Business Impact

The Comeback of Xerox PARC

Infamous for failing to commercialize the technologies it invented, Xerox’s R&D subsidiary has a new strategy for innovation: make money.

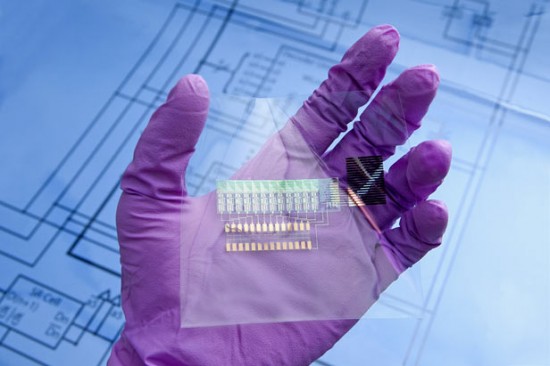

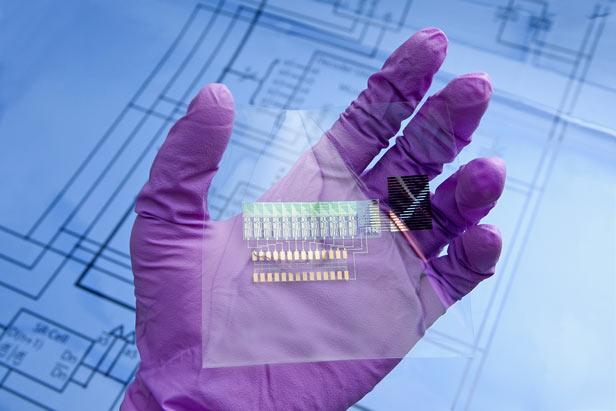

Last month, a small Norwegian company called Thinfilm Electronics and PARC, the storied Silicon Valley research lab, jointly showed off a technological first—a plastic film that combined both printed transistors and printed digital memory.

Such flexible electronics could be an important component of future products, such as food packaging that senses and record temperatures, shock-sensing helmets, as well as smart toys. But the story of how PARC’s technology—the printed transistors—wound up paired with memory technology from an obscure Norwegian company also provides a window onto a 10-year struggle by Xerox to transform the way it commercializes R&D ideas.

For most of its 40-year history, PARC (for Palo Alto Research Center) was as famous for squandering new technologies as it was for inventing them. The mouse, the graphical user interface, and the drop-down menu were all born at PARC—but it was Apple and Microsoft that commercialized them and made them cornerstone inventions of the PC industry.

The list of innovations lost hardly stops there. While Xerox did, of course, commercialize PARC’s blockbuster technology of laser printing, other PARC inventions ultimately commercialized elsewhere include Ethernet networking, the PDF file format, and electronic paper—created at the research lab in 1975, long before the Amazon Kindle and other e-books appeared.

By 2001, Xerox had seen enough. Facing poor financial results, its then-CEO, Anne M. Mulcahy, vowed to return the company to profitability. As part of that effort, Xerox reincorporated its cash-burning R&D center as an independent company, simply called PARC, with a mandate to turn a profit whether by licensing patents, through contract research, or by creating partnerships with other firms.

The buzzword attached to new era was “open innovation”; PARC’s researchers would now freely associate with the outside world to hone ideas and work out how to commercialize them. “When PARC spun out in 2002, open, collaborative innovation became, in essence, the business model for PARC,” says Lawrence Lee, currently PARC’s director of strategy. “But we’ve only figured out what that means in practice over the last couple of years.”

PARC’s advances in printing transistors came at around the same time the lab was being reorganized, making the technology a key proving ground for the new strategy. PARC at first hoped to develop organic electronic displays, a potentially huge market, but the technology proved difficult to manufacture, and it fell far short of silicon-based displays in performance.

In the old days, the idea might have languished. Xerox headquarters had often failed to embrace new inventions that didn’t relate to the company’s core businesses of selling copiers. But following the “open innovation” idea, PARC started shopping the technology to manufacturers, telling them that printed transistors could also provide very cheap, flexible sensors and computer logic for packaging, toys, and other uses.

Tamara St. Claire, PARC’s vice president for global business development, says manufacturers liked the idea but wanted to see what she terms a “minimum viable product”—management-speak for something more than a benchtop experiment. To develop one, in 2010 PARC formed a “co-innovation engagement” with Thinfilm, which was already making printed memory. The resulting prototype circuit was the first to combine both printed transistors and memory, according to PARC.

The Xerox company now has partnerships with several other firms and government agencies to use printed electronics in pressure-measuring helmets as well as in packaging that can sense pressure, sound, light, acceleration, or temperature. By doing so, it hopes to tap a market for printed electronics that an analyst firm, IDTechex, estimates could reach $45 billion by 2021.

For PARC, the partnerships are signs that open innovation is working. “There are plenty of great ideas at PARC, but you learn early on that execution is often the hard part—execution and timing,” says St. Claire. “It’s something you can say PARC is really starting to understand. You almost have to be as innovative in the commercialization—especially when you have game-changing technologies—as on the technology side.”

PARC, which once served only Xerox, now has an expanding list of technologies in development with outside partners that include Fujitsu, Motorola, NEC Display Solutions, Microsoft, Samsung, SolFocus, and Oracle. The change in strategy has helped turn it from a multimillion-dollar financial sinkhole into a modest, but growing, innovation business. In 2010, it was profitable on revenue of more than $60 million, a spokesman says. PARC, which has 250 employees, is also patenting at a fast clip, with about 150 patents filed per year since 2002.

The focus on doing business, not just having ideas, has also boosted morale, says Teresa Amabile, an organizational psychologist at Harvard Business School. “I’ve talked to a lot of scientists, technicians, and engineers doing R&D inside companies … and the people I talk to at PARC [are] more strongly, intrinsically motivated than the average,” she says. “They are driven by real passions and excitement for the disruptive discoveries they are making, coupled with excitement for seeing what they were doing actually being used in the world. That combination is pretty unusual.”