Proxima Centauri, 4.24 light-years away and the closest neighboring star to Earth, might have a second exoplanet in its orbit. Though not a confirmation of the planet’s existence, the new evidence, published in Science Advances, means Proxima b, a potentially habitable world, has a giant sibling.

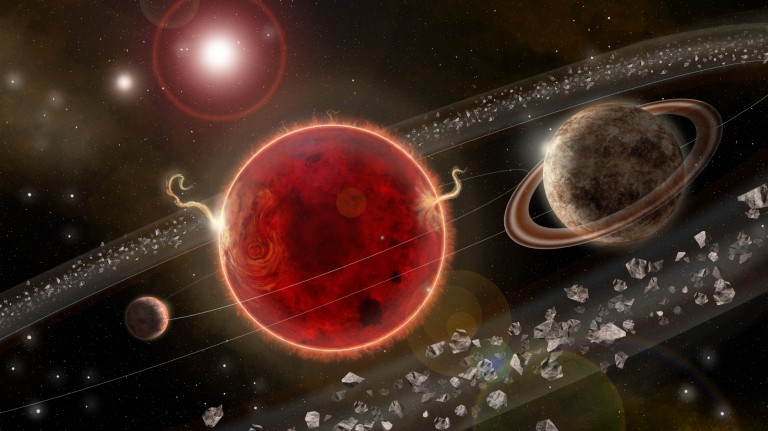

What’s it called? Proxima c, of course. We don’t know what its exact mass might be, but so far the evidence suggests it’s at least 5.8 times more massive than Earth. It could be a rocky “super-Earth” or a gaseous “mini-Neptune.” And it looks as if it orbits Proxima Centauri, a red dwarf star, every 5.2 years. It is almost definitely not habitable, and probably has temperatures of -233.15 °C.

Proxima b, discovered in 2016, is 1.3 times the mass of Earth. It is definitely rocky, and orbits its host star every 11.2 Earth days. It also resides within Proxima Centauri’s habitable zone (where conditions could be moderate enough for liquid water to potentially pool up on the surface). Of course, more recent observations of Proxima b suggest it is regularly blasted by solar flares and radiation, which would definitely render the planet uninhabitable.

How did we get this new evidence? Primarily by analyzing data gathered over 18 years by the European Southern Observatory’s HARPS and UVES instruments in Chile. They’re both spectrographs, which record light from another object and then split it into its component wavelengths for deeper study. Ultimately, the researchers noticed a periodic and persistent signal from this data, indicating there was likely some planet-size object orbiting Proxima Centauri.

Study coauthor Fabio Del Sordo from the University of Crete says before the study, there were no real signs before that Proxima c might exist. Many scientists had suspicions there could be another body orbiting Proxima Centauri, although most expected it would be something with a shorter orbital period. “In this sense our discovery was almost serendipitous,” he says.

How can we prove it’s real? The authors think the answer is the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, which astronomers are using to observe the position and velocities of one billion stars in the Milky Way. The mission goal is to use this data to map the galaxy in three dimensions.

The next sets of Gaia data are being released later this year and next year. Those latest measurements of Proxima Centauri should confirm whether the star’s movements agree with a potential second planet or not. Unlike direct imaging, the Gaia data wouldn’t necessarily confirm Proxima c’s existence but could disprove its existence outright.

Should we still be excited? For sure. Massive planets like this are usually thought to form near a star’s “snowline,” the point just far enough from a star to allow water to to freeze into ice. Proxima c, if it exists, resides way beyond the snowline, meaning either that it somehow formed inexplicably in the outskirts of the system, or the region of planet formation around Proxima Centauri used to be way hotter than we thought. Finding out what happened adds to our understanding for how planetary systems form. In addition, if Proxima c exists, astronomers will be keen on learning whether it affects Proxima b in any tangible ways.