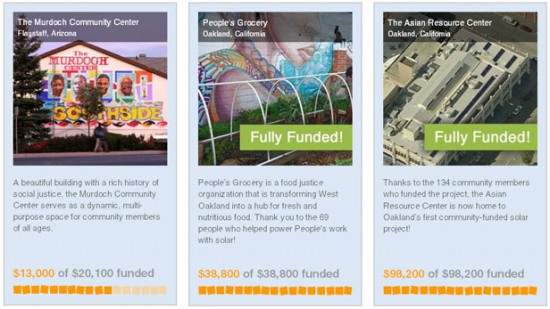

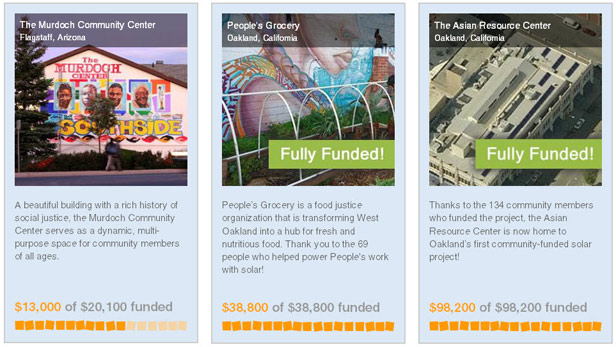

Solar Mosaic came up with the idea of using Internet crowd funding to help defray those costs. Building owners can now use its website to pitch rooftop solar projects to the general public. Visitors to the site buy $100 shares in projects they like; when a funding goal is reached, users’ credit cards are charged and the installation is paid for. Supporters are gradually paid back out of monthly fees charged to building owners (out of which Solar Mosaic takes a commission).

Currently, Solar Mosaic is raising money for three projects, including one to put solar panels on the home of Sonto Begay, a Navajo artist. Of the two projects already funded, one raised $98,200 to install more than 120 solar panels on a building in Oakland, California.

Rosen thinks the cleanweb idea is powerful because it combines “new ways of spreading information with new forms of creating energy.” Over the hacking weekend, Rosen led a team of students that worked on an online map that could help Solar Mosaic’s users locate projects seeking funding and even integrate Twitter conversations about solar power—so people can “see the solar conversation happening,” explains Rosen.

Many cleanweb ideas—such as apps that allow consumers to track and control home electricity use—are only as good as the information that’s available electronically. That can be a major limitation, especially when trying to get information from local utility companies. “It takes a substantial investment in technology and time to integrate with the utilities. It is not fast, and it is not easy,” says Eric Shiflet, a product manager at Tendril, a Boulder, Colorado, company whose software tries to create a “two-way dialogue” between utilities and customers’ appliances and smart thermostats, a concept it calls the Energy Internet.

Tendril is making data on electricity consumption and pricing available through an application programming interface, hoping other programmers will find new ways to use it. Tendril was also a sponsor of the New York programming competition.

“We want to make sure that whoever ends up building the killer energy app is absolutely going to build it on our platform,” says Shiflet.