` Elizabeth Mormino, 33

A telltale protein seen in people’s brains before they have Alzheimer’s could offer a clue about possible treatments.

Elizabeth Mormino knows it’s too late to save her grandfather, whose Alzheimer’s disease was diagnosed a few years ago. “It’s really hard to see a familiar face go through this, knowing that there’s really no drugs that work right now,” she says. But her work may help future patients by showing an intriguing new path to treating the disease.

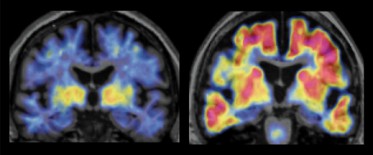

Mormino has figured out a way to combine two imaging technologies to detect the protein beta-amyloid, which is found in patients with Alzheimer’s, and has used them to look at the brains of people with no signs of cognitive decline. Although researchers have already been using one of the imaging technologies, called PIB-PET, to see beta-amyloid in the brains of living patients for a few years, Mormino is able to identify brain regions more accurately by combining PIB-PET and MRI data.

“I feel like we’re taking snapshots of people’s brains,” she says. “It feels very personal and intimate.”

The most surprising insight from her work is that some outwardly normal people are “walking around with a head full of amyloid, and oftentimes as much amyloid as somebody who actually has clinical Alzheimer’s disease,” she says.

How could this be? One hypothesis is that amyloid causes neurons to die, which then causes the clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s. So by the time patients have Alzheimer’s, anti-amyloid treatment is too late—the protein has already damaged too many brain cells. (Indeed, anti-amyloid drugs have not proved effective at treating Alzheimer’s.) But some of her healthy patients could have protective factors, whether in their genes or in their lifestyle, that allow them to tolerate high amyloid levels without developing Alzheimer’s.

Understanding such protective factors might “offer some insights into successful aging or the ability to remain resilient,” says Mormino. And there is a chance it could help specifically with Alzheimer’s prevention. To that end, researchers at the University of California, San Diego, and Massachusetts General Hospital, where Mormino is an assistant in neuroscience, have started clinical trials in which people who have high amyloid levels but no Alzheimer’s symptoms are getting anti-amyloid infusions to see if that staves off the disease.

The hope is that eventually Alzheimer’s could be prevented by regularly checking and treating amyloid levels, much the way heart attacks are averted by monitoring cholesterol.

—Anna Nowogrodzki