A Cloud over Ownership

Online services set content free from the physical world’s constraints—including those that have defined the very idea of possession.

Our possessions define us. Yet today the definition of possession itself is shifting, thanks to cloud services that store some things we hold dear on distant Internet servers. When those belongings reside in Netflix’s video service, Amazon’s Kindle bookstore, or Apple’s coming iCloud service, they become impossible to misplace, and easier to organize and access than before. They also gain new powers over us, and slip free of powers we once held over them—powers that have shaped our thinking and behavior for centuries. One consequence is to give the companies that provide cloud services tremendous amounts of unchecked control over these possessions. In some cases, that control has already been abused.

Despite the supposed revolution wrought by digitization, mass computing has until now left the fundamental nature of our possessions untouched. Collections of content have adorned the shelves and walls of our homes, schools, and courts since the Enlightenment. Nearly all of us (who are old enough) collected vinyl records in the 1970s, videotapes in the ’80s, CDs in the ’90s, and DVDs in the ’00s. Digitization simply morphed our urge to collect atoms into a thirst for curating bits, piled up on home computers.

In this age of streaming, however, possessing a personal content collection is a logical inconsistency. The 200 movies in my Netflix instant queue form an aspirational list, not a personal collection. Once I actually watch a movie, it disappears from the queue—the reverse of what happens on my shelf of DVDs. Personalizing a cloud-based collection of content is a pale imitation of what physical possession can offer. Even were I to show dinner guests my Amazon Kindle account, they wouldn’t gain the insight provided by a glance at a shelf in my dining room or the stack of books on my nightstand. There will never be a well-worn copy of my favorite digital book.

Dissolving physical possessions into the cloud is certainly convenient. It may even make us less covetous and more inclined to share. But this new form of property is also shaping up to have more serious consequences than the loss of a few conversations. One is that those previously inanimate possessions can now talk about you behind your back. Watch a movie on Netflix or Amazon, and the company’s servers know who you are and what you watch, when you watch it, where you’re watching from (more or less), and even when you fast-forward. U.S. law prohibits the release of movie titles that a person has watched, but cloud providers can do pretty much whatever they want with the other data they collect.

Today providers use this information to improve their service and make recommendations; tomorrow your data could travel to third parties. Apple could combine its own data with commercial data banks to tell Beyoncé the number of men aged 25 to 30 who are buying her tunes in New York City, for example; the music you place in Google’s cloud storage and playback service could shape the advertising that you see all over the Web.

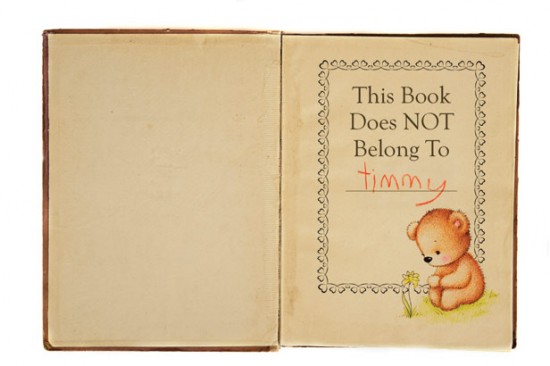

The tattletale nature of things in the cloud comes from the fact that unlike practically every other object on the planet, cloud-things remain unbreakably tethered to their producer. This tether means they bear little similarity to property as we have conceived it for hundreds of years. Popular understanding of what it means to own something—be it digital file or physical object—has up to now been well aligned with the law’s. When you buy a book you don’t get rights to the text, but you can read it, lend it to a friend, and then sell it to a secondhand shop, which can advertise it and sell it once more. But this tacit understanding of ownership is useless in the cloud.

Consider what happened in July 2009, when Amazon discovered it had accidently sold improperly licensed e-books of George Orwell’s 1984 and electronically obliterated them from every Kindle in existence. Winston Smith would have felt right at home, but the laws of physics, physical property, and copyright would have made such a maneuver triply impossible with a conventional book. Amazon could never have sent guards to conduct house-to-house searches.

In the cloud we are ruled by contract law and whatever constraints our provider builds into the long legal screeds we must agree to in order to use their services. Some aspects of these contracts are necessary for a company to operate. But they also provide an opportunity to place complex conditions on our possessions. Yes, you may lend Amazon e-books, but only for 14 days at a time. You may delete your e-books, but you can’t give them to a friend when you are done reading them. Publisher HarperCollins has decided that libraries may lend out e-books only 26 times before they must purchase a new copy. Other publishers prohibit lending entirely. Amazon’s Orwellian vanishing trick demonstrates that cloud providers have considerable power to enforce such rules. The nuclear option is the simplest restriction of all: terminating your account.

Back when you owned your own collection, you didn’t risk losing it because you had a billing dispute with the Book-of-the-Month Club, nor could a library fine threaten your family photos. Such scenarios are becoming possible as cloud services become more consolidated. Apple’s iCloud will look after e-mail, books, music, photos you take, and documents you create; Google’s cloud services span the same range and now also include a Facebook-like social network, Google+. A fight with a cloud provider that controls so many of your digital possessions is a daunting prospect.

Threats to a carefree cloud come from outside, too. A hacker might steal or delete all your files, perhaps with the help of a screw-up like one that for a short time allowed users to log in to Dropbox cloud storage accounts with incorrect passwords.

When the bits and atoms that make up your possessions are safely inside your house, the security measures that matter are the locks on your doors and windows, and your own competence. When that property is online, a laptop anywhere in the world can steal your stuff.

Despite such dangers, the cloud cannot and should not be stopped. We have much to gain from the freedom it offers. We want to be able to access “our” content or creations from anywhere—even if the possessions we access that way are not really ours after all. We want the peace of mind that comes from knowing that if our house burns down or is robbed, many of the real things that matter won’t be lost.

Yet not all the limits physical reality places on possessions are unfortunate. Many are pro-consumer and pro-freedom. Alas, those have been conveniently left behind by the largely unregulated market in which cloud providers operate. If we want the best of both cloud and physical possessions, we must find some way to rebalance the scales and reassert our rights.

Laws that force cloud providers to be humane landlords to those renting space on their servers, much as most U.S. states regulate landlords of physical space, would be a good place to start. Physical landlords can’t have a tenant’s possessions trucked off to the dump without due process; even those who withhold rent are given a chance to fight eviction in court. Cloud providers should similarly be prohibited from deleting your data at will, and there should be a legally mandated process for moving digital possessions to another cloud—or copying it to your home computer. Likewise, we need laws that force cloud providers to respect the privacy of their customers.

The industry currently has no incentive to allow us to negotiate our terms of service. When the laws of physics can no longer protect consumers and citizens as they have in the age of physical property, it is the obligation of society to intervene with the laws of man.

Simson L. Garfinkel is an author and researcher in Arlington, Virginia, who focuses on such topics as computer forensics and privacy.