Rewriting Life

Light Control

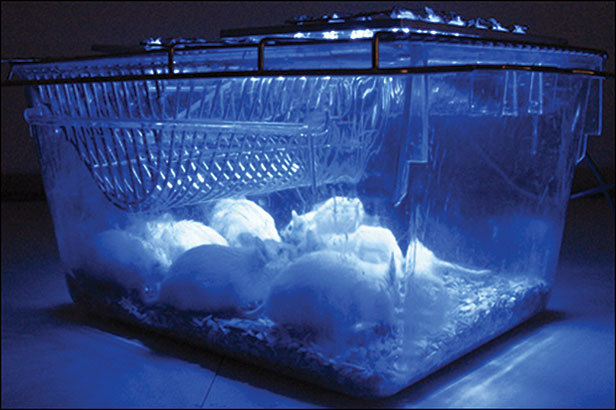

Scientists use light to direct gene expression in mice.

Source: “A synthetic optogenetic transcription device enhances blood-glucose homeostasis in mice”

Martin Fussenegger et al.

Science 332(6037): 1565-1568

Results: Researchers have developed a way to control gene expression with light. In cultured cells, the timing and intensity of light controlled both how much protein the target gene produced and when the production took place. When light-controlled cells were implanted in diabetic mice, researchers were able to manipulate the animals’ insulin levels.

Why it matters: Scientists now use chemicals to turn genes on and off, but light can be targeted more precisely. The technology could be used in research to study the role of different genes in development or other biological processes. By enabling precise control over protein production, it could also improve the manufacturing of drugs, such as some cancer therapies, that are made through biological processes rather than chemical synthesis. In the long term, cells engineered to carry the light-sensitive switch could be implanted into patients to produce a missing hormone, such as insulin, on demand.

Methods: Researchers engineered cells to carry the gene for melanopsin, a light-sensitive protein from the human retina, which causes a surge of calcium inside the cell when exposed to light. That calcium surge activates a protein that can be linked to any gene a researcher wants to manipulate. Shining light on the cells to trigger the calcium thus turns on the target gene.

Next Steps: The researchers plan to use the light-controlled system to produce protein-based drugs that have been difficult to make using traditional methods. They are also developing a light source that can be used inside a bioreactor, where the cells that produce proteins are grown.

Genome Editing

A new technique inserts genes at the right spot

Source: “In vivo genome editing restores haemostasis in a mouse model of haemophilia”

Michael Holmes, Katherine High, et al.

Nature 475: 217-221

Results: Researchers used a precise method of “editing” the genome to treat mice with hemophilia, replacing a defective gene with one that promotes blood clotting. After the treatment, the mice produced enough of the protein to speed clotting time.

Why it matters: Researchers hope the technology will help overcome a major problem with existing forms of gene therapy, which introduce a new gene at a random point in the genome. That can disrupt other genes, in some cases causing leukemia.

Methods: The technology relies on proteins known as zinc fingers, which bind to specific pieces of DNA to regulate nearby genes. By engineering different zinc fingers and attaching them to a gene-cutting enzyme, researchers have created tools that can snip the genome at a specific place and repair the target gene.

Next Steps: The technology will next be used in dogs, which are often used to test hemophilia treatments. Before the treatment can be tested in people, researchers need to make sure it is does not snip DNA in unintended locations.